Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Winter snowstorms, like the Nor'easter that just slammed New England, transform gray days into winter wonderlands.

So while you're stuck inside, or within snowshoe-walking distance, here are six fun facts about snow, from the idea that no two snowflakes are alike to the bizarre megadunes that blanket Antarctica.

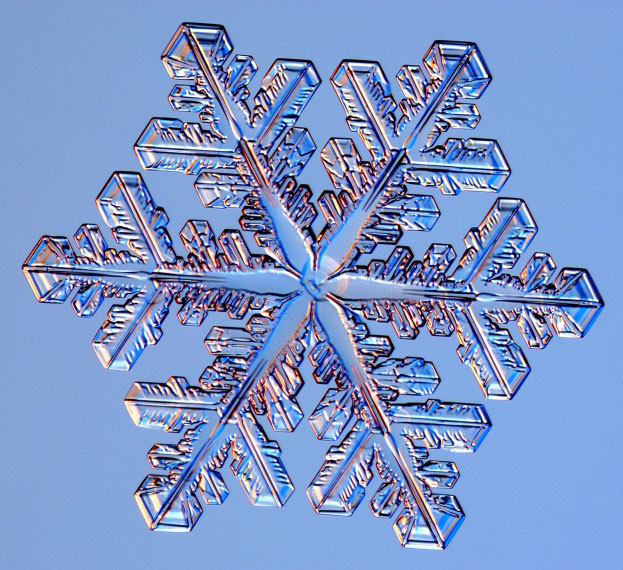

Unique beauty

According to physicists, it's actually true that no two snowflakes are alike — well, at least when it comes to complex snowflakes.

Snowflakes form when water droplets in the clouds freeze to form a six-sided crystal structure. As the temperature cools, more water vapor freezes and grows in branches from the six sides of the seed crystal. As the crystals form, they are randomly tossed about inside the clouds, which vary in temperature.

The temperature greatly affects how the snowflake forms, so while the simplest hexagonal crystals may look alike, more complicated beauties each have their own unique shapes. [See Stunning Photos of Snowflakes]

White triangles

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most snowflakes form dazzling crystal patterns with six sides. But occasionally, a triangular crystal forms, something that has puzzled physicists for years. A 2009 study in the open-access, pre-publish journal arXiv.org revealed that triangular snowflakes form when the six sides of the seed crystals are slightly asymmetric. This makes them wobble randomly as a snowflake falls, allowing the bigger sides to hit the fast-flowing air inside the cloud, and grow at the expense of the smaller sides.

Other snowflakes have even stranger shapes: Some look like hourglasses, others like spools of thread and still others like needles. And while the quintessential snowflake is the six-armed, symmetrical beauty, most versions are hardly so picturesque. In fact, since the arms of a snowflake all grow randomly, asymmetrical snowflakes are more common.

Snowy shapes

The types of snowflakes that form depend a lot on the temperature and moisture in the clouds, according to a 2005 review in the journal Reports on Progress in Physics. Right around freezing temperatures, hexagonal plates (the cross-section is a two-dimensional hexagon) and the iconic, six-sided snowflake (known as a dendrite) form.

As the temperature cools, snowflakes develop into needles, then hexagonal prisms and even hollow columns. Go colder still, and dendrites form at much larger sizes. And at truly frigid temperatures, the frigid air forms prisms and flat plates.

Piles and piles

Because snow is so fluffy (meaning it's chock full of air), a relatively small amount of water can translate into a huge pile of snow. An inch of rain on average makes about 10 inches of snow. The biggest snowfalls on record are hard to compare, but the Great Snow of 1717 dropped about 3 to 4 feet (0.9 to 1.2 meters) on Boston inhabitants, with some drifts reaching 25 feet (7.6-m), according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

In 1959, a snowstorm in Mt. Shasta dropped as much as 15.75 feet (4.8 meters) on inhabitants of the California region, according to the College of the Siskiyous. In the 1998 to 1999 snow season, about 95 feet (28.9 m) of snow fell on Mt. Baker, Wash.

Graupel and Hoar Frost?

An old saying claims the Eskimos have dozens of different words for describing snow. While that turned out to be a myth, there are many types of snow crystals and even more snow formations. Aside from the snowflake, there's also hoar frost and graupel, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Hoar frost forms on surfaces that are colder than the frost point in the air around them, so water goes straight from vapor to solid. This spiky, fluffy snow tends to form on tree branches, telephone wires and other skinny items exposed to the chilly air. Graupel, which consists of hard ice pellets, forms when snowflakes fall through a cloud that contains supercooled water droplets. The droplets freeze onto the snowflakes and form misshapen, lumpy balls.

Snow landscape

While the snow on the driveway may just be a pile, the fluffy white stuff creates beautiful formations in nature. Lovers of winter sports know to be wary of cornices, overhanging snow that juts from the edge of a cliff.

And in Antarctica, giant snow formations known as megadunes form from monstrous snow crystals that are up to 0.75 inches (2 cm) across, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center. (There can be several snow crystals in a single snowflake.) In arid locales like Death Valley, Calif., piles of snow can be transformed into penitents: bizarre, spiky formations that look like the stalagmites that form in caves.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus