Sci-Fi Gives 'Fuzzy' Prediction of Future, Says Kim Stanley Robinson

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

"Science fiction is any idea that occurs in the head and doesn't exist yet, but soon will, and will change everything for everybody, and nothing will ever be the same again," sci-fi author Ray Bradbury once said. "It is always the art of the possible, never the impossible."

Indeed, science fiction does seem to possess an uncanny ability to predict the future. Jules Verne foretold rocket ships and submarines, H.G. Wells predicted the atomic bomb, and Arthur C. Clarke gave humanity satellites and online newspapers. But not all science fiction is prophetic.

"All sci-fi put together gives you a feel for the future that is fuzzy," said contemporary sci-fi author Kim Stanley Robinson, author of the "Mars" trilogy and most recently "Shaman" (Orbit, 2013). The futures are not always compatible, but "taken together, they give you a kind of weather forecast," Robinson said.

Science fiction can be divided into different categories depending on how far in the future the stories take place, Robinson told LiveScience. [Science Fact or Fiction? The Plausibility of 10 Sci-Fi Concepts]

"Near-future" sci-fi encompasses stories set in the very near future, perhaps the day after tomorrow. This type of sci-fi represents an extension of the present. The writings of authors William Gibson and Neal Stephenson fall into this category. Robinson called near-future science fiction "the best current realism," as it tends to follow a dystopian character, taking the problems of today to their most extreme conclusions. Near-future sci-fi "will seem prescient in some ways, and off in others," Robinson said.

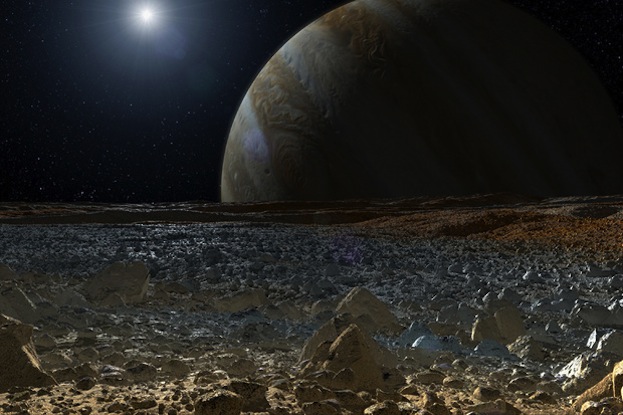

Then there's "space opera," which is set in the distant future, hundreds to millions of years from now. Humans are often portrayed as having explored the galaxy, as in the "Star Trek" TV series and films. In contrast with near fiction, space opera has a utopian feel, because the problems of surviving Earth have been solved, Robinson said. "There's a magical quality to it," he said, but the question then becomes, "How do you keep [that] culture going?"

Between near-future sci-fi and space opera lies a zone Robinson calls "future history." These stories are far enough in the future that they don't resemble the present, but not so far that they seem magical. They're often set at a specific date, and allude to the history that led up to that time. Much of sci-fi falls into this category, including works by Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov and Robinson himself, such as the "Mars" trilogy, his most well-known work, and his book "2312."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Of the three types of sci-fi, near-future science fiction gives perhaps the most realistic view of the future, because it is grounded in the present. Near fiction often explores the dark side of new technologies or social constructs, but their dystopian visions of the future may be less faithful prediction than they are plot device.

"Protagonists in a dramatic situation, adventures, hard times, revolution, resistance, struggle" — these elements all make for a good story, Robinson said. But fiction about utopias can also be interesting, he said, citing Ursula K. Le Guin's novel "The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia" and his own novel "Pacific Edge." Even in a utopia, there can still be death and lost love, Robinson said. "Basic human dramas will never go away," he said.

Most sci-fi about the future focuses on scientific and technical developments, assuming that government and social systems will remain the same. The absence of political or economic sci-fi is a shame, Robinson said. "There is a radical, political economy wing in sci-fi, but there's so little of it that it doesn’t have an influence on the general public," he said.

Still, a few writers have left a mark on politics. Wells, for example, wrote about technocracies where rationality won out. After World War II, when the United Nations was reconstructing the international order, "they were working on Wellsian premises," Robinson said.

Sci-fi is often just as much a commentary on the present as it is on the future. "It's a way of talking about right now, as well as looking at the future," Robinson said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus