Earthquake Creep Is Shallower Than Thought

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

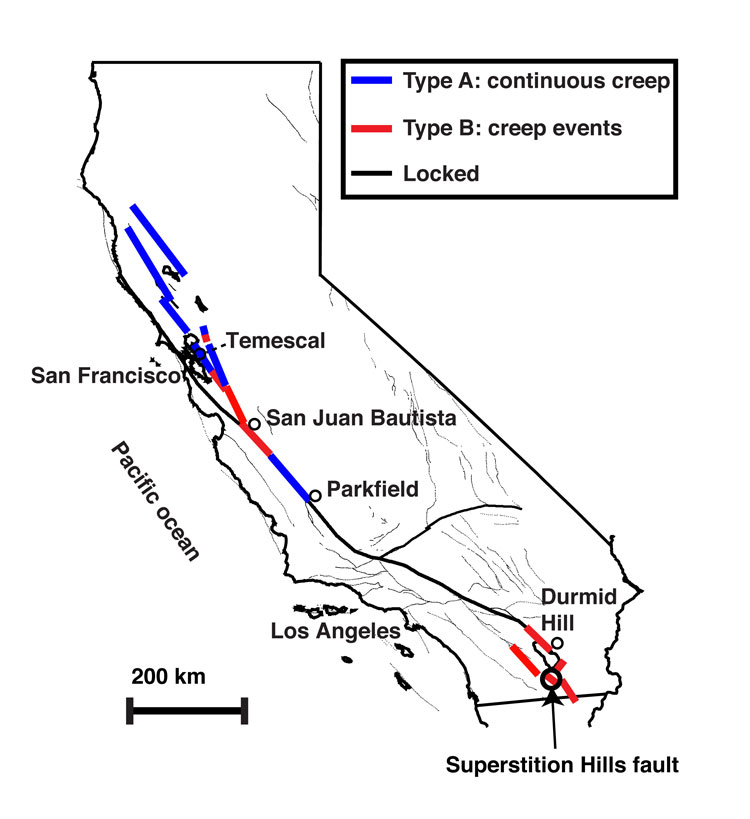

Along the San Andreas Fault between San Juan Bautista and Parkfield in central California, scientists issue no dire warnings of future bridge-collapsing earthquakes. This section of the 800-mile-long (1,300 kilometers) fault produces no strong earthquakes at all.

Instead of sticking and locking together and breaking in occasional big temblors, the fault creeps, steadily releasing strain through thousands of tiny microquakes. One of the big puzzles in geology is understanding why faults like the San Andreas creep, and how the process links to large earthquakes elsewhere on the fault.

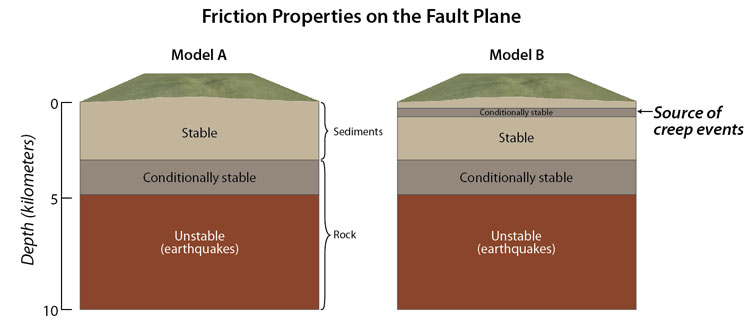

A new computer model finds that creep starts shallowly — about 3,200 feet (1 km) below Earth's surface — on strike-slip faults such as the San Andreas Fault. Earlier models — based, in part, on rock lab studies — had suggested the creeping zone was deeper, between 1.8 to 3 miles deep (3 to 5 km).

Instead of using rocks in the lab, the new model relied on real-world earthquake and fault-creep data collected after the 1987 Superstition Hills earthquake in Southern California. The Superstition Hills Fault is a strike-slip fault in the Imperial Valley, near El Centro. The results of the new model were published June 2 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

The model requires a new, "conditionally unstable" zone in the sediments at the top of the fault. No regular earthquakes can strike in this zone, but the fault can slowly crawl. In the San Andreas Fault's San Juan Bautista creeping section, this zone is about 985 feet (300 m) thick, according to the model. On the Superstition Hills Fault, the zone is about 3,200 feet (1 km) thick. But both creeping zones are at the same depth, around 3,200 feet (1 km) below the surface.

The researchers said the results are an important step in ground-truthing mechanical fault models."Creep is a basic feature of how faults work that we now understand better," Jeff McGuire, study co-author and a researcher at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, said in a statement.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus