Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Long-necked dinosaurs such as Diplodocus probably had less-flexible necks than previously thought, new research suggests.

For the study, published Wednesday (Aug. 14) in the journal PLOS ONE, researchers analyzed the movements of ostrich necks in order to gain insight into how long-necked dinosaurs may have moved.

The results suggest the long-necked beasts probably didn't swivel their heads around, or move their necks from ground to treetop, as scientists had previously proposed.

Faulty model

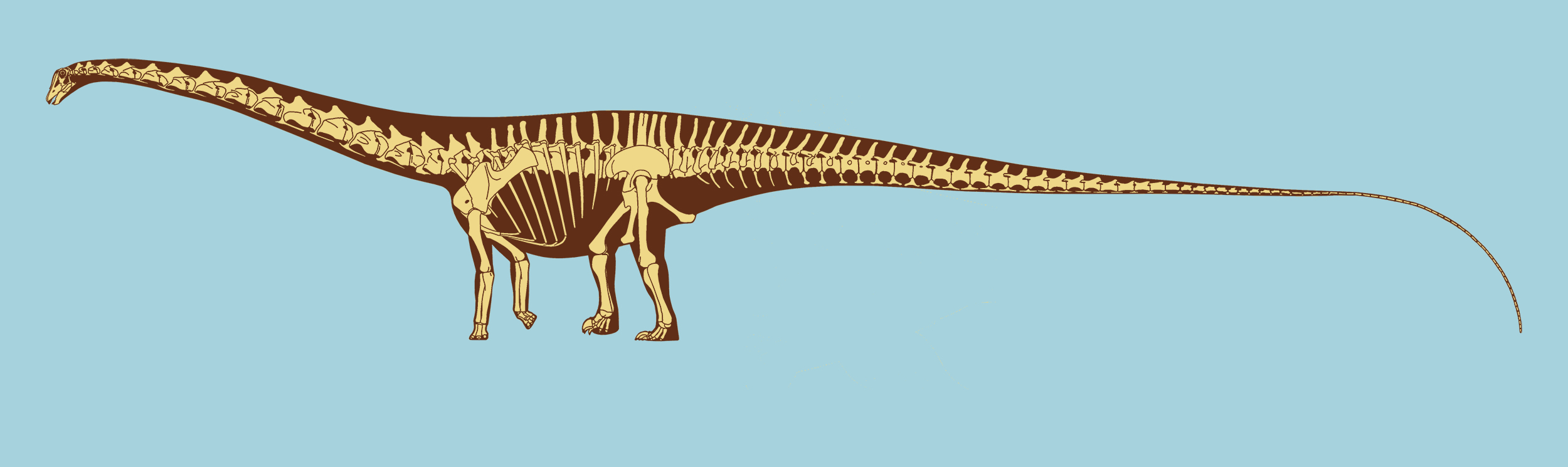

Ever since sauropods, or long-necked dinosaurs such as Diplodocus and Apatosaurus were first discovered, people debated why these majestic beasts had such long necks. The massive creatures — the biggest ever to walk the Earth — had absurdly long necks that could grow up to 50 feet (15 meters) long. Some scientists believed the vegetarian dinosaurs nibbled plants that grew on the ground, whereas others thought the beasts grazed on trees. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

Past researchers had come up with computer models based just on these dinosaurs' vertebrae and concluded that the giant dinosaurs had fairly flexible necks, said study co-author Matthew Cobley, a paleontologist at the University of Utah. That would have allowed the dinosaurs to swivel their necks to eat everything in sight before having to move their bodies — an energy-saving measure for such massive beasts.

But Cobley and his colleagues weren't convinced.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team looked at the most similar living animal with an extremely long neck: the ostrich. They analyzed the cartilage and soft tissue in the ostrich necks and found that these tissues reduced the overall flexibility of the neck.

"Imagine two bones next to each other moving. If you put anything in between them, like a muscle or something, then it's going to reduce the motion between those two bones," Cobley said. (Past models hadn't accounted for any tissue between the neck vertebrae.)

Stiff-necked creatures

The findings suggest that sauropods probably didn't swivel their heads around to nibble every branch bare or move their heads from treetop to the ground. Rather, they probably had to move their large, lumbering bodies a fair amount to access the 880 lbs. (400 kilograms) of food they ate daily.

The new study, "is a huge step forward, and it's going to inspire more work in the future," said Matthew Wedel, a paleontologist at the Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, Calif., who was not involved in the study.

But the ostrich may not be a perfect analogy to the long-necked beasts: Ostriches walk on two legs, whereas sauropods walk on four, Wedel added. Ostriches' heads bobble a bit as they walk, but that may not be the case for the dinosaurs.

"Somebody probably needs to go do the same thing with a giraffe," which is four-legged, Wedel told LiveScience.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus