Scientists spot water molecules flipping before they split, and it could help them produce cheaper hydrogen fuel

Splitting water molecules takes more energy than calculations suggest, and is a key roadblock to cheap hydrogen fuel production. Now, scientists have discovered why.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For the first time, scientists have observed water molecules splitting in real time to form hydrogen and oxygen.

And right before they split, the molecules did something completely unexpected: They flipped 180 degrees.

This micro acrobatic stunt takes energy, which offers a crucial explanation for why splitting water takes more energy than theoretical calculations suggested.

The researchers say that studying this further could offer key insights into making the process of splitting water molecules more efficient — opening a pathway to cheaper clean hydrogen fuel and breathable oxygen for future Mars missions. They published their findings March 5 in the journal Science Advances.

Making hydrogen fuel

Hydrogen has a number of key properties that make it an enticing source of green energy. The energy-rich fuel is capable of powering trucks and even cargo ships, and it is the only alternative to fossil fuels in industries such as steel and fertilizer manufacturing. When it's burned, the fuel releases water instead of carbon dioxide.

Yet the steep energy requirements for hydrogen production severely limit the scale at which the fuel is produced. According to the International Energy Authority, 322 million tonnes (354 million tons) of hydrogen fuel needs to be produced each year to meet global energy needs. But in 2023, only 97 million tonnes (107 million tons) was manufactured at a monetary cost 1.5 to six times greater than fossil fuel production — and the vast majority of it was made using fossil fuels too.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

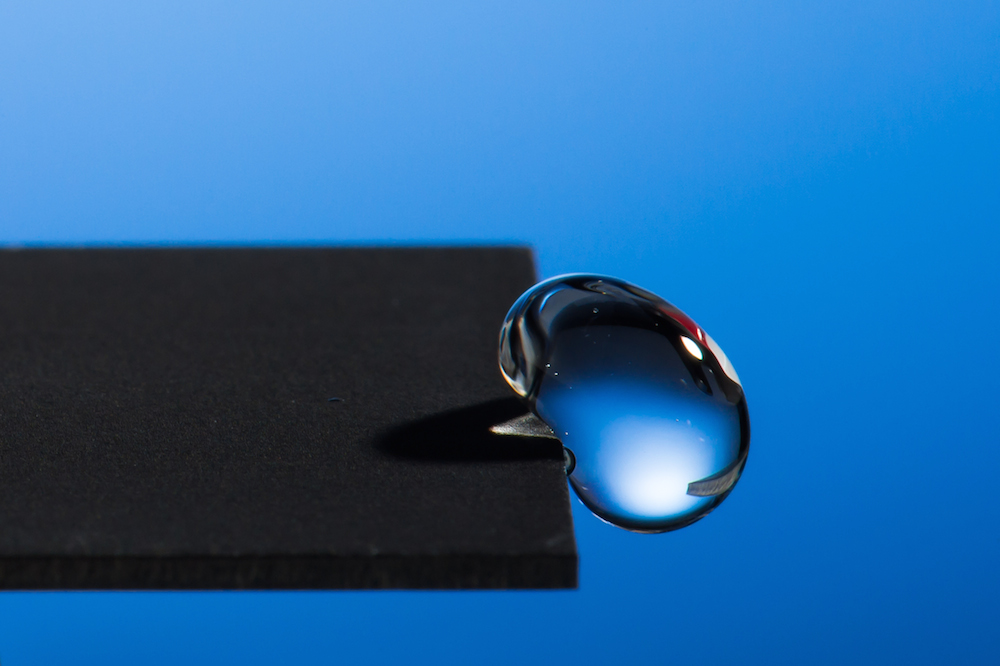

Hydrogen fuel is made by adding water to an electrode and then splitting the water with an applied voltage into hydrogen and oxygen.

This process is most efficient when the chemical element iridium is used as a catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction that cleaves oxygen from water molecules. But iridium only arrives on our planet from meteorite impacts, making it costly and scarce.

But even when using iridium, the process is less efficient than scientists believe it should be.

"It ends up taking more energy than theoretically calculated. If you do the math, it should require 1.23 volts. But, in reality, it requires more like 1.5 or 1.6 volts," study lead author Franz Geiger, a professor of chemistry at Northwestern University, said in a statement. "Providing that extra voltage costs money, and that's why water splitting hasn't been implemented at a large scale."

To better understand the energy requirements of this process and why it's less efficient than theory suggests, the researchers placed water on an electrode inside a container and measured the molecules' positions using the amplitude and phase of laser light shone onto them.

When the scientists applied a voltage across the electrode, they observed that the molecules rapidly flipped and rotated so that their two hydrogen atoms touching the electrode faced up and the oxygen atom faced down.

"Electrodes are negatively charged, so the water molecule wants to put its positively charged hydrogen atoms toward the electrode's surface," Geiger said. "In that position, electron transfer from water's oxygen atom to the electrode's active site is blocked. When the electric field becomes strong enough, it causes the molecules to flip, so the oxygen atoms point toward the electrode's surface. Then, the hydrogen atoms are out of the way, and the electrons can move from water's oxygen to the electrode."

By measuring the number of molecules that rotated and the energy required for them to do so, the researchers found that this flipping was likely a necessary and unavoidable part of the splitting process. What's more, the researchers discovered that higher pH levels made this process more efficient.

Further studying this process could help scientists to design more efficient catalysts to use in the process, and to better understand the chemical processes involved, the researchers said, while also offering fresh insights into how water behaves.

"Our work underscores how little we know about water at interfaces," Geiger said. "Water is tricky, and our new technology could help us understand it a bit better."

"By designing new catalysts that make water flipping easier, we could make water splitting more practical and cost-effective," he added.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus