Why You Are Paying for Everyone's Flood Insurance

Andy Stevenson, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) Finance Advisor and Dan Lashof, Director of NRDC's Climate and Clean Air Program contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

There are many, many compelling and urgent reasons to take decisive action to combat climate change. Here's one that's measurable by dollars added to our budget deficit. Actually by tens of billions of dollars.

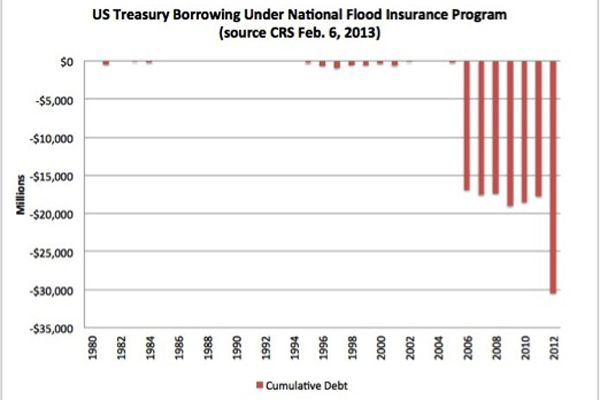

The soaring cost of private flood insurance is pricing so many coastal homeowners out of the market that the rest of the American taxpayers are having to bail them out – to the tune of $30 billion under the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

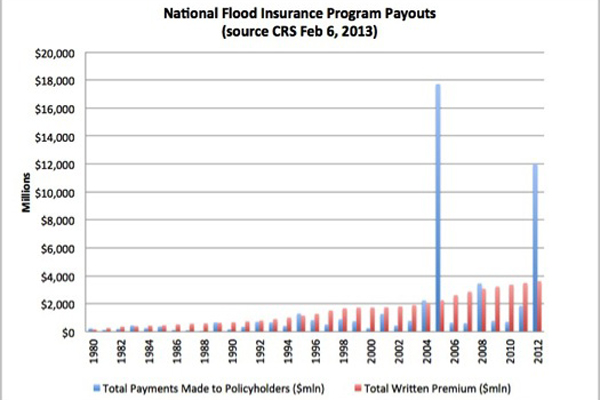

With over $139 billion in storm, wildfire, drought, tornado and flood damages taking nearly 1 percent of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) in 2012, the insurance industry is referring to last year as the second costliest year on record for U.S. climate-related disasters. And while insurers do include $12 billion worth of flood-related damages in their estimates, they aren't the ones getting stuck with most of the bill. It's us, the taxpayer.

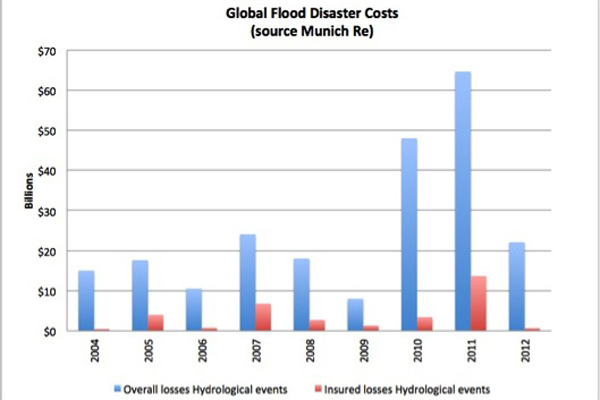

On a global basis, the insurance company Munich Re estimates that flooding represented 16 percent of total climate-related damages over the past decade, or $25 billion, on average, per year. Over that same period, insurers paid out on $3.75 billion per year, on average, or less than 15 percent of total flood-related costs. That percentage seems to be fairly representative as the total losses from floods along the Mississippi in 2011 were estimated at $4.6 billion with only $500 million (11 percent) covered by private insurers.

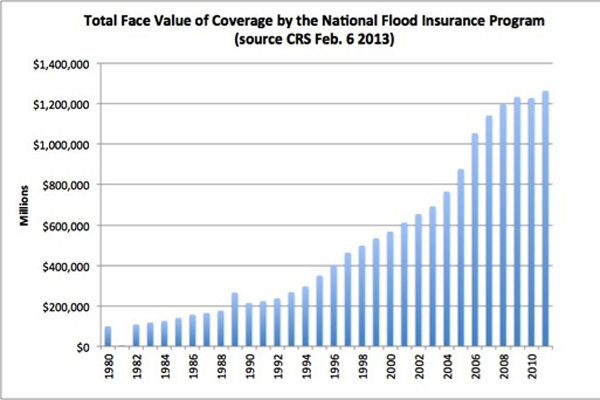

So if insurers are only paying 10-15 percent of the bill, who actually does pay the cost of flood-related damage? The not-so-surprising answer is you and me, largely through the National Flood Insurance Program, which has nearly $1.3 trillion in policies outstanding. This program includes several state programs, such as the one for Florida (which has over 2 million policy holders and a face value of $475 billion) that had to be created as the rising cost of flooding was not being covered by private insurers.

This massive federal program has nearly doubled in size over the past decade as private insurers have continued to shy away from making bets against Mother Nature when it comes to floods. And while the federal government has picked up the slack in terms of coverage, it has had a tough time balancing the premiums that are paid in with the heavy losses it has sustained from recent climate related events.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In fact, following an estimated $12 billion in payout to 140,000 policy holders from Superstorm Sandy, the program is over $30 billion in debt and has Congress scratching its head about what to do about it since the private insurers have made it very clear this is not a business that they wish to be in. NFIP is insolvent because premiums don't reflect actual risks; and it's hard to make a case that climate-change-charged storms are not a big part of the reason why. [Jersey Shore: Before and After Hurricane Sandy]

In sum, the U.S. taxpayer is currently down $30 billion trying to provide insurance for coastal landowners that no longer have access to affordable private flood insurance. And that figure does not include the costs weathered by the state-based programs that have been set up due to a lack of private alternatives available to their residents. Taken together, these programs constitute a climate disruption tax that the U.S. consumer is being forced to pay to cover risks that the insurance industry, the true score-keepers on climate, won't touch.

As the costs of climate change continue to mount, it is becoming increasingly obvious that we can't afford not to act to rein in the carbon pollution that is supercharging storms and floods. Fortunately President Obama has a big opportunity to reduce emissions from power plants, America's biggest carbon polluters. Under a plan NRDC put forward in December, we could cut these emissions by 26 percent by 2020 and 34 percent by 2025 compared to 2005 levels. The plan provides great flexibility to states and utilities, and offers benefits to every American.

Its benefits—worth between $25 and $60 billion in 2020 — far outweigh the plan's costs — about $4 billion. Implementing it will save tens of thousands of lives through reductions in air pollution. And it will drive investments in energy efficiency and clean energy that will create thousands of new jobs across the nation. Now that's an insurance premium worth paying.

Editor’s Note: Andy Stevenson and Dan Lashof blog on NRDC's Switchboard.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.