Women Out-Earn Men Online: Gaming Study

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

On the Internet, no one has to know if you're a man or a woman — theoretically. But new research finds that men and women arrange their online social lives differently, with men taking more risks and cultivating less-stable social networks than their female counterparts.

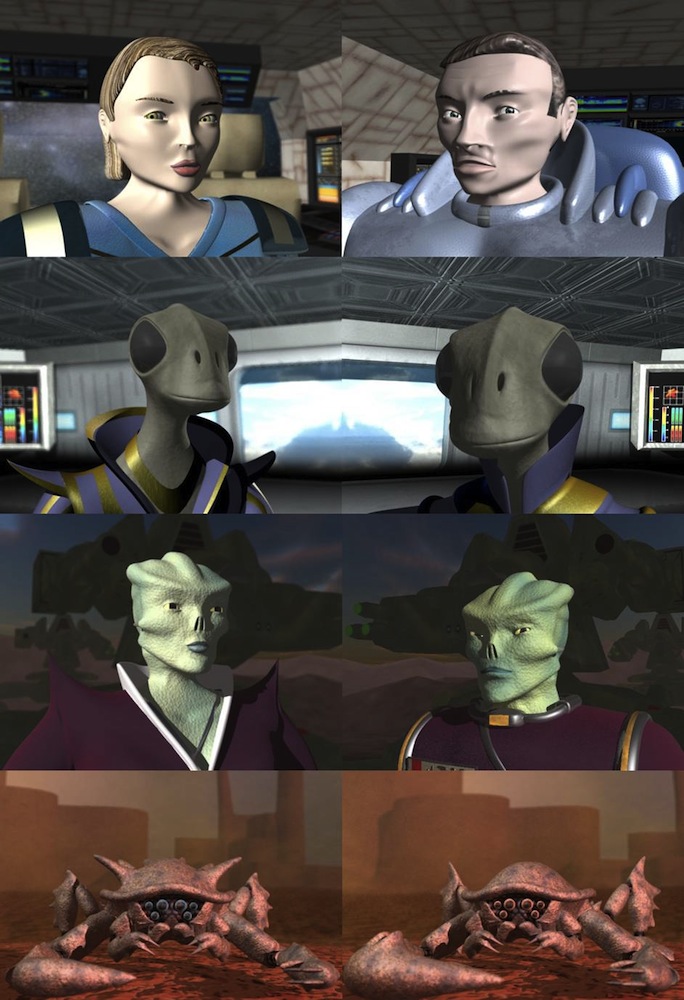

The study used a Massive Multiplayer Online Game (MMOG) called Pardus to track the behaviors of about 300,000 players. Though the game is set in a fantasy world in space, these MMOGs have previously been shown to match real-life behavior with surprising accuracy, said study researcher Stefan Thurner of the Medical University of Vienna.

"What I find fascinating is that by using a 21st century MMOG game, we can learn something about biological facts of our species," Thurner told LiveScience.

Playing at society

Pardus allows users to choose a character, the gender of which cannot be changed later, and to interact with other characters in a complex world of war, trade, friendship and enmity. Thurner and his colleagues had already delved into the world of online gaming to find that everything from virtual commodity pricing to friendship networks follows similar patterns to those seen in the real world. Intriguingly, they found, female characters in the game took fewer risks than male characters, but were still more economically successful.

The researchers decided to find out why, a process that led them to look at how social networks in the game form. Though they had no information on player's actual gender, the researchers assumed that most people choose characters that match their real-world gender, because studies of other MMOGs suggest that only about 15 percent of people gender-swap online.

The results revealed that in the online world, women are the money-makers. The ladies of Pardus earned more virtual moolah than guys. They also participated in less aggression, dying less often as a result.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Women's economic savvy also revealed itself in their trade networks, which were tighter-knit than those developed by men. Women chose to stick together, trading more often with other women than with men. Women communicated with about 15 percent more other players than men did, on average, and clustered their communications about 25 percent more, meaning that they traded with people who tended to keep their trade among themselves. They also reciprocated friendships 20 percent more often than men did. [10 Ways to Keep Your Mind Sharp]

Men, on the other hand, preferred to connect with other players who themselves connected with a lot of people. Men also perked up when the chance to interact with a woman came along. A woman making a friendship overture in the game to a man could expect a positive response almost immediately, Thurner said. In contrast, a man seeking to befriend a woman could expect to have to wait while she weighed his offer. (Women are relatively scarce in the world of online gaming. In Pardus, the researchers report, 8 to 9 times more men than women play.)

"Maybe what we see is something very old in an evolutionary sense, where females build tight and compact social networks, whereas men are communicating in a way that gives them as much of an overview of a situation in a most efficient way," Thurner said.

Online and offline

Thurner warned that the link between evolution and online role-playing isn't yet proven; other factors such as culture or socialization could explain the gender differences as well. Gender-swapping might also affect the results, Thurner said, though the impact is likely "marginal."

The researchers next plan to study how conflicts form in social networks, given that Pardus is a world full of fighting, from two-person feuds to wars between thousands. More work will be needed to link all of this online activity to the real world, Thurner said, but watching people interact online is a rich source of information on how people network.

"The problem is that such data is still very hard to obtain in real-world situations. In this respect, the environment of computer games is certainly almost ideal — with the problem that it is a bit of an 'artificial' society,'" he said. "But on the other hand, what is a 'real' and non-artificial society?"

The researchers report their findings online Feb. 7 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus