A massive marine lizard may have swum like a shark, new research suggests.

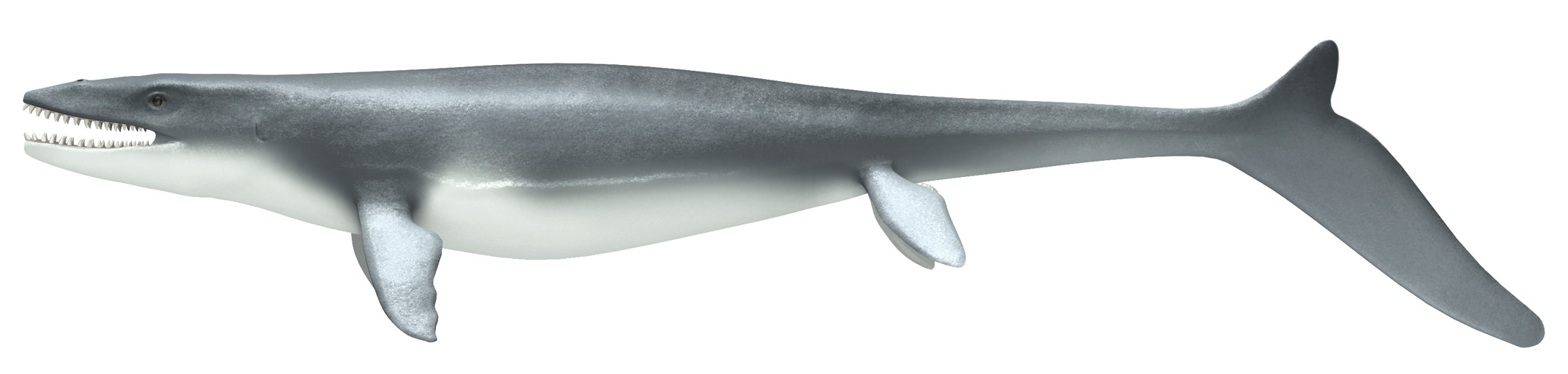

The top predators of the oceans during the late Cretaceous Era, mosasaurs, had skeletons that resembled lizards, but streamlined bodies and tail fins that resembled sharks, according to a study published today (Sept. 10) in the journal Nature Communications.

The findings suggest creatures relied on just a few types of bodies to swim quickly and easily through the deep oceans, and they evolved to have such body features because they're the most efficient from a physics perspective, said study co-author Johan Lindgren, a paleontologist at Lund University in Sweden. [See Images of Mosasaurs, the Sharklike Lizards]

Ancient sea lizards

Around 98 million years ago, sea levels were vastly higher than they are today, leaving many shallow pools — which would today be dips in the land — for creatures to inhabit. Land-dwelling lizards called mosasaurs soon expanded into these niches.

The massive lizards, which could grow to 49 feet (15 meters) long, gradually evolved more adaptations to the deep oceans and became the top predators, similar to killer whales today, Lindgren said. Mosasaurs disappeared about 66 million years ago, in the extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Lindgren had suspected for several years that some of the youngest species of mosasaurs had fins like sharks, but none of the skeletons contained imprints of soft tissue to confirm that hypothesis.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Preserved tissue

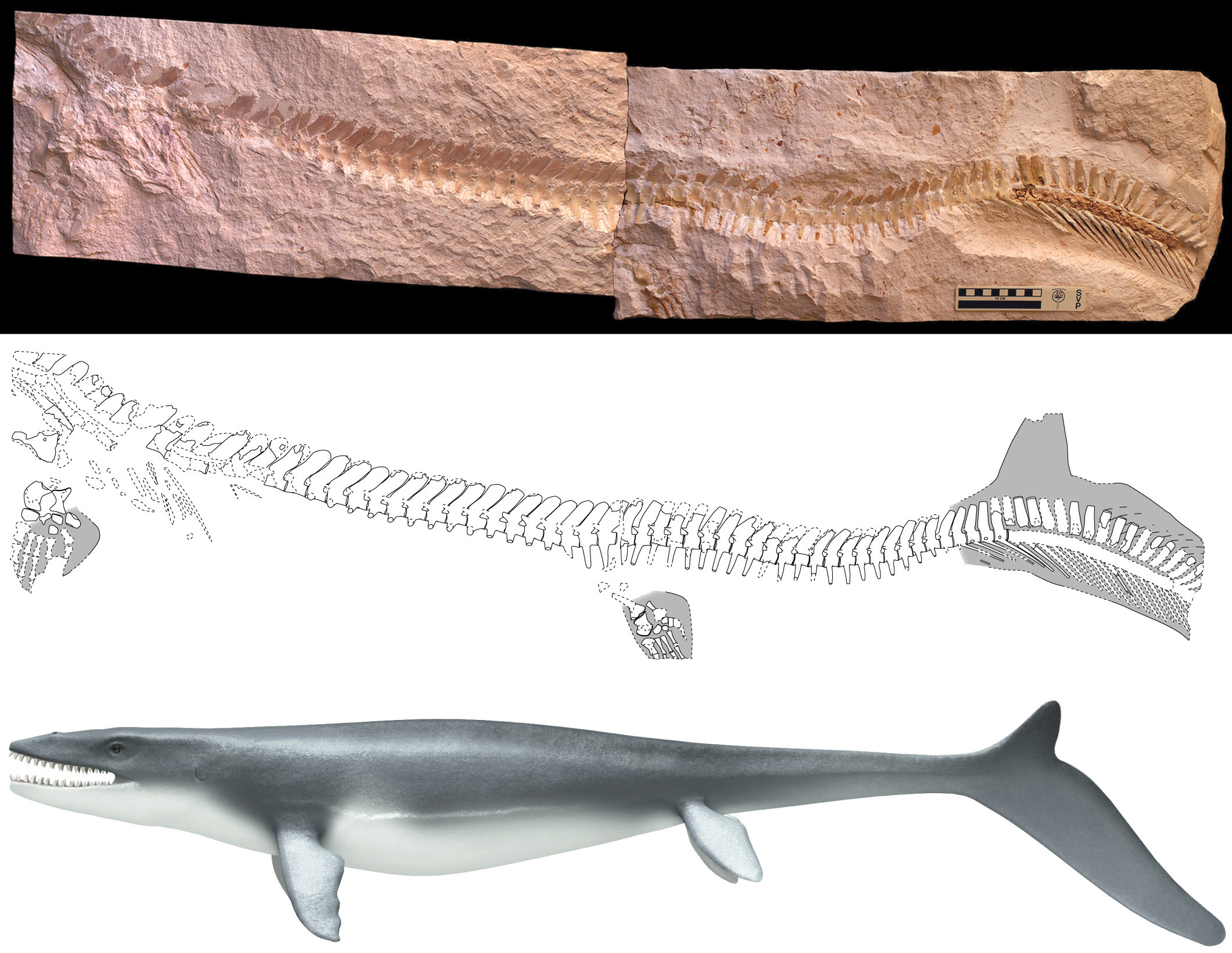

However, in 2008, Lindgren and his colleagues discovered a juvenile mosasaur, just 6.5 feet (2 m) long, in sediments in Jordan that dated to about 70 million years ago.

The specimen, a Prognathodon known as Tenerasaurus hashimi, had the well-preserved imprint of the back and tail fins, which looked like the tail of a shark, only flipped upside down.

The specimen shows convergent evolution in action, Lindgren said. (Convergent evolution occurs when unrelated organisms develop similar adaptations to contend with similar selective pressures, such as swimming efficiently in the ocean.)

"In order to become an efficient open ocean swimmer, you need to have a streamlined body in order to have a minimum amount of resistance," Lindgren told LiveScience.

So whales, sharks and ichthyosaurs all evolved similar body plans, because these body shapes reduced drag, or water resistance, Lindgren said.

This study convincingly and unequivocally shows that the youngest of these monsters of the sea swam like sharks, said Takuya Konishi, a paleontologist at the University of Alberta, who was not involved in the study.

"This is almost the final product, if you like, of a mosasaur lineage, which lasted for about 32 million years," Konishi told LiveScience.

The earliest versions of these sea creatures probably swam like eels, with their entire bodies undulating in the water, but by about 88 million years ago, they developed flippers. Sometime in the next 20 million years, the sea monsters evolved their sharklike tail fins, he said.

Now, scientists should "start looking for other mosasaurs between 66 [million] and 98 million years ago and see how rapidly those fins evolved," Konishi said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.