Ancient Rodentlike Creature Once Dominated Earth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

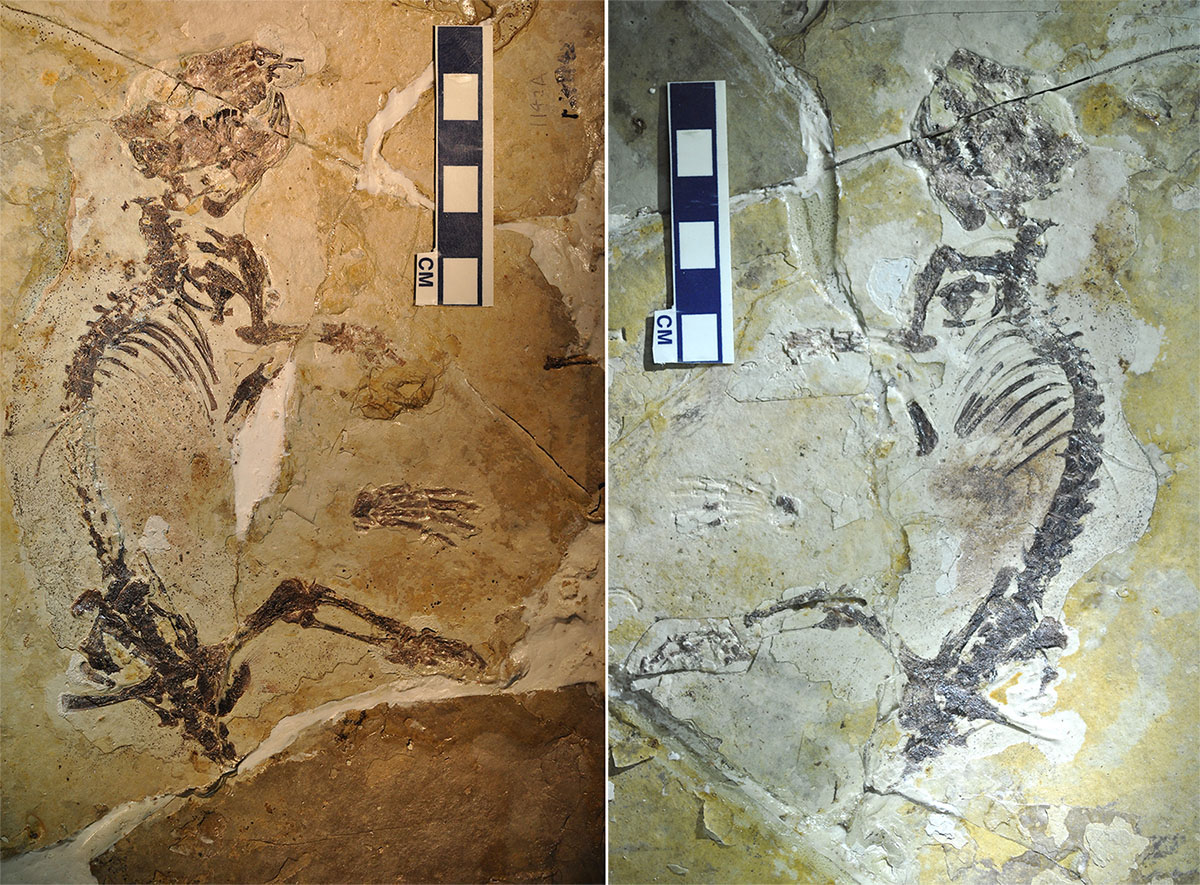

A fossil of a chipmunklike animal discovered in China is now helping reveal how this group of mammals reigned as long as the dinosaurs did, researchers say.

A group of mammals known as the multituberculates flourished across the planet from about 170 million to 35 million years ago, a span of 135 million years. This is about as long as dinosaurs were the dominant species on Earth.

Much like today's rodents, multituberculates occupied an extremely diverse range of habitats, such as below the ground, on the ground and in trees. [See Photos of Newfound Creature & Other Ancient Mammals]

"Some could jump, some could burrow, others could climb trees and many more lived on the ground," said researcher Zhe-Xi Luo, a paleontologist at the University of Chicago.

By the end of their time, these creatures — the most abundant mammalian lineage in the fossil record — had evolved complex teeth that allowed them to enjoy vegetarian diets, as well as treetop-climbing abilities. Both of these adaptations helped the animals to become dominant among their contemporaries.

"Paleontologists are always interested in how certain superabundant, superdiverse groups of animals got started," Luo told LiveScience.

Now, Luo and his colleagues have revealed a new 160-million-year-old chipmunklike fossil that represents the earliest known multituberculate skeleton. This oldest ancestor on the multituberculate family tree, now named Rugosodon eurasiaticus, apparently possessed many of the adaptations that subsequent multituberculate species came to rely on, helping to set the stage for the group's dominance.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For instance, multituberculates that lived 100 million years or more after R. eurasiaticus and were capable of tree climbing and jumping "had the most interesting ankle bones, capable of 'hyper-back-rotation' of the hind feet." Luo said. "What is surprising about this discovery is that these ankle features were already present in Rugosodon — a land-dwelling mammal."

R. eurasiaticushad relatively short, thick fingers, like those typically found on creatures that lived mostly on the ground. However, its highly flexible ankles suggest it could at least occasionally scamper up trees.

"If you look at squirrels, you see similar adaptations," Luo said.

In addition, R. eurasiaticus had wrinkled teeth ornamented with ridges, pits and grooves that would have enabled it to eat many different types of food, including both animals and plants. These teeth would have allowed later multituberculates to diversify from an animal-dominated diet to a plant-dominated one.

"A modern rodent species that had very similar ornaments on its teeth, the African dormouse, are seedeaters that also eat some fruit as well as worms, arthropods [creatures such as insects and crustaceans] and so forth — the perfect omnivore," Luo said.

The wrinkled teeth and flexible ankles that R. eurasiaticus possessed suggest adaptations that arose very early in the evolutionof multituberculates helped pave the way for later members of the order (a scientific classification of organisms that includes families of genuses). Judging by other fossils discovered near the location where the R. eurasiaticusfossil was found, the multituberculate apparently lived in a temperate area rich in plants by the shores of shallow lakes. The animals could have fed on the seeds and leaves of ferns and cycads, or perhaps fished out clamlike creatures known as conchostracans from the water for food, Luo said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Aug. 16 issue of the journal Science.

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus