Facts About Chlorine

If you have ever taken a prescription medicine, driven a car or drunk tap water, you likely have been exposed to chlorine.

Chlorine, element No. 17 on the Periodic Table of Elements, has multiple applications. It is used to sterilize drinking water and to disinfect swimming pools, and it is used in the manufacturing of a number of commonly used products, such as paper, textiles, medicines, paints and plastic, particularly PVC, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry. Moreover, chlorine is used in the development and manufacturing of materials used in products that make vehicles lighter, from seat cushions and seat covers to tire cords and bumpers, according to the American Chemistry Council.

The element is also used in organic chemistry processes — for example, as an oxidizing agent and a substitution for hydrogen, according to the Los Alamos National Laboratory. An oxidizing agent has strong disinfecting and bleaching qualities. When used as a hydrogen substitute, chlorine can bring many desired properties in organic compounds, such as its disinfecting properties or its ability to form useful compounds and materials like PVC and synthetic rubber.

But chlorine also has a dark side: In its natural gas form, it is harmful to human health. Chlorine is a respiratory irritant, and inhaling it may cause pulmonary edema — an excessive buildup of fluid in the lungs that can lead to breathing difficulties. The gas can also cause eye and skin irritation, or even severe burns and ulcerations, according to the New York State Department of Health. Exposure to compressed liquid chlorine can result in frostbite of the skin and eyes, the agency reports.

Just the facts

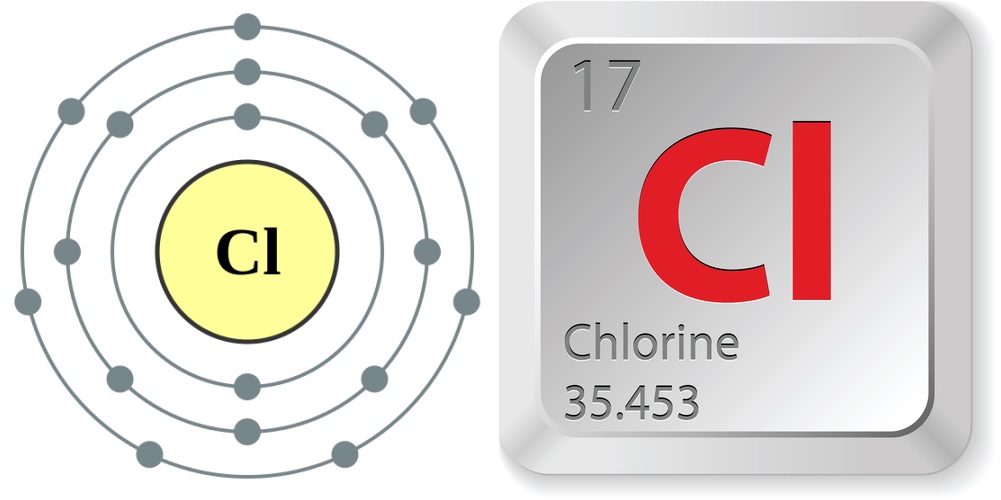

- Atomic number (number of protons in the nucleus): 17

- Atomic symbol (on the Periodic Table of Elements): Cl

- Atomic weight (average mass of the atom): 35.453

- Density: 3.214 grams per cubic centimeter

- Phase at room temperature: Gas

- Melting point: minus 150.7 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 101.5 degrees C)

- Boiling point: minus 29.27 F (minus 34.04 C)

- Number of isotopes (atoms of the same element with a different number of neutrons): 24. Number of stable isotopes: 2

- Most common isotopes: Chlorine-35 (76 percent natural abundance)

Greenish-yellow gas mistaken for oxygen

In 1774, Swedish pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele released a few drops of hydrochloric acid onto a piece of manganese dioxide in his lab, and a greenish-yellow gas was produced in a matter of seconds, according to the American Chemistry Council. However, chlorine was not recognized as an element until several decades later, by English chemist Sir Humphry Davy, and before that, people thought it was a compound of oxygen. Davy named it "khloros," from Greek word for greenish-yellow, and in 1810, he updated the name to "chloric gas," or "chlorine."

Chlorine belongs to the group of halogens — salt-forming elements — together with fluorine (F), bromine (Br), iodine (I) and astatine (At). They are all in the second column from the right on the periodic table in Group 17. Their electron configurations are similar, with seven electrons in their outer shell. They are highly reactive elements; when bonded with hydrogen, they produce acids. None are found in nature in their elemental form, according to Purdue University. They are typically found as salts in minerals.

In fact, probably the most known form of a chlorine compound is sodium chloride, otherwise known as table salt. Other compounds include potassium chloride, which is used to prevent or treat low potassium levels in the blood, and magnesium chloride, which is used to prevent or treat magnesium deficiency.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most chlorine is made via electrolysis of sodium chloride solutions — using an electric current to create a chemical reaction, according to the University of York. The process separates the elements.

Who knew?

- Due to its toxic properties, chlorine was used as a chemical weapon during World War I, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry.

- When isolated as a free element, chlorine takes the form of a greenish-yellow gas, which is 2.5 times heavier than air and smells like bleach.

- Chorine is the second-most-abundant halogen and the second-lightest halogen on Earth, after fluorine.

- Sodium chloride (salt) is the most common compound of chlorine and occurs in large quantities in the ocean.

- There may be some chlorine in the chicken you eat. Chicken carcasses that come from U.S. factory farms are often drenched in chlorine to get rid of fecal contamination.

- Chlorine destroys ozone, contributing to the process of ozone depletion. In fact, one chlorine atom can destroy as many as 100,000 ozone molecules before it is removed from the stratosphere, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

- Swimming pools rely on chlorine to help keep them clean. According to the American Chemistry Council, the water in most swimming pools should contain two to four parts per million of chlorine. And that strong chlorine that you may smell when swimming at the public pool may actually be an indicator that additional chlorine is needed to balance the chemicals in the water.

Research

Chlorine has caused quite a stir among researchers over the years because of certain harmful effects it may have on human health. Those effects, however, remain debatable.

Chlorine is one of the atoms in a toxin that some South American frogs have in their skin. It can paralyze or even kill large animals, according to the American Chemistry Council. Natives of the Colombian tropical rainforest used to rub the tips of their arrows on the skin of these "poison-dart frogs." John Daly, a scientist at the National Institutes of Health tried to isolate the compound, called epibatidine, but could not get enough of the substance (the frogs are endangered), and what he did synthesize had unwanted side effects. However, by rearranging the compound on the atomic level, chemists hope they can eventually find a version that is a potent pain reliever.

Previous research has linked drinking chlorinated water to an increased cancer risk. For example, in a study published in 1992 in the American Journal of Public Health, researchers found that people who drank chlorinated water had a 21 percent higher risk of getting bladder cancer, and a 38 percent higher risk of getting rectal cancer, than people who drank non-chlorinated water. And, in another study, published in 2010 in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, investigators found that people who swam in a chlorinated pool for 40 minutes had increased biomarkers (i.e., certain molecular indicators) related to cancer risk. However, a 2017 study published in the same journal found that while there is a higher bladder cancer risk when drinking chlorinated water, there was little to no evidence linking swimming in a chlorinated pool and bladder cancer risk in a study that looked at the number of hours in the swimming pool during summer and non-summer months and during different age ranges.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have not classified chlorine as a human carcinogen, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

So, is chlorine bad for your health? Not exactly, said Preston J. MacDougall, a professor of chemistry at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro.

"You don't want to use excessive amounts of chlorine, but we shouldn't fear chemical substances because we do not understand them," MacDougall told Live Science.

In fact, the lack of appropriate chlorination to kill harmful bacteria, such as E. coli, can have devastating consequences on human health and life, he added. For example, in May 2000, in Walkerton, Ontario, seven people died and more than 2,300 got sick after the town's water supply became infected with E. coli and other bacteria, according to the Water Quality and Health Council. If the required chlorine levels had been maintained, the disaster could have been prevented, even after the water was contaminated, according to a report published by the Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General.

Additionally, adding chlorine to water is one method that many are trying to make clean water easily accessible in developing countries. A study published in 2017 states that 3.4 million people die each year from water contaminated with harmful bacteria, such as E. coli, and that up to 4.4 billion people do not have a reliable source of clean drinking water. Chlorinating the water supply in addition to bringing water closer to the communities is one important step in bringing clean water closer to those who need it.

In addition, there is some promising research-related news about chlorine. MacDougall pointed to a recent study on chlorine atoms found in a novel class of antibiotic compounds that have been discovered in tiny marine organisms in North Atlantic waters near Norway. Those chlorine atoms are essential to the antibiotic activity of the compounds, which can be effective against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterium that causes hard-to-treat infections in people and is resistant to commonly used antibiotics, he said.

"The drug discovery community is very excited about these naturally occurring compounds because they are effective against MRSA," said MacDougall, who was not involved in the research, published in April 2014 in the journal Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

Additional reporting by Rachel Ross, Live Science contributor.

Additional resources

- To see how reactive chlorine is when it interacts with other compounds, check out this fun video made by Periodic Videos.

- Learn about the numerous surprising applications of chlorine on this website called Elements of Surprise that is dedicated to this versatile element.

- If you want to learn more about how exposure to chlorine may affect your health, check out the chlorine FAQ section on the CDC website.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus