It's a Duck, It's a Rooster, It's a … Dinosaur?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

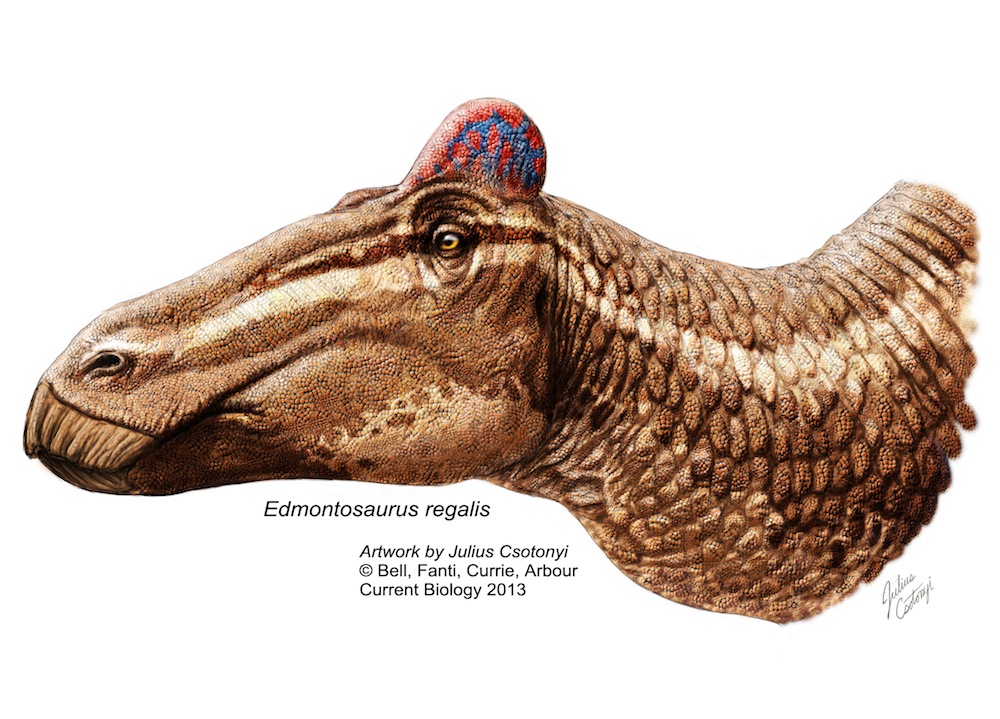

What has a mouth like a duck's and a comb like a rooster's? A dinosaur that roamed North America 75 million years ago.

A new fossil discovery reveals the duck-billed dinosaur Edmontosaurus regalis sported a fleshy comb on its head, similar to the ones on modern-day roosters. No such comb has ever been discovered before on a dinosaur.

"We're never short of being surprised by what these animals looked like," said study researcher Phil Bell, a paleontologist at the University of New England in Australia. [Paleo-Art: Colorful Images Bring Dinosaurs to Life]

Finding the fossil

Duck-billed dinosaurs, or hadrosaurs, were large herbivores that filled the same ecological niche as deer or kangaroo today. In the past century, paleontologists have discovered several hadrosaur fossils with skin impressions pressed into the rock around the bones. These "mummy" specimens, so dubbed because they reveal more than just bone, show that hadrosaurs had pebbly skin not unlike that of today's crocodiles and birds.

But skin impressions rarely preserve well around the skull, Bell said.

Bell's colleague, Federico Fanti, discovered the new E. regalis fossil in west central Alberta, about 45 miles (75 kilometers) from the town of Grande Prairie. They were surveying a well-known fossil site when Fanti noticed a string of vertebrae peeking out of a coffin-size boulder, Bell told LiveScience. The researchers had not found many bones still articulated in their original configurations, so they decided to collect the specimen.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Because the block was too big to move on its own, we used a rock saw in an attempt to trim it down," Bell said. "But no sooner did we start cutting into it than we found the first skin impression. We kind of had to bite the bullet and collect the whole block."

It was seven months before the team could get to the site with a truck and trailer, because the nearby Redwillow River was so high. But in 2011, the researchers drove a truck across the river, winched the boulder onto a trailer and brought it out of the field.

While Bell was preparing the fossil, he discovered something even more amazing than skin impressions.

"Having a good idea of the outline of the animal, I put my chisel into the rock, not expecting to hit anything, and lo and behold, I realized I'd put my chisel straight through the middle of some skin impressions that shouldn't have been there," he said.

Surprising skin

Bell had found a fleshy dome extending off of the duckbill's skull — something that had never been seen before. The dome included no bones and extended from the front of the eye sockets to the back of the head. It was almost 8 inches (20 centimeters) tall at its highest point and about 13 inches (33 cm) long.

"You can actually see the wrinkles in the skin that indicate that it had some flexibility to it," Bell said.

In modern birds, such combs are typically used for sexual display. They're found in both sexes in birds, so the presence of the comb tells researchers nothing about their dinosaur specimen's sex. The bones they do have belong to the neck and head, and don't reveal sex either.

"What we need to find now are additional specimens that show this structure, and perhaps by comparing their sizes or relative development, we might get an idea of their sex," Bell said.

It's not clear whether the comb is a feature only of E. regalis or if other duckbills might have had similar fleshy accessories. Skin associated with the head may not preserve well, meaning that other combs have vanished without a trace, Bell said. Or, they may have been overlooked. In the past, paleontologists considered skin impressions less interesting than bones, so they ignored them.

"People would actually remove and destroy the skin that's been preserved in order to get to the bones," Bell said.

Modern preparation has the potential to lead to a deeper understanding of dinosaurs, he said. "There's going to be no end of new and very surprising discoveries to come," Bell said.

The researchers report their findings today (Dec. 12) in the journal Current Biology.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus