Discovery: Ancient Fort Aided Julius Caesar's Conquest of Gaul

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Updated Sept. 18 at 11:20 a.m. ET

Archaeologists say they've identified the oldest known Roman military fortress in Germany, likely built to house thousands of troops during Julius Caesar's conquest of Gaul in the late 50s B.C. Broken bits of Roman soldiers' sandals helped lead to the discovery.

"From an archaeological point of view our findings are of particular interest because there are only few sites known that document Caesar's campaign in Gaul," researcher Sabine Hornung, of Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz (JGU), told LiveScience in an email.

Researchers knew about the large site — close to the German town of Hermeskeil, near the French border — since the 19th century but lacked solid evidence about what it was. Parts of the fort also had been covered up or destroyed by agricultural development.

"Some remains of the wall are still preserved in the forest, but it hadn't been possible to prove that this was indeed a Roman military camp as archaeologists and local historians had long suspected," Hornung said in a statement from JGU.

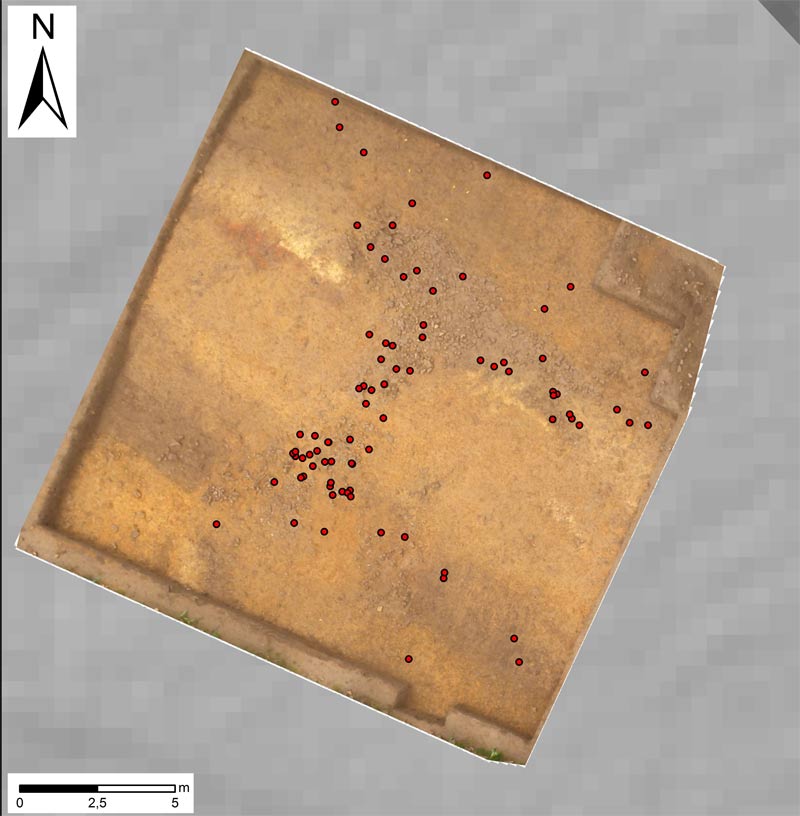

Hornung and her team began work on the site in March 2010, first mapping the fort's dimensions. They found that the military base was made up of a rectangular earthwork enclosure with rounded corners, covering about 45 acres (182,000 square meters). They also found an 18-acre (76,000-square-meter) annex that incorporated a spring, which may have supplied water to the troops.

During excavations the next year, they found one of the gates of the fort, according to a statement from JGU. In the gaps between stones that paved the gateway, the team found shoe nails from the sandals of Roman soldiers and shards of pottery that helped confirm the site's date. The underside of the shoe nails showed a pattern of a cross with four studs, which was typical for that time period. The researchers think the nails, an inch or 2.6 centimeters in diameter, likely loosened from the sandals as soldiers walked along the path.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The most exciting part of our discovery is that it seems possible to link the military camp to an episode of world history by trying to make our dating just a little more precise," Hornung told LiveScience. "It is already highly probable that legionaries were camped there during the Gallic War, but hopefully one day we can tell, whether this happened 53 or rather 51 B.C."

The fort is just 3 miles (5 kilometers) from an Celtic settlement once inhabited by the Treveri tribe. That ancient town had monumental fortifications known as the "Hunnenring" or "Circle of the Huns," but was abandoned around the middle of the first century B.C. The discovery of the nearby Roman fort hints that the Treveri tribe's flight likely was linked to Caesar's troops moving in.

"It is quite possible that Treveran resistance to the Roman conquerors was crushed in a campaign that was launched from this military fortress," Hornung said in a statement.

The findings have been published in the German journal Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to update the fact that the sandal nails were not "tiny" as they'd been described.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus