Global Warming Makes Sea Less Salty

You won't want to drink water straight from the ocean anytime soon. But the salt content is on the decline, a sign of potentially worrisome consequences that scientists can't accurately predict.

Since the late 1960s, much of the North Atlantic Ocean has become less salty, in part due to increases in fresh water runoff induced by global warming, scientists say. Now for the first time researchers have quantified this fresh water influx, allowing them to predict the long-term effects on a "conveyor belt" of ocean currents.

Climate changes in the Northern Hemisphere have melted glaciers and brought more rain, dumping more fresh water into the oceans, according to the analysis.

One of the expected high-profile consequences is a rising sea that will swamp coastal communities. But there are other possible effects.

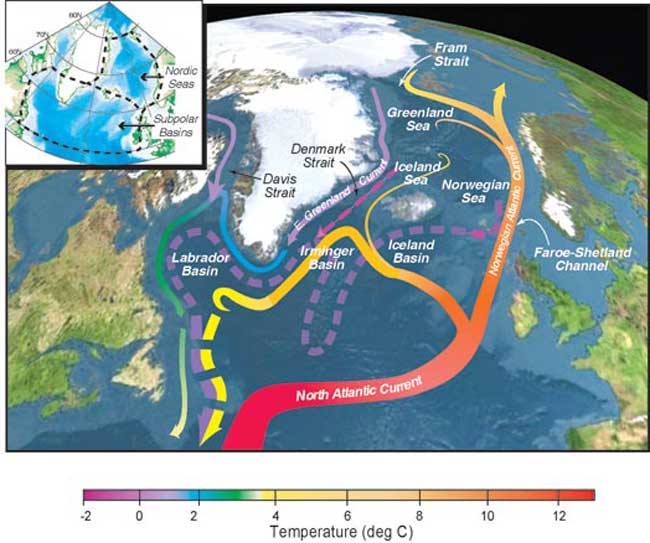

"Precipitation and river runoff at high latitudes have been increasing," said Ruth Curry of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). "In the last decade, fresh water has been accumulating in the Nordic Seas layer (the upper 1,000 meters) that is critical to the ocean conveyor, so it is something to watch."

What's going on

Curry and Cecilie Mauritzen of the Norwegian Meteorological Institute calculated that an extra 19,000 cubic kilometers of water flowed into and diluted the northern seas between 1965 and 1995.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For comparison, the Mississippi River releases about 500 cubic kilometers of freshwater into the Gulf of Mexico each year, while the Amazon, the Earth's largest river, discharges roughly 5,000 cubic kilometers annually.

Because water with lower salinity is less dense, adding fresh water may affect ocean flows like the conveyor belt – a system of Atlantic currents that exchanges cold water in the Arctic region for warm water from the tropics.

The top part of this conveyor is made of warm ocean currents, like the Gulf Stream, flowing northward along the surface. At high latitudes, this water cools and sinks – releasing its heat to the atmosphere and making for moderate winter climates in places like England.

Deep, cold currents return some of the water to the south.

Slight changes in the currents -- both seasonal and longer-term variations -- affect everything from hurricane formation to droughts and heat waves.

Future uncertain

No significant change in the conveyor belt has yet been observed, however. Curry and Mauritzen estimate that it would take another century to slow the ocean exchanges if the current rate of fresh water inflow continues.

Scientists disagree over whether the planet is warming and how much humans might be contributing. But most climate experts see a clear warming trend that they expect will continue for at least a century.

"Given the projected 21st Century rise in greenhouse gas concentrations and increased fresh water input to the high-latitude ocean, we cannot rule out a significant slowing of the Atlantic conveyor in the next 100 years," Curry said.

She emphasized, however, that effects will be gradual. "We are not suggesting that the Gulf Stream will shut down," she said.

A study last year concluded that an altered conveyor belt could actually plunge the planet into a global cooling event.

The new research was published in the June 17 issue of the journal Science.

Related Stories