Weird Underwater Volcano Discovered Near Baja

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

SAN FRANCISCO — Scientists have discovered one of the world's weirdest volcanoes on the seafloor near the tip of Baja, Mexico.

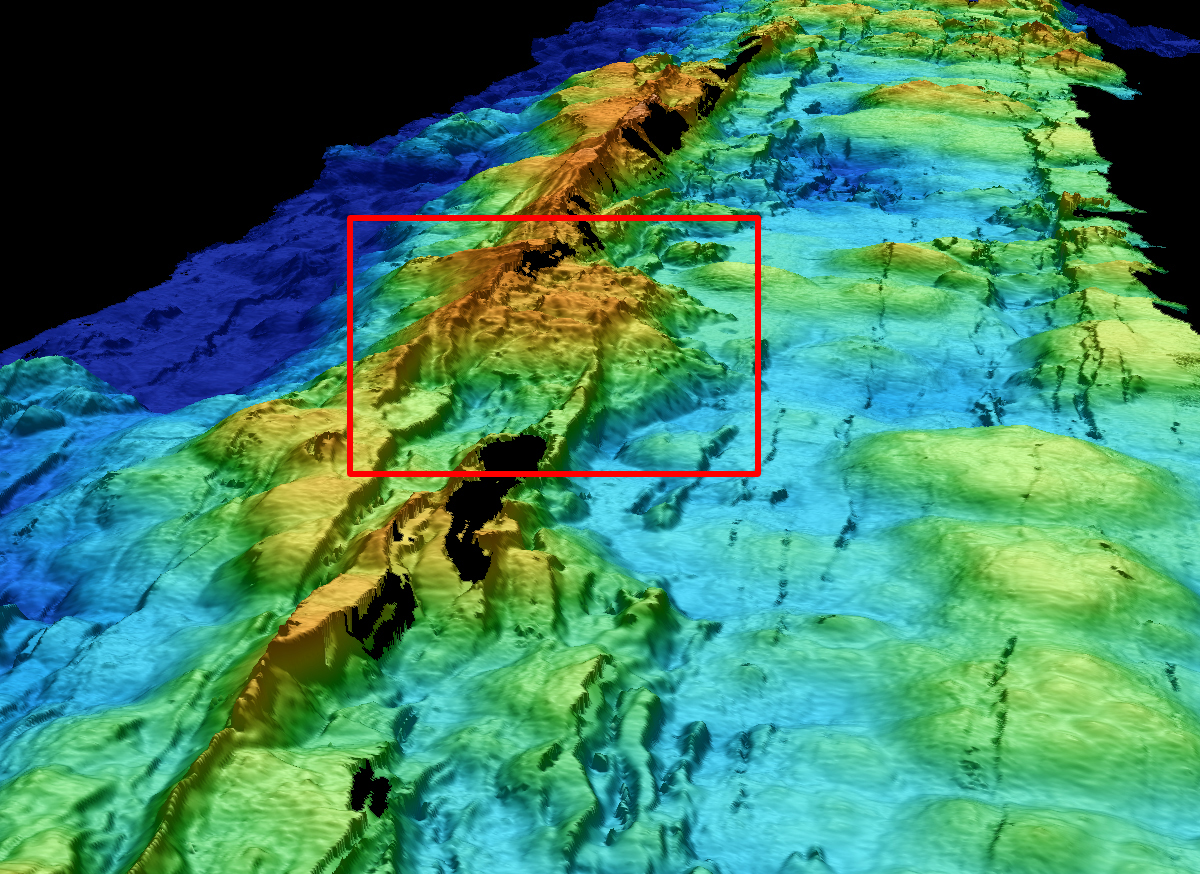

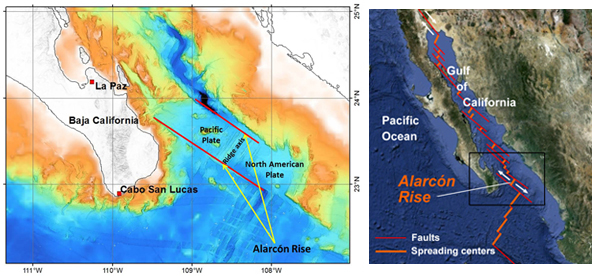

The petite dome — about 165 feet tall (50 meters) and 4,000 feet long by 1,640 feet wide (1,200 m by 500 m) — lies along the Alarcón Rise, a seafloor-spreading center. Tectonic forces are tearing the Earth's crust apart at the spreading center, creating a long rift where magma oozes toward the surface, cools and forms new ocean crust.

Circling the planet like baseball seams, seafloor-spreading centers (also called midocean ridges) produce copious amounts of basalt, a low-silica content lava rock that makes up the ocean crust. (Silica, or silicon dioxide, is the main component of quartz, one of the most common minerals on Earth.)

But samples from the newly discovered volcano are strangely rhyolite lava, and have the highest silica content (up to 77 percent) of any rocks collected from a midocean ridge, said Brian Dreyer, a geochemist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. The results were presented last week at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union. [50 Amazing Volcano Facts]

'A total surprise'

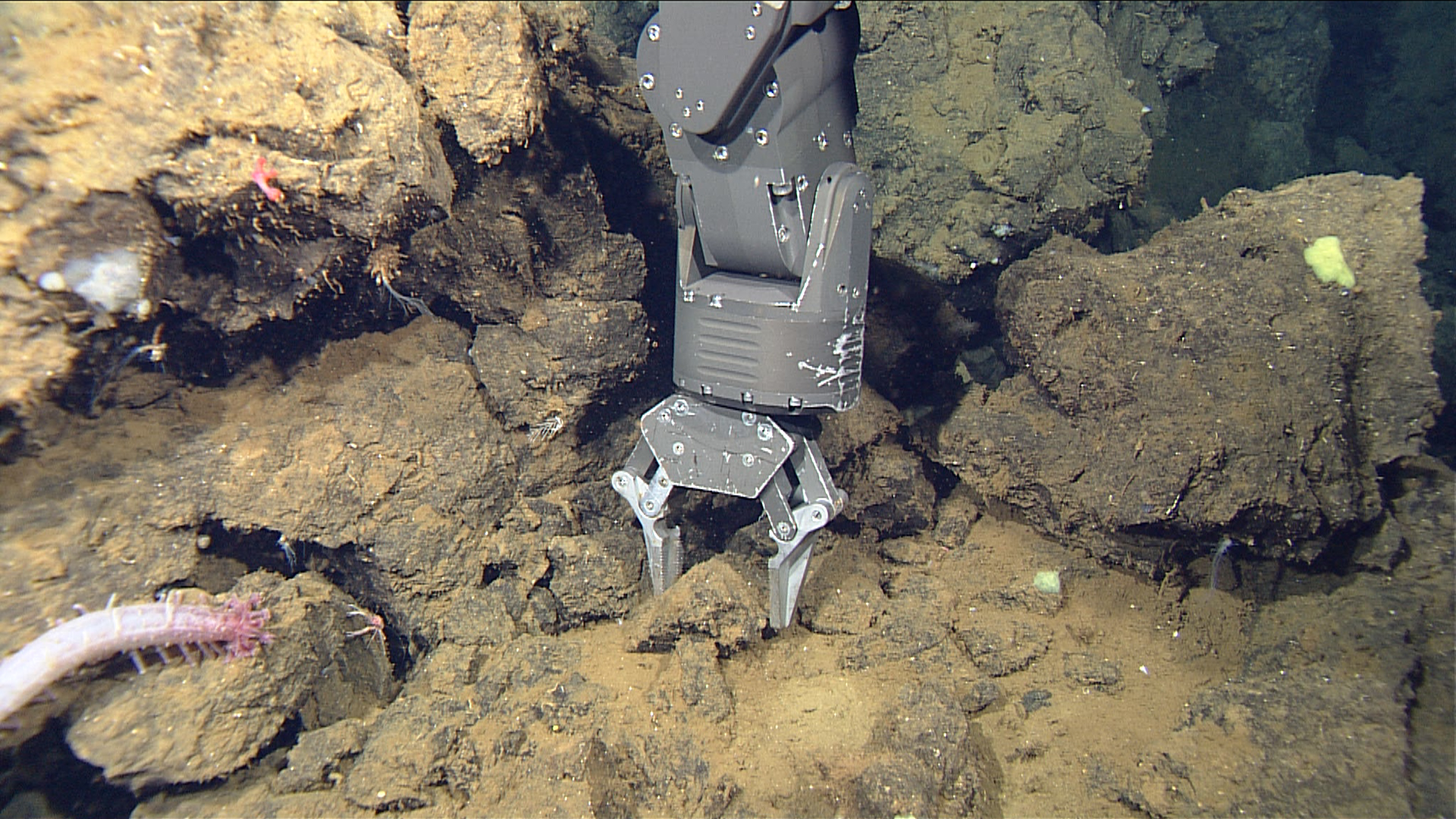

Researchers with the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) discovered the volcano this spring, during a three-month expedition to the Gulf of California, the warm stretch of water that separates Baja from mainland Mexico. A remote-control vehicle explored the volcano, which is 7,800 feet (2,375 m) below the surface, and brought samples back to the ship.

"When we picked up the rocks and got them back on the ship, we immediately noticed that they were very low density, and they were very light, glassy and gray. They were not the usual dark, black, shiny basalts," Dreyer told OurAmazingPlanet. "So we immediately knew that something was unusual."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The volcano is primarily rhyolite and a silicic lava called dacite, said MBARI geologist Jennifer Paduan. "To find this along a midocean ridge is a total surprise," she told OurAmazingPlanet.

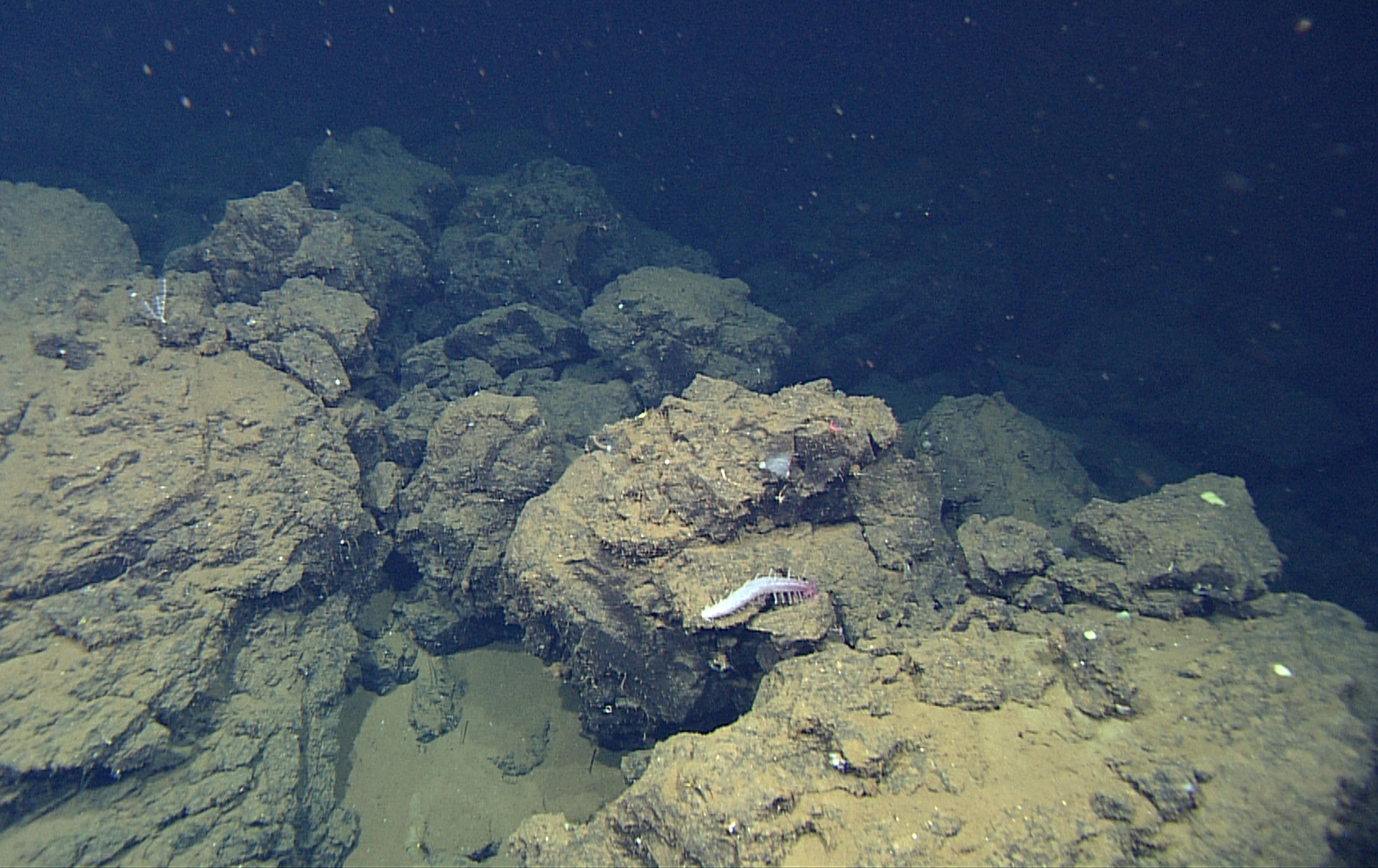

Boulders and blocks the size of cars and small houses littered the steep slopes of the dome, the robot's video camera showed. The gravelly debris is made of lava that resembles the ragged surface of a'a (rough, rubbly or blocky lava). The flows would have been deposited via large, avalanchelike deposits, Paduan wrote on the expedition's blog. A few ridges were composed of very strange, steeply dipping, lineated flows very different from the pillow-style appearance of deep-sea basalt, she wrote.

The researchers don't yet know how the age of the volcano because their samples haven't finished undergoing the necessary tests. The dome is probably several thousand years old, MBARI geologist David Clague said in an email interview.

Could it go boom?

Of more concern is the evidence for explosive volcanism, which is typical of rhyolite volcanoes, Paduan said.

"It's only 100 kilometers [60 miles] from land. When the sun is setting, you can see Cabo," she said. Both the Baja Peninsula and mainland Mexico near Alarcón Rise have cities and luxury resorts. The Gulf of California is also home to endangered sea life.

Rhyolite lava carries more gas and volatiles (things that are likely to cause explosions) than basalt, and when magma meets water, it vaporizes instantly, driving an even more explosive eruption.

"There's definitely explosive deposits there, and that is of extreme concern, given that the ridge is so close to land and the tsunami potential of a big explosion there," Paduan said. "We don't know how explosive, and that is something we are definitely trying to figure out."

The researchers also found Pele's seaweed, or limu o pele, at another location on the 30-mile-long (50 km) ridge. These are little fragments of lava formed from explosive magmatic gas bubbles that implode when they hit cold seawater. "We did find evidence of mildly explosive eruptions on the ridge," Paduan said.

Why is it there?

Rhyolites have been found on spreading centers, but only above hot spots, such as in Iceland and the Galapagos Islands, Dreyer said. Hot spots are plumes that bring magma to the surface from deep within Earth's mantle. There is no hot spot under the Alarcón Rise, he said.

Rhyolite lava typically occurs only on continents, such as in Mount St. Helen's growing dome in Washington. One possible explanation for the bizarre composition of the Alarcón volcano is that continental crust snuck into the molten rock below — the spreading center is young, and continental crust lies close by. But tests of different isotopes (versions of elements with differing numbers of neutrons in the cores) in the lava samples revealed no evidence of contamination by continental crust, Dreyer said.

Another discarded idea was that a cold spot underlying the ridge cooled and crystallized the magma chamber that fed the volcano, leaving only a high-silica melt behind. The team's current hypothesis is that the magma source had a high concentration of volatiles like water, sulfur and chlorine, maybe from an influx of seawater.

"It's a work in progress, but we have found some of the glassy volcanic debris surrounding this feature has water concentrations of up to eight percent, which is pretty unusual for a spreading center," Dreyer said.

The Alarcón Rise drifts apart at a relatively slow 2 inches (5 centimeters) a year. The segment is bounded by the Pescadero transform fault to the north and the Tamayo transform fault to the south, and is the northern extension of the East Pacific Rise. The vast majority of lava flows along the ridge are basalt. The rhyolite dome is about 5.5 miles (9 km) south of the Pescadero transform fault.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus