Snail Gets Spots to Fool Predators

A freshwater snail common in ponds across Europe can adjust its pigmentation in response to certain environmental stressors, new research suggests.

Radix balthica, spanning less than a half-inch (0.8 centimeters) in length, sports dark body pigmentation that is visible through its translucent yellow shell. Individuals vary in skin pattern, with some speckled with dark spots and others covered in a more uniformly dark pattern.

Researchers have thought the snail's variable coloring was genetically predetermined, and didn't change during the snail's life. But new research from a team at Lund University in Sweden has shown that the presence of predators and the intensity of damaging UV radiation from the sun do, indeed, influence their color coats. [Amazing Mollusks: Images of Strange & Slimy Snails]

"[Previous studies] tried to use these patterns to distinguish between populations, but what we found was the snails from the same pond can look very different," said study researcher Johan Ahlgren. "One single snail can express all of these different morphs."

Physically morphing in response to environmental cues — a trait called phenotypic plasticity because the physical expression of an organism's genes is called its phenotype — occurs within many plants and animals, and has even been shown within R. balthica for other traits, such as shell shape. However, pigmentation plasticity, or changeability, had not yet been shown in this species, the researchers say.

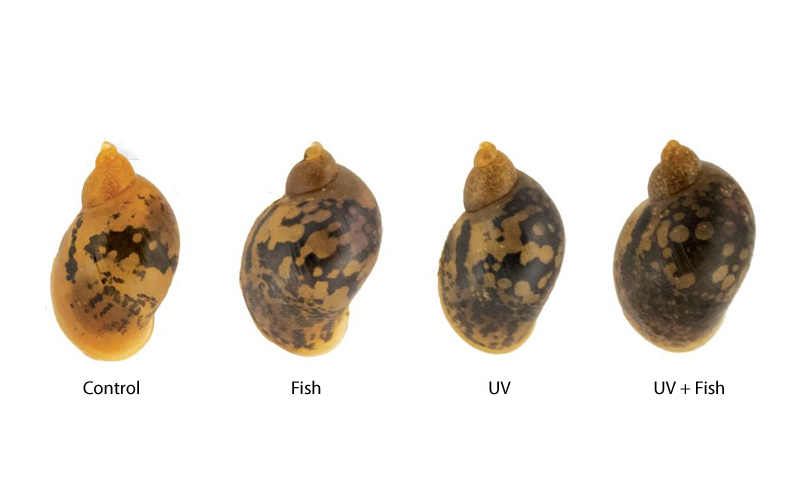

To determine how different environmental cues affect the snail's skin pattern, the team tested a random sampling of newly hatched snails under four conditions, including exposure to chemical cues of a predatory fish, exposure to UV light, exposure to both a predatory cue and UV light, and a control with neither environmental stressor.

The team measured the snails' pigmentation after eight weeks under these conditions. They found predatory cues induced spotted patterns, which would provide camouflage against a pebbly pond floor, whereas any exposure to UV radiation — with or without the predatory cue — induced a darker, less complex pigmentation that likely protects the snail from the damaging effects of radiation. The finding suggests protection against radiation takes precedence over protection against predators.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Whether the snails morph multiple times during a lifetime remains unclear, but the team hopes to address this question in future research, Ahlgren said.

The findings are not entirely unexpected, said Anurag Agrawal, an ecology and evolutionary biology researcher at Cornell University who was not involved in the study, since many animals show similar phenotypic plasticity. Still, this case adds one more valuable example for biologists to consider how such plasticity can vary across the animal kingdom.

"One thing that is interesting about the study is that there are two very divergent environmental cues that influence the same phenotype," Agrawal said. "I think that's a nice contribution. When we have different environmental cues that pull [an organism] in two directions, how does the organism decide which [phenotype] it is going to utilize? Those are important questions."

The findings are detailed today (Sept. 17) in the journal Biology Letters.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow LiveScience on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus