Fighting to Save an Endangered Bird — With Vomit

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A psychological warfare program centered on vomit could help save the marbled murrelet, an endangered seabird that nests in California's old-growth redwood forests.

The robin-sized murrelet lives at sea but lays one pointy, blue-green egg each year on the flat, mossy branch of a redwood. While breeding, its back feathers morph from black to mottled brown to better match the forest. For two months, both parents race back and forth to the coast as far as 50 miles (80 kilometers) each day at speeds of up to 98 mph (158 km/h) while evading peregrine falcon and hawk attacks. After the chick hatches, it pecks off its redwood-colored down and, flying solo, launches straight for the ocean. Penguins have nothing on the murrelet.

"They're a seabird like a puffin, and they have this crazy lifestyle that's like a living link between the old-growth redwood forests and the Pacific Ocean," said Keith Bensen, a biologist at Redwood National Park. "It's strange to have an animal with webbed feet in the forest," he said.

Despite its amazing skills, the marbled-murrelet population is down by more than 90 percent from its 19th-century numbers in California, thanks to logging, fishing and pollution. Murrelets live as far north as Alaska, but the central California population is most at risk. Yet even though the state's remaining old-growth redwood trees are now protected, the murrelets continue to disappear.

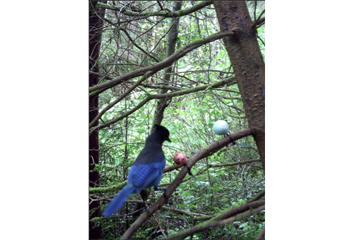

The culprit: the egg-sucking, chick-eating Steller's jay.

About 4,000 murrelets remain in California, with about 300 to 600 in central California's Santa Cruz Mountains. Squirrels, ravens and owls also swipe murrelet eggs, but jays are the biggest thieves in California, gobbling up 80 percent of each year's brood. Unless more eggs survive, the central California population will go extinct within a century, according to a 2010 study published in the journal Biological Conservation.

To boost California's murrelet numbers, biologists in California's Redwood National and State Parks are fighting back against Steller's jays and their human enablers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The art of avian war

With cash earmarked for murrelets from offshore-oil-spill restoration funds, the parks have the rare ability to fund research studies and restore habitat. The two-pronged approach will teach the black-crested jays to avoid murrelet eggs on pain of puking. More importantly, it will shrink the jay population by thwarting access to their primary food source — human trash and food. [Image Gallery: Saving the Rare Marbled Murrelet]

"Every time folks throw out crumbs to bring out jays and squirrels, it's having a real impact on a very rare bird nesting overhead in an old-growth redwood tree," Bensen told OurAmazingPlanet.

A Western bird, the blue and black Steller's jays like to frequent cleared forest edges — which are filled with bugs and berry bushes — and campgrounds littered with tasty trash and crumbs. As humans spend more time in the forest, the jay's numbers are booming. Their density in campgrounds is nine times higher than in other forest areas, said Portia Halbert, an environmental scientist with the California State Parks.

"We see this crazy overlap of jays in campgrounds because of the density of food," Halbert told OurAmazingPlanet. The overpopulation also menaces federally protected species, such as snowy plovers, desert tortoises and California least terns — the jays eat their eggs too.

Steller's jays don't seek out murrelet eggs. But when the birds circle picnic areas near murrelet nests, some discover the chicken-size eggs make a fine treat. The smart, savvy birds will return to the same spot over and over, searching for food. Murrelets, to their misfortune, nest in the same tree every year.

Masters of disguise, the first marbled murrelet nest wasn't discovered by scientists until 1974, in Big Basin Redwoods State Park. The seabird doesn't actually build a nest, instead choosing a flat branch covered in cozy moss and needles, with cover to hide from airborne predators. At dawn and dusk, parents switch roles, flying offshore to dive for fish and invertebrates. [Watch the mysterious marbled murrelet]

"For an animal that lives for some 20 years, losing an egg is a terrible, terrible loss," Bensen said. "They're investing an enormous amount of energy into that one baby."

Killing Steller's jays won't help the murrelets; even more of the marauding birds will invade campgrounds to compete for vacant territory, biologists have concluded. Plus, jays are part of the natural ecosystem, said Richard Golightly, a biologist at Humboldt State University in California. Instead, researchers think aversion training is the cheapest, most effective way to stop Steller's jays from snacking on murrelets.

"It freaks everybody out to train wild animals to do what you want, but it surprised the heck out of all of us how much more feasible it was than we thought," Bensen said.

World's worst Easter egg hunt

The plan, the brainchild of Humboldt State graduate student Pia Gabriel, centers on carbachol, an odorless, tasteless chemical that provokes vomiting with just a small swallow. Researchers fine-tuned the correct dose with lab tests at Humboldt State in 2009. Small chicken eggs, dyed blue-green and speckled with brown paint, were offered as meals to jays, with carbachol hidden inside. Wild Steller's jays in this first treatment group usually tried just one taste of the carbachol-filled fake eggs.

"All of a sudden, their wings will droop, and they throw up. That's exactly what you want — a rapid response — so within five minutes, they barf up whatever they ate," Bensen said. The quick action helps the jays link the eggs with the illness.

Some jays wouldn't even touch the eggs — evidence that murrelet egg-nabbing is a learned behavior, Golightly said.

In spring 2010 and spring 2011, a team zip-tied hundreds of the copycat eggs to redwood-tree branches in several parks. Each chicken egg was painstakingly colored (Benjamin Moore Oceanfront 660) and speckled to resemble murrelet eggs. A control batch of red speckled eggs also decorated the forest.

"We've been accused of being the Easter bunny in the woods," Golightly told OurAmazingPlanet.

A second wave of eggs set out a few weeks later measured whether wild jays learned to avoid tossing their lunch. The mimic eggs reduced egg-snatching by anywhere from 37 percent to more than 70 percent, depending on where the eggs were deployed. For instance, one spot lost eggs to bears, so not as many jays got to sample the carbachol. (The bogus eggs were set low on branches, to avoid drawing jays toward real murrelet eggs.)

A retched success

The tests were so successful that Halbert applied for oil-spill restoration funds to start training Steller's jays in the state parks. In spring 2012, during murrelet nesting season, researchers spread hundreds of vomit-inducing eggs throughout Butano State Park and Portola Redwoods Park in the Santa Cruz Mountains. This year, the project included Memorial Park, a county park with old-growth redwoods. [Nature's Giants: Tallest Trees on Earth]

"It's worked amazingly well," Halbert said."We've found a significant decrease in predations by jays, the number of times eggs get broken," she said. The effects were monitored with camera traps and a second wave of mimic eggs.

Reducing predation on murrelet nests by 40 percent to 70 percent would stabilize the Santa Cruz Mountains murrelet population, according to the 2010 study published in the journal Biological Conservation. That 40 percent minimum would drop the extinction risk from about 96 percent to about 5 percent over 100 years, and result in stable population growth, reported lead study author Zach Peery of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In 2012, the smallest cutback in egg attacks by Steller's jays and other predators was 44 percent, and the biggest was as much as 80 percent in the two state parks, researchers reported. The project cost $80 per treated hectare (2.4 acres).

When the enemy is full, starve them

Here's why taste aversion works so well for Steller's jays. Their fiercely territorial social structure keeps out untrained birds. Long-lived, with excellent memories, the jays will recognize and avoid those rare blue-green eggs that made them retch. Nothing else in the forest looks like a murrelet egg. If taste-aversion training were to spread through the murrelet's range, it would not be the first time a bird would require human babysitters to survive — think of condors, who need devoted monitoring and care..

But Halbert said all the efforts to stop egg-stealing won't matter if the parks can't shrink the jay population by getting rid of their campground crumb food source. That's where the human psychology comes in. The parks hired an expert in public education and natural resources, Carolyn Ward, to help craft a message as finely tuned as any advertising company's.

"We're coming up with creative ways to change people's behavior," Halbert said.

Ward's research revealed most park visitors only read the first sentence on signs, so starting with the marbled murrelet's history was wasted effort. Now, with everything from stickers on the back of bathroom stalls to new signs at campsites, Redwood Parks visitors are warned to "Keep it crumb clean." This summer marks the new program's first big push, with campfire talks, tchotchkes for kids, brochures and YouTube videos that highlight the murrelet's plight.

At Big Basin Redwood State Park, Halbert has also installed animal-proof food lockers and trash cans. At Redwood National Park, the staff reconfigured the outdoor sinks so jays and squirrels can't steal leftovers from dishes.

While Redwood National Park is going “crumb clean,” the park will wait on the vomit eggs, Bensen said. "We're basically trying to prevent any food access to even the smallest crumb," he said. "With Steller's jays, just a couple Cheetos is enough. They'll keep coming and coming, and then eat the marbled murrelets. We want to cut that process off at the knees."

Future development

The "crumb clean" push comes as Big Basin gears up for a struggle over its first general plan, which will guide the park's future. The proposed plan, published in 2012, will expand areas of the park to new public use. But some groups, including the California Audubon Society and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, think the park should either close or restrict certain areas during murrelet breeding season, to help the endangered species recover.

A public hearing on the draft plan will be held today (May 17) in Santa Cruz, Calif., and a copy of the plan is available online.

"If people are looking for someone to blame for the problem the murrelet is having, I think everybody has some of that blame," Golightly said. "Cutting of the old-growth forests in the past is the primary thing that put us to this point, but presently, if you visit the parks and feed the animals, you're contributing, too. It is coming at the expense of the murrelet."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus