Climate Change to Claim San Francisco Marshes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

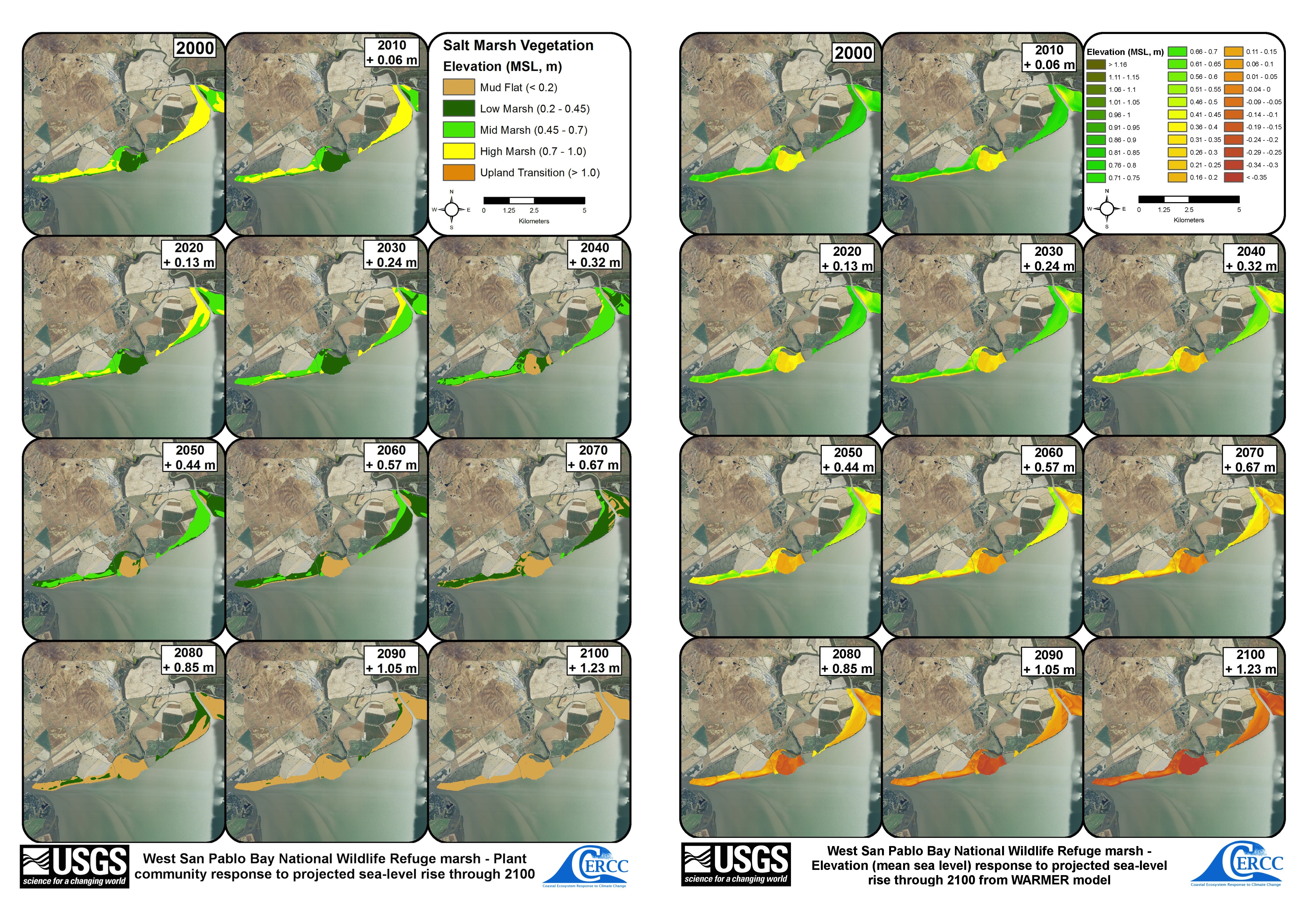

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — More than 80 percent of critical salt marsh habitat around San Francisco Bay will disappear in 100 years due to rising sea levels, according to a detailed, decade-long survey of the area by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

The marshes are the bay's natural buffer against rising seas. Many of the Bay Area's cities and important services, including highways, airports and power lines, lie only a few inches to a few feet above sea level. As long as a marsh accumulates enough sediment to keep pace with encroaching sea levels, it can maintain its elevation, protecting nearby homes and infrastructure.

Marshes can also retreat, but in the central and South Bay, development surrounds all existing marshes, leaving them nowhere to go.

For its report, the USGS surveyed roughly 8 square miles (20 square kilometers) of the remaining tidal marshes in San Francisco Bay, an estuary that contains about 80 percent of California's wetlands.

If current trends continue, only 12 percent of this region will survive as marsh until 2100, the USGS found. The rest will turn into mudflats, or drown.

The sole marsh expected to survive is in the South Bay, where sediment pours in from the Sierra Nevada Mountains. But it will be "low" habitat, dominated by cordgrass, not the mid-to-higher-elevation plants like pickleweed favored by local wildlife, such as the federally endangered salt marsh harvest mouse and the California clapper rail, a type of bird.

High-marsh species, as result, face the most risk from rising seas, said Karen Thorne, a research ecologist at the USGS Western Ecological Research Center in Sacramento who helped author the report. Living at higher elevations, their habitat will disappear altogether by 2100, Thorne said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I feel like these are really important results, and I hope people will take this information and do something with it," she said. "These are the results if we do nothing.

"I'll be the first to acknowledge that [the high marsh] won't be there in 2100, but there is temporary value in restoration," Thorne told OurAmazingPlanet. "The 'how' part, that's the big question."

Marsh restoration effects

The projections heighten the urgency of completing restoration projects at marshes within the San Francisco Bay's national wildlife refuges, said Eric Mruz, manager of the Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge.

"We have to start restoring these now, or else it's going to be too late," Mruz told OurAmazingPlanet. "You're going to have just sea walls and open water. We've already lost 85 percent of the tidal marshes in our open areas, so if we don't restore some of these areas now, we're never going to get [them] back."

Billions of dollars have been invested in marsh restoration projects throughout the bay, from the South Bay Restoration Project in Mruz's home turf to projects that just broke ground. One recently begun project is the Cullinan Ranch Project in the North Bay, near the Napa River estuary and Highway 37, part of a grand plan to convert agricultural land in that area back to marsh.

Don Brubaker, who oversees the Cullinan Ranch restoration for the San Pablo National Wildlife Refuge, said the planning accounted for sea level rise. Building marsh habitat now will help threatened and endangered species weather coming changes in the bay, he said. [Gallery: Species on Endangered 'Red List']

"If we can get some of these restorations up and running, we'll have that much more time to farm these types of species that need this type of habitat," Brubaker told OurAmazingPlanet. The Napa River estuary also has room to move back with rising sea level, he noted. "We do have that ability to creep," Brubaker added. "Getting the marsh established now allows it to keep pace better with sea level rise."

Projections and modeling

The USGS projections are based on the WARMER model (published in 2008 in the journal Climate Change), which predicts 4 feet (1.24 meters) of sea-level rise in the bay by 2100. USGS researchers with the Western Ecological Research Center in Sacramento surveyed the marshes on foot and by air for 10 years, collecting records of plant and wildlife, soil, tides, water depth and ground elevation.

Because the amount of predicted sea-level rise may change in the future, the projections for each marsh can be changed as new models for the Bay Area are published, Thorne said. The reports and data are also freely available online.

The 12 marshes included in the report are in the following areas:

- San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge

- China Camp State Park

- Corte Madera Ecological Reserve

- Fagan Ecological Reserve

- Cogswell Marsh, Arrowhead Marsh

- Colma Creek Marsh

- Laumeister Marsh

- Coon Island Marsh

- Black John Marsh

- Petaluma Marsh

- Gambinini Marsh

- Arrowhead Marsh

The next step is expanding the study to estimate the effects of sea level rise on marsh habitat along the entire West Coast, much as the USGS predicts hurricane damage for the East Coast.

Pilot studies are underway in San Diego, the Corte Madera Marsh in Marin County and Humboldt Bay in Northern California, Thorne said. She hopes to expand to Seal Beach in Orange County, then Oregon and Washington.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus