Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Does Mr. Whiskers really love you or is he just angling for treats?

Until recently, scientists would have said your cat was snuggling up to you only as a means to get tasty treats. But many animals have a moral compass, and feel emotions such as love, grief, outrage and empathy, a new book argues.

The book, "Can Animals Be Moral?" (Oxford University Press, October 2012), suggests social mammals such as rats, dogs and chimpanzees can choose to be good or bad. And because they have morality, we have moral obligations to them, said author Mark Rowlands, a University of Miami philosopher.

"Animals are owed a certain kind of respect that they wouldn't be owed if they couldn't act morally," Rowlands told LiveScience.

But while some animals have complex emotions, they don't necessarily have true morality, other researchers argue. [5 Animals With a Moral Compass]

Moral behavior?

Some research suggests animals have a sense of outrage when social codes are violated. Chimpanzees may punish other chimps for violating certain rules of the social order, said Marc Bekoff, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and co-author of "Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals" (University Of Chicago Press, 2012).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Male bluebirds that catch their female partners stepping out may beat the female, said Hal Herzog, a psychologist at Western Carolina University who studies how humans think about animals.

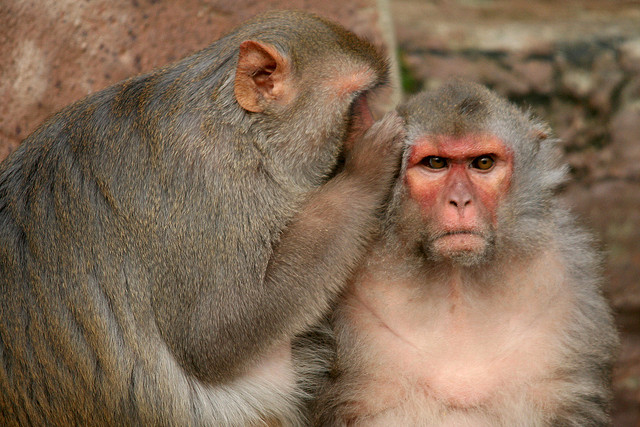

And there are many examples of animals demonstrating ostensibly compassionate or empathetic behaviors toward other animals, including humans. In one experiment, hungry rhesus monkeys refused to electrically shock their fellow monkeys, even when it meant getting food for themselves. In another study, a female gorilla named Binti Jua rescued an unconscious 3-year-old (human) boy who had fallen into her enclosure at the Brookline Zoo in Illinois, protecting the child from other gorillas and even calling for human help. And when a car hit and injured a dog on a busy Chilean freeway several years ago, its canine compatriot dodged traffic, risking its life to drag the unconscious dog to safety.

All those examples suggest that animals have some sense of right and wrong, Rowlands said.

"I think what's at the heart of following morality is the emotions," Rowlands said. "Evidence suggests that animals can act on those sorts of emotions."

Instinct, not morals?

Not everyone agrees these behaviors equal morality, however.

One of the most obvious examples — the guilty look of a dog that has just eaten a forbidden food — may not be true remorse, but simply the dog responding appropriately to its owner's disappointment, according to a study published in the journal Behavioural Processes in 2009.

And animals don't seem to develop or follow rules that serve no purpose for them or their species, suggesting they don't reason about morality.

Humans, in contrast, have a grab bag of moral taboos, such as prohibitions on eating certain foods, committing blasphemy, or marrying distant cousins.

"What I think is interesting about human morality is that often times there's this wacky, arbitrary feature of it," Herzog said.

Instead, animal emotions may be rooted in instinct and hard-wiring, rather than conscious choice, Herzog said.

"They look to us like moral behaviors, but they're not rooted in the same mire of intellect and culture and language that human morality is," he said.

Hard-wired morality

But Rowlands argues that such hair-splitting is overthinking things.

In the case of the child-rescuing gorilla Binti Jua, for instance, "what sort of instinct is involved there? Do gorillas have an instinct to help unconscious boys in enclosures?" he said.

And even if instinct is involved, human parents have an instinctive desire to help their children, but that makes the desire no less moral, he said.

Being able to reason about morality isn't required to have a moral compass, he added. A 3-year-old child, for instance, may not consciously articulate a system of right and wrong, but will (hopefully) still feel guilty for stealing his playmate's toy. (Scientists continue to debate whether or not babies have moral compasses.)

If one accepts that animals have moral compasses, Rowlands argues, we have the responsibility to treat them with respect, Rowlands said.

"If the animal is capable of acting morally, I don't think it's problematic to be friends with your pets," he said. "If you have a cat or a dog and you make it do tricks, I am not sure that's respect. If you insist on dressing them up, I'm not sure I'm onboard with that either."

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus