Animal Sex: How Worms Do It

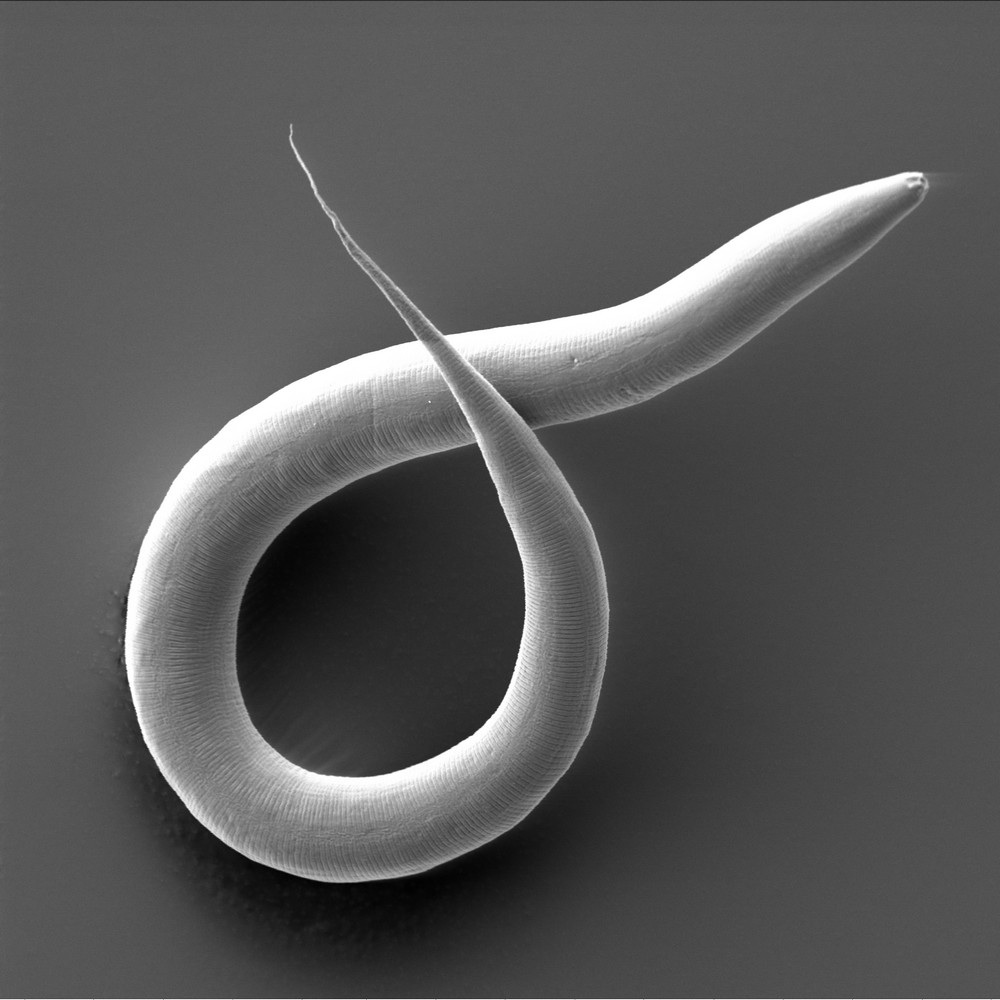

Though their serpentine locomotion might be off-putting to some, when roundworms do the deed, they're surprisingly graceful.

The roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans is a nematode that lives in temperate soil environments. A simple animal with only about 300 neurons, C. elegansis a common model organism in biology laboratories. But its reproductive system is quite complex.

Scott Emmons, a molecular geneticist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University in New York, studies the nervous system of C. elegans. While the worm's mating behavior could be described as a reflex, "this is not a blind machine," Emmons said.

The worm comes in two sexual forms: male and female-hermaphrodite. The hermaphrodite form has two X chromosomes, and it bears most of the organs of a typical female: ovaries, a uterus and a vulva. During her larval stage, she develops sperm first and then eggs, which are fertilized by the sperm in a structure called the spermatheca before making their way to the uterus. Hermaphrodite worms can produce about 300 offspring on their own, Emmons told LiveScience. [Top 10 Swingers of the Animal Kingdom]

Male worms, meanwhile, have only one X chromosome, and cannot reproduce without mating. So, they seek out lady hermaphrodites for a roll in the proverbial hay.

When a male finds a hermaphrodite, he presses his tail against her to stop her from moving forward. He slides backward along her body, feeling for her vulva with the sensory neurons around his genitals, or cloacal opening. Once he finds her lady bits, he stops backing up and extends hardened structures known as spicules, which he drums against her body, about seven times a second. He stops drumming once he inserts these spicules into the vulca, anchoring himself for the big performance. Finally, sensory neurons inside the spicules trigger ejaculation. [See Video of C. elegans Mating]

Getting the girl isn't always easy, even for the early worm. Young hermaphrodites resist mating, and males that aren't successful will eventually move on. L. Rene Garcia, a microbiologist at Texas A&M University, in College Station, has shown that the release of the nerve signal dopamine from sensory neurons tells the worm to give up on a mating attempt.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another group led by Cori Bargmann of The Rockefeller University, in New York, showed that tinkering with a chemical similar to vasopressin and oxytocin, which are involved in sexual intimacy in humans, took away the male worms' drive to mate.

Yet given that females can fertilize themselves, why did males evolve at all?

C. elegans feeds on bacteria that grow in decaying material in soil, which is a very spotty food source, Emmons said. Worms are more likely to be alone when they find food, so it's an advantage for them to be able to reproduce by themself. But hermaphrodites become inbred and accumulate harmful genetic mutations, so having males to mate with keeps the gene pool diverse. "In the nematode evolutionary tree, three species have this mating system, but they're not related," Emmons said.

After a hermaphrodite mates with a male, the resulting fertilized egg develops in utero. After about 40 cell divisions, the female lays about five or 10 eggs, one at a time. Half of the offspring will be male and half will be hermaphrodite. When a hermaphrodite reproduces on her own, all of her offspring will be hermaphrodites.

Males don't mate very efficiently, Emmons said, so after a few generations, the worms are mostly hermaphrodites. But there's a high occurrence of nondisjunction, in which one chromosome (the X, in this case) fails to separate when sex cells divide. This results in cells with only a single X chromosome, which develop into males.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.