New Wave Wi-Fi: Wireless Underwater Internet in the Works

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

There's Wi-Fi on the International Space Station, so why not at the bottom of the ocean? The problem: Radio waves, which carry wireless signals, are sluggish in water.

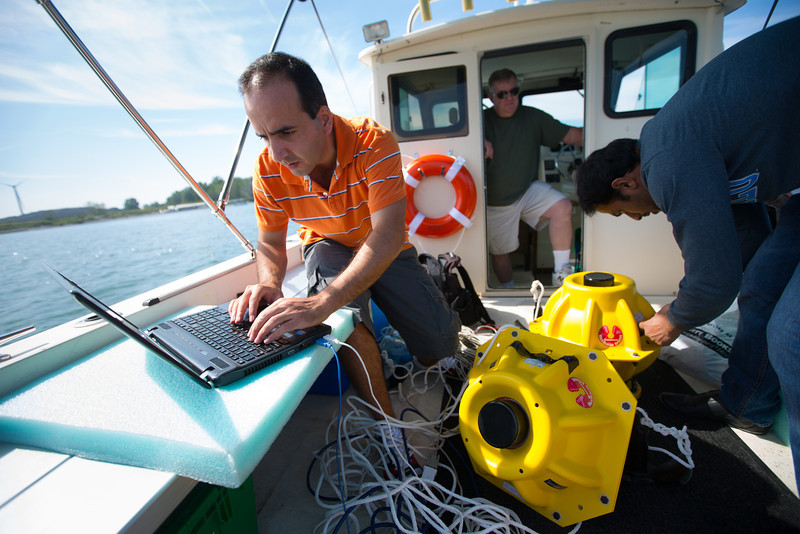

Now researchers from the University at Buffalo have a solution, and it's about to make the ocean a noisy place. Their wireless Internet prototype relies on sound waves.

The bulky underwater modems emit high-pitched chirps that can travel as far as about 0.6 miles (1 kilometer). The University at Buffalo team recently tested the system in Lake Erie, dropping two 40-pound (18 kilograms) sensors into the water and listening for chirps. The modems are as slow as dial-up phone systems from 30 years ago. However, the researchers hope one day a speedier wireless network could improve tsunami warning systems or help monitor oceans and climate.

The U.S. tsunami warning system currently relies on ocean-bottom sensors that send acoustic signals to surface buoys. The buoys transmit radio signals to a satellite, which alerts computers on land.

A seafloor wireless network could eliminate some of these communication steps, the researchers claim.

"A submerged wireless network will give us an unprecedented ability to collect and analyze data from our oceans in real-time," Tommaso Melodia, an electrical engineer at the University at Buffalo, said in a statement.

The team will present their latest results at the International Conference on Underwater Networks and Systems in Taiwan in November.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus