A Blast of a Find: 12 New Alaskan Volcanoes

In Alaska, scores of volcanoes and strange lava flows have escaped scrutiny for decades, shrouded by lush forests and hidden under bobbing coastlines.

In the past three years, 12 new volcanoes have been discovered in Southeast Alaska, and 25 known volcanic vents and lava flows re-evaluated, thanks to dogged work by geologists with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the U.S. Forest Service. Sprinkled across hundreds of islands and fjords, most of the volcanic piles are tiny cones compared to the super-duper stratovolcanoes that parade off to the west, in the Aleutian Range.

But the Southeast's volcanoes are in a class by themselves, the researchers found. A chemical signature in the lava flows links them to a massive volcanic field in Canada. Unusual patterns in the lava also point to eruptions under, over and alongside glaciers, which could help scientists pinpoint the size of Alaska's mountain glaciers during past climate swings.

"It's giving us this serendipitous window on the history of climate in Southeast Alaska for the last 1 million years," said Susan Karl, a research geologist with the USGS in Anchorage and the project's leader. [Image Gallery: Alaska's New Volcanoes]

Volcano forensics

The project kicked off in 2009 as part of an interdisciplinary effort to better understand volcanism in Southeast Alaska, Karl said.

The team's first result, from a volcanic pile about 40 miles (70 kilometers) south of Mount Edgecumbe, was an intriguing match in time to the panhandle's biggest volcano. The team planned to test if the two were related, sort of a geologic genetic test. But even though the two volcanoes had erupted at about the same time in the past, their chemistry was wildly different. It was like one volcano was a freshwater fish and the other came from the salty ocean. And what really captured the geologist's attention were signs that the little volcano squeezed out lava that oozed next to glaciers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That's when we realized we had a whole new kind of volcano separate from Mount Edgecumbe," Karl told OurAmazingPlanet.

Lava chemistry holds forensic clues that reveal what was happening in Earth's crust and mantle when the magma formed. The unusual chemistry sent Karl and her collaborators hunting for more rocks to test. This meant days-long backpacking trips into remote wilderness or submersible dives to underwater volcanoes.

Not only did they find the same unique chemical signature at other sites, the team stumbled upon new volcanoes overlooked by earlier mappers.

"We're convinced now there's probably a whole bunch of green knobs out there covered with timber that may be vents that may have never been mapped," said James Baichtal, a geologist with the U.S. Forest Service based in Thorne Bay, Alaska, and a project leader.

Connection to Canada

Now comes the CSI twist. All of these newly tested lavas in Alaska are kissing cousins to volcanoes in Canada, such as Mount Edziza, which last erupted about 10,000 years ago.

The connection makes perfect sense, Karl said. "I'm actually surprised no one has hypothesized it before," she said. "It made total sense that this volcanic province would extend across Southeast Alaska, and now I have the data to show that's the case."

Little known outside of Canada, Mount Edziza is part of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province, a broad swath of volcanoes and hot springs some 1,250 miles (2,000 km) long and about 375 miles (600 km) wide.

Karl's big picture meets approval with scientists studying Canada's volcanoes.

"I knew there were volcanics to the west in Alaska, but I didn't know they were nearly [this] extensive," said Ben Edwards, a volcanologist at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, who is not involved in the project but has visited the new volcanoes with Karl and Baichtal. "They have really found a lot more places than we realized, but there's certainly no reason for them not to be there. It makes a lot of sense."

As in Canada's volcanic province, Southeast Alaska's volcanoes and hot springs line up as amazingly linear features. Here's why: The tortured history of this corner of North America, a legacy of collision between the North America and Pacific tectonic plates, created a meshwork of leaky faults and fractures. Magma escapes from Earth's mantle through this patchwork when forces pull on the crust, opening space. The matching chemistry also hints that magma in both regions comes from a similar mantle source.

"It's always fun to discover a new vent; it's fun to find a fossil, and then to be able to understand why it's there is always very satisfying," Karl said. "That's what makes scientists tick."

Strange new finds

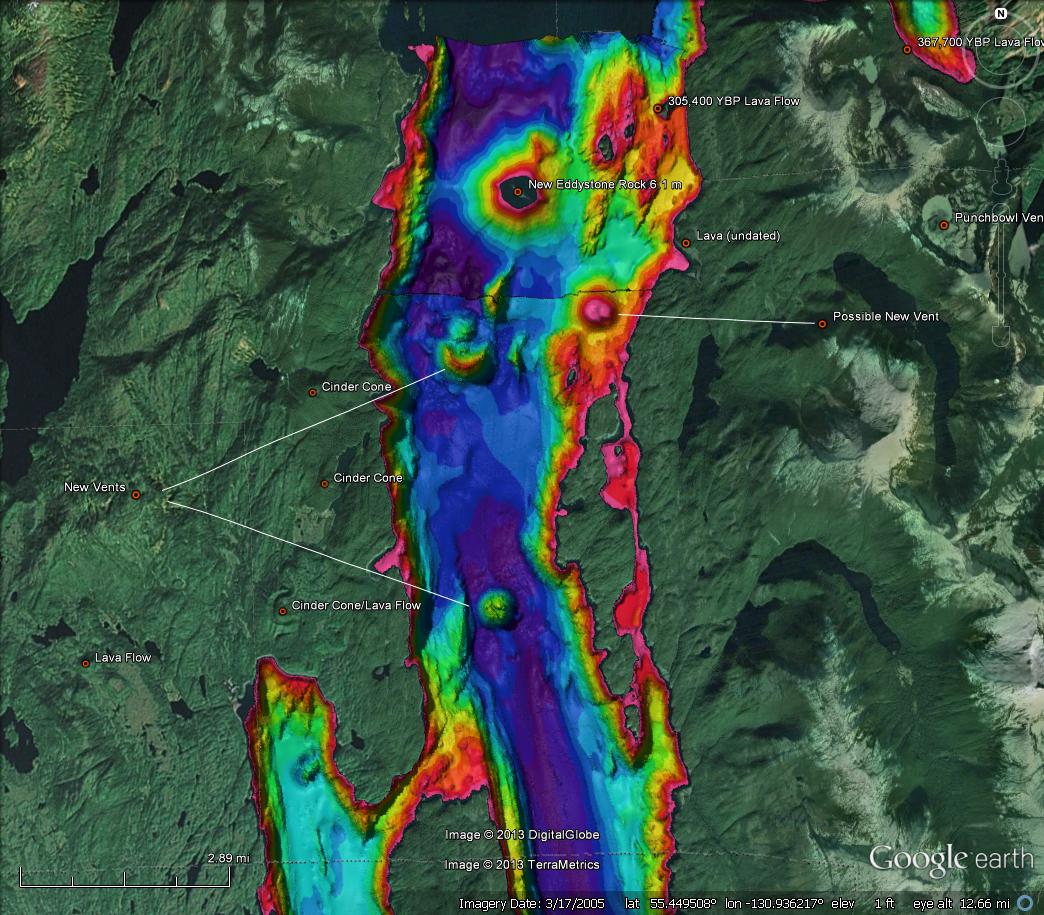

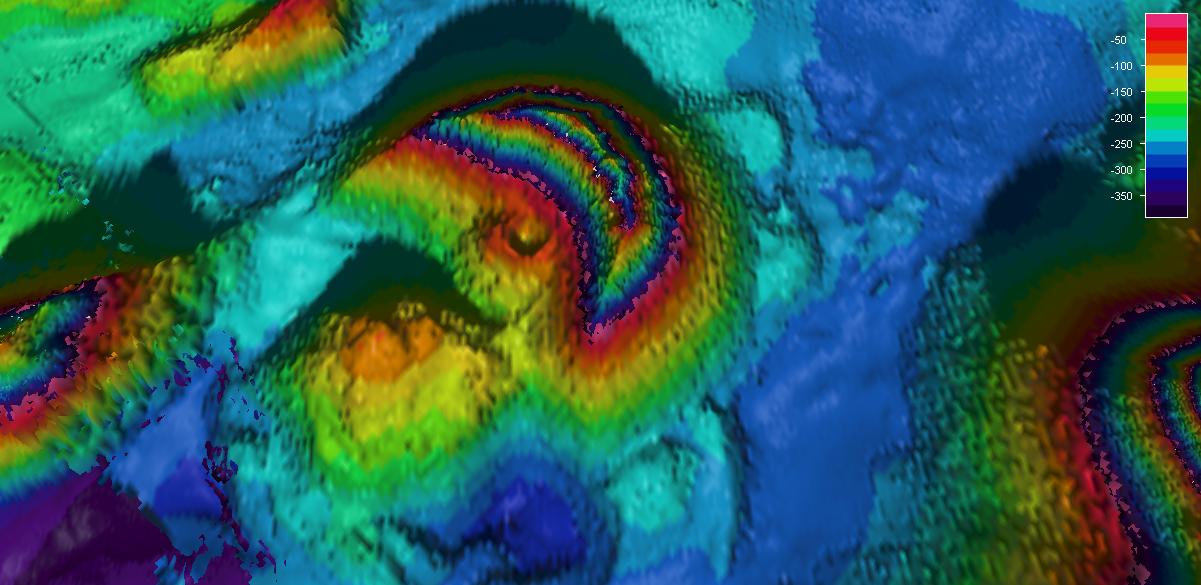

Some of the unusual finds Karl and Baichtal have uncovered include a maar lying 295 feet (90 meters) underwater near Cape Addington, about 40 miles (65 km) west of Craig, Alaska. Maars are bomblike craters blasted out when magma rising underground hits groundwater and explodes. The maar is about 13,800 years old, Baichtal said. Sea level was 394 feet (120 m) lower when the maar formed.

The latest find is an underwater volcano in Behm Canal, where hundreds of thousands of tourists on cruise ships have sailed by New Eddystone Rock, an eroded volcano. Behm Canal is dotted with cinder cones, both onshore and below the water.

East of Ketchikan, a basalt flow lapped onto a 42,000-year-old beach, preserving shells, pinecones, pine needles and pollen. Barnacle plates sitting on top of the lava are about 13,000 years old, Baichtal said. The whole package now sits about 260 feet (80 meters) above sea level, hinting at how much Earth's crust has bobbed up since the last ice age.

"It gave us how much isostatic rebound there is today. That's one of those really great days in geology. You couldn't have written a better script, and there's a lot of those kind of things coming out of there," Baichtal said.

Volcanoes and climate change

While the volcanoes in Canada and Alaska have erupted for more than 10 million years, emerging data suggests that the last 3 million years of glaciers growing and retreating in Alaska and British Columbia also prompted many small volcanoes to erupt, because the changing ice mass flexed the Earth. This activated the fractures and made room for more magma to rise.

In Tolay Regional Park, north of Mount Edziza, Edwards is assembling evidence of periodic eruption pulses in the last 2.5 million years.

"We don't have a lot of the information yet, but it's consistent with some sort of link between glaciations and volcanism. If you put 2 to 3 km [1.2 to 1.8 miles] of ice on that part of the cordillera and then remove it pretty quickly, it may facilitate extension," he said.

The molten rock also has preserved impressions of bygone glaciers. Many of the lava flows touched ice, leaving a distinctive cooling pattern in the chilled rock. By dating the glacially cooled lava flows, researchers such as Karl, Baichtal and Edwards hope to better understand how much land mountain glaciers covered during past glaciations. About one-third of global sea level rise could come from melting mountain glaciers, but estimating their past size is difficult because growing glaciers plow through evidence of their predecessors.

Risk of eruptions

Despite its great size, the overall risk from eruptions in the Alaska portion of the volcanic province is low, Karl said.

In Canada, the volume of erupted lava is less than 240 cubic miles (1,000 cubic km) every million years in the last 2 million years. By comparison, Hawaii's Kilauea volcano spewed 4,650 cubic miles (19,400 cubic km) in the past 300,000 to 600,000 years. [Big Blasts: History's 10 Most Destructive Volcanoes]

The most recent eruption in both countries was at the Blue River lava flow in Lava Fork, which crossed the Alaska-Canada border 120 years ago, according to new dating work by Karl and her colleagues.

"Even though, theoretically, a volcano that erupted 120 years ago is an active volcano, but because it's so remote there isn't any real concern about it," Karl said.

However, an eruption in 1775 killed a village of First Nations people in Canada, though scientists aren't sure why. Lava didn't reach the town, and some researchers suspect gas from the volcano may have suffocated residents.

Karl notes that an earthquake on the Fairweather Fault, a major offshore strike-slip fault, presents a greater risk than a volcanic eruption. "If something is rumbling and bubbling we have so much more technology to become aware of it before it's a hazard, We can't predict exactly when the Fairweather Fault is going to go, and that's a much larger hazard," she said.

With 15,000 miles of shoreline and hundreds and hundreds of islands to explore, Karl and Baichtal think there are more volcanoes to discover in Southeast Alaska.

"It's a tough place to get around, but Sue and I just laugh at it. We will never finish," Baichtal said.

Editor's note: This story was updated June 3 to correct the volume of erupted lava in Canada.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus