The Cold Sore Virus May Help Kids Fight Cancer (Op-Ed)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

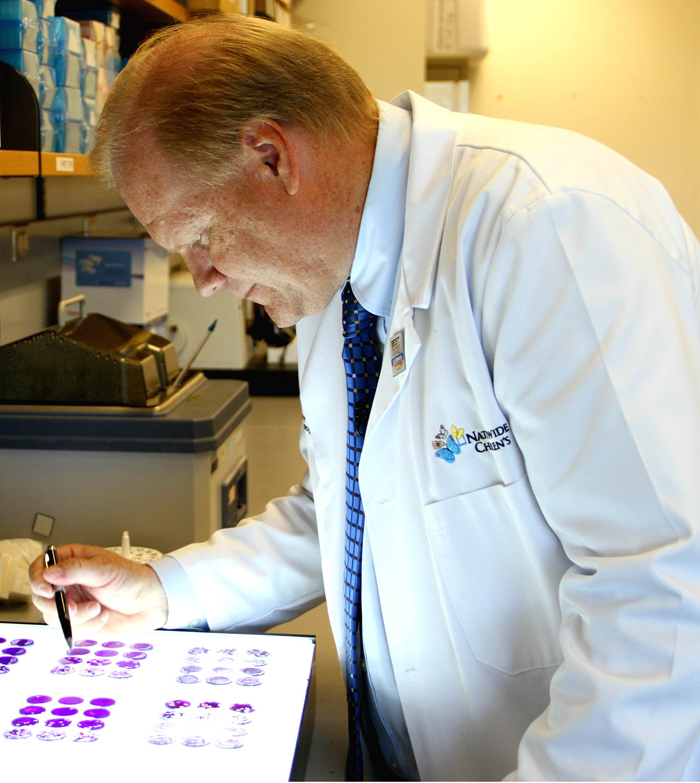

Dr. Timothy Cripe is a pediatric oncologist at Nationwide Children's Hospital. He contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Parents will go to great lengths to help their kids avoid viruses, but a new approach to battling childhood cancer is based on children getting a certain virus, not avoiding it. It's called viral therapy, and the idea is to take a virus that normally infects healthy tissue and alter it so it lodges inside of tumors, instead. The goal is to kill the tumors.

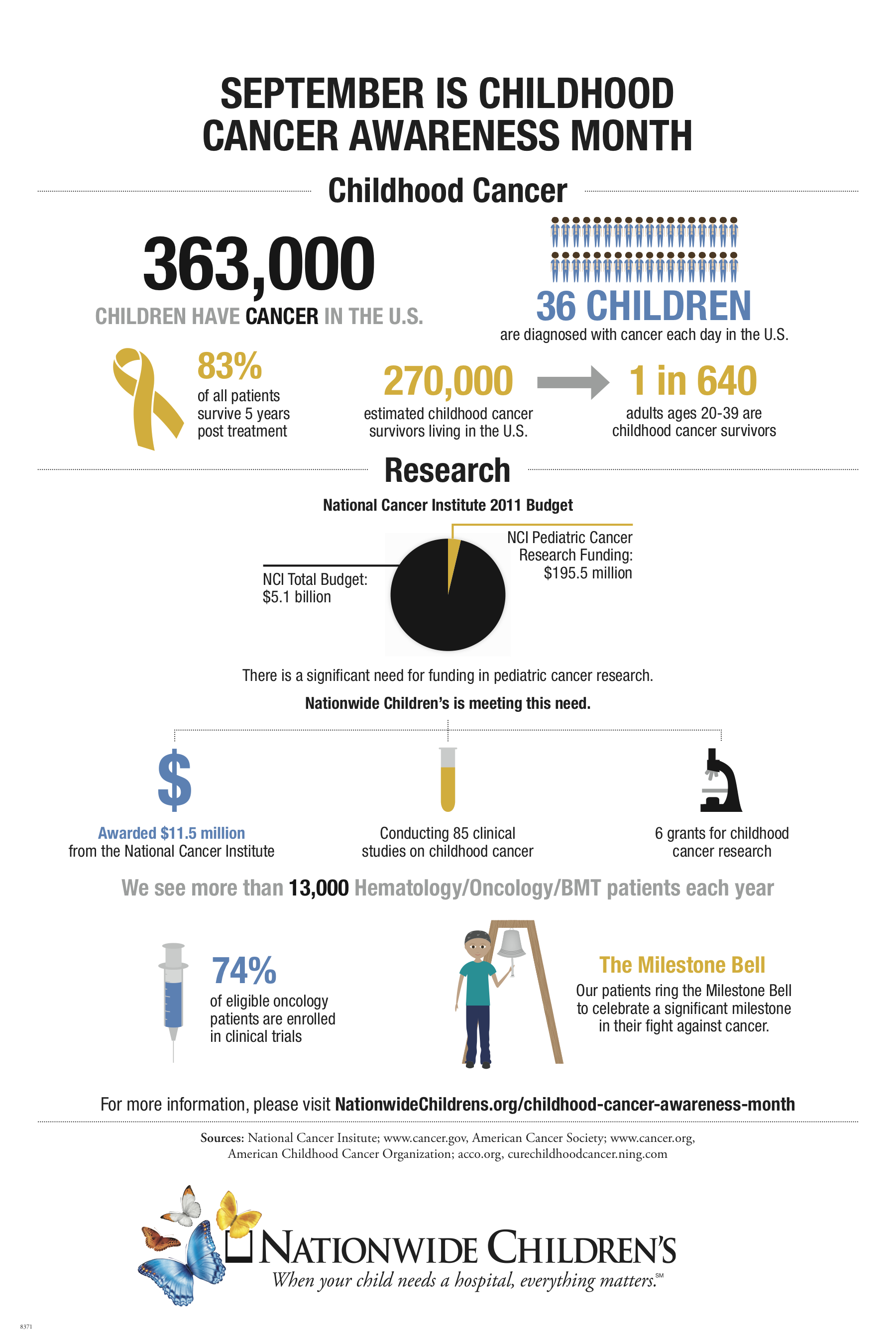

While viral therapy has been studied in adults, only a few institutions have studied it in kids. According to the American Cancer Society, almost twelve thousand children in the United States under the age of 15 will be diagnosed with cancer in 2013. As the chief of the Division of Hematology/Oncology and Bone Marrow Transplant at Nationwide Children's Hospital, I am determined to make a difference for those families.

When someone has cancer, cells in the infected part of the body start to grow out of control. Viral therapy, like other cancer treatments, is aimed at slowing and ultimately stopping the excessive growth of those abnormal cells.

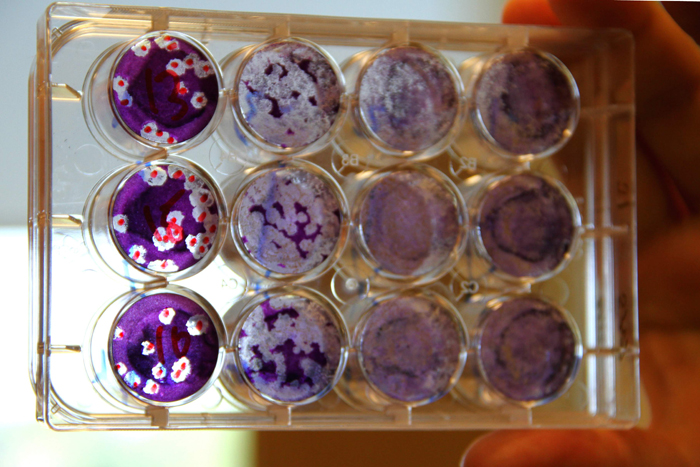

My colleagues and I use two types of viruses in our research. One type is a virus that has been crippled: weakened just enough so as not to cause any infection, but strong enough to infiltrate the tumor and direct the immune system to attack it. The other type includes genes that our research team has inserted in the lab, giving the viruses new properties. The genes are cancer-fighting genes, immune-stimulating genes and genes that attack cancer blood vessels. Most people would be familiar with one of the viruses we use, a version of the herpes simplex virus (HSV), otherwise known as the cold-sore virus. We slightly alter it in the laboratory, and then it is injected directly into a solid cancer tumor. This treatment has the potential to cause the tumor to shrink and disappear altogether.

Right now, we have studied this treatment in animals, and what we have found is that when we inject the animals with these viruses, the body fights the virus and concentrates on the tumors. The tumor cells are not recognized as foreign by the body's immune system. One of the effects we've found, and others have found as well, is that when we inject the tumor with a virus, it alerts the immune system to the presence of that tumor. So the virus, by virtue of it being an infection, causes a very inflammatory state. The viruses we use are engineered to be safe and utilize their cell-killing properties without causing infection.

If a child is already sick, the idea of introducing a virus might sound risky to some parents. But for the damage that the virus does to the tumor, it does not have any effect on the healthy tissue and cells throughout the body. That means there are very few, if any, side effects from the treatment.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Chemotherapy has been a tremendous tool for fighting pediatric cancer for decades, but the down side, of course, is all of the side effects. One of those side effects is suppressing the immune system. I do think the next generation of cancer therapies are going to be immune-based and will use viruses to alert the immune system to tumors.

Since cancer cells can spread throughout the body, we are also experimenting with a version of the altered virus that we can deliver intravenously. It could then travel through the body to find and kill cancer cells wherever they might be.

Viral therapy has the potential to make a world of difference for pediatric cancer patients who would otherwise be treated with chemotherapy. The hope is that patients would not have to experience the common side effects from chemo including hair loss, fatigue, nausea and weight loss or gain.

There are some side effects to viral therapy that researchers have observed, but those effects are mainly short lived. They are the kinds of things you might expect from getting an infection: fever, chills, aches. There's really no one that I'm aware of in the world who has been injected with one of these viruses to help with attack cancer and had any serious adverse events.

My team and I are launching a phase I clinical trial which will study the safety of viral therapy for solid cancer tumors in kids, and opening up the possibility of other trials that will determine if the approach works either alone or in combination with other therapies. We will be looking at this treatment for cancers such as neuroblastoma and sarcoma.

Cancer is rarely, if ever, cured with a single type of therapy. It's going to be important for researchers to understand what other therapies we can combine with these viruses to maximize their effect. Right now, we have done our research in animals, but we are confident in our results so far and think that this could make a difference.

We hope by using this form of biological warfare to win the battle against cancer we can not only improve the quality of life for kids fighting cancer but that we can ultimately save lives.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus