'Monster Star' Baby Photos Captured by Giant Telescope

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

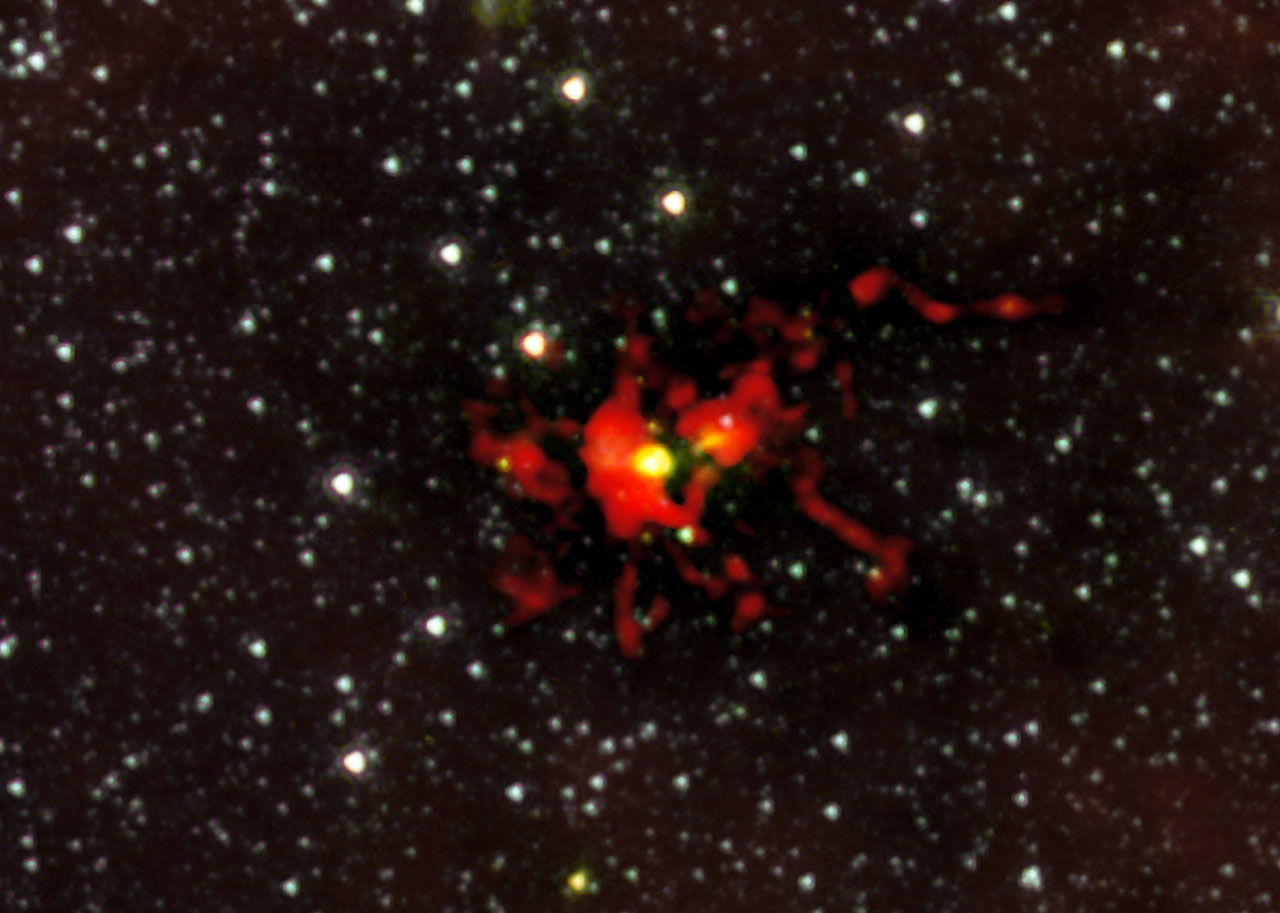

A giant radio telescope in Chile has captured amazing baby photos of what will eventually be a colossal star 11,000 light-years from Earth. Even more shocking: It's still growing, scientists say.

The giant star, which scientists billed as a "monster star," is forming inside a vast cloud of interstellar dust that has 500 times the mass of the sun. It was discovered by astronomers using the huge Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter array telescope, or ALMA, in Chile's high Atacama Desert.

"The embryonic star within the cloud is hungrily feeding on material that is racing inwards," officials with European Southern Observatory, a partner in the ALMA telescope, explained in an announcement today (July 10). "The cloud is expected to give birth to a very brilliant star with up to 100 times the mass of the sun."

The details of the process of star formation are murky, and the new observations could help scientists understand how stars like this one come to be. One leading theory suggests large clouds of gas collapse inward, with the material at the center eventually forming one or more stars. Another theory, however, posits that large clouds first break up into smaller clouds that each give rise to smaller cores that form stars.

The new results strongly support the first, global collapse theory, rather than the fragmentation theory, researchers said.

"The ALMA observations reveal the spectacular details of the motions of the filamentary network of dust and gas, and show that a huge amount of gas is flowing into a central compact region," team member Ana Duarte Cabral from the Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Bordeaux in France said in a statement.

The huge star in the process of forming is just one of numerous stars being birthed by the massive cloud, the scientists said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The remarkable observations from ALMA allowed us to get the first really in-depth look at what was going on within this cloud," research leader Nicolas Peretto of CEA/AIM Paris-Saclay in France, and Cardiff University in the U.K., said in a statement. "We wanted to see how monster stars form and grow, and we certainly achieved our aim! One of the sources we have found is an absolute giant — the largest protostellar core ever spotted in the Milky Way."

The cloud in the new study is called the Spitzer Dark Cloud (SDC) 335.579-0.292. The largest star expected to result there, with about 100 times the sun's mass, will be a very rare object: Only about one in ten thousand Milky Way stars become so large.

"Not only are these stars rare, but their birth is extremely rapid and their childhood is short, so finding such a massive object so early in its evolution is a spectacular result," team member Gary Fuller of the University of Manchester in the U.K. said in a statement.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Managing editor Tariq Malik contributed to this report. Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus