Yellowstone Wolves Hit by Disease

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Less than two decades after wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park, viral diseases like mange threaten the stability of the new population.

Humans had killed off gray wolves in the region by the 1930s, but in 1995, U.S. wildlife officials tried to restore the native population by bringing 31 wolves captured from Canada into the national park.

The new wolf community initially expanded rapidly, climbing to more than 170 at its peak. But researchers from Penn State University say that the most recent data show the number of animals has dipped below 100.

"We're down to extremely low levels of wolves right now," researcher Emily S. Almberg, a graduate student in ecology, said in a statement. "We're down to [similar numbers as] the early years of reintroduction. So it doesn't look like it's going to be as large and as a stable a population as was maybe initially thought."

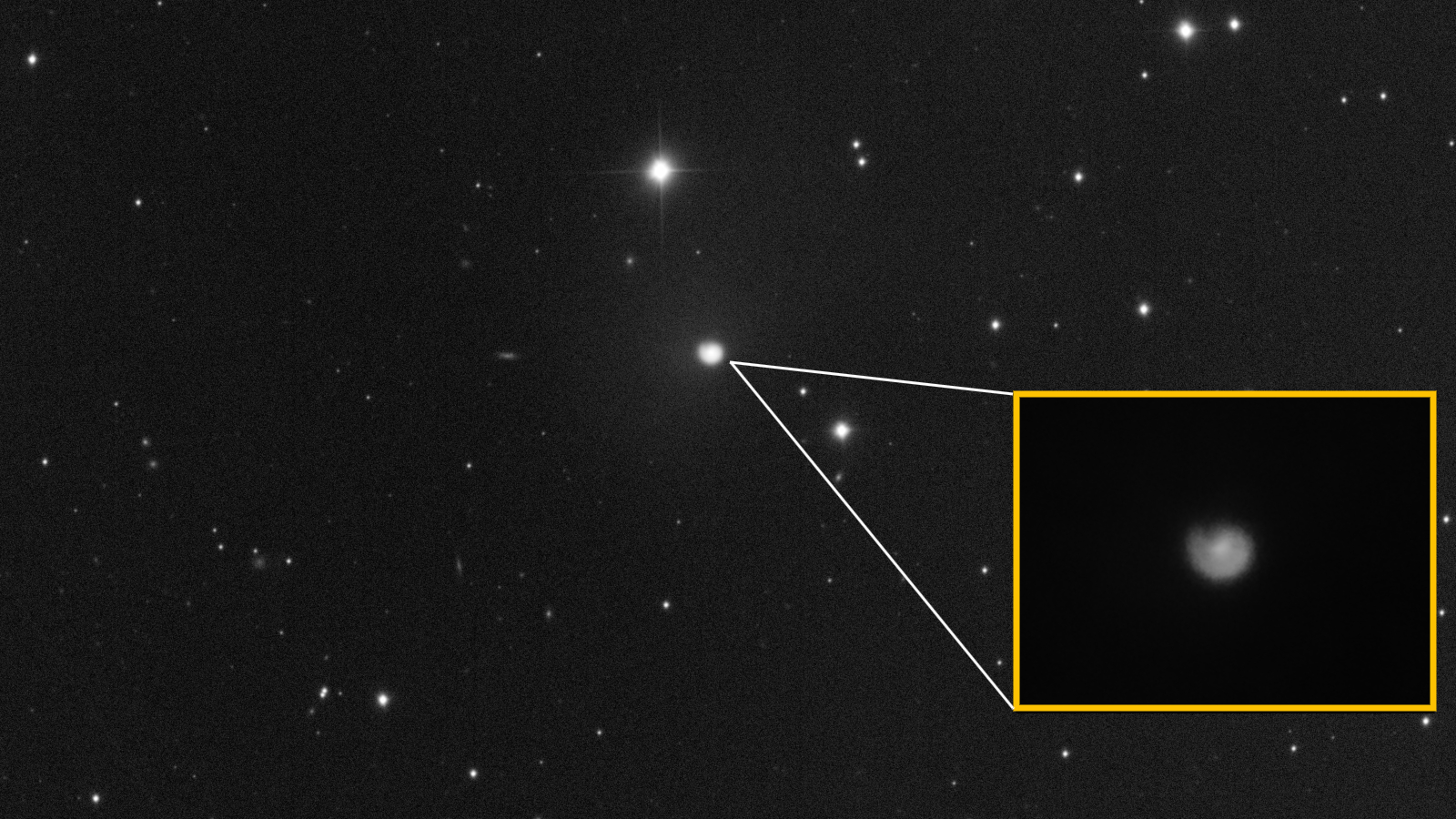

The researchers point to pathogens as the culprit in the population's instability. By 1997, all of the new wolves at the park that were tested for disease had at least one infection, including canine distemper, canine parvovirus and canine herpesvirus. Starting in 2007, wolves inside the park were testing positive for mange — an infection in which mites burrow under the skin causing insatiable scratching and so much hair loss that infected wolves often freeze to death in the winter.

A group of wolves known as Mollie's pack was the first in Yellowstone to show signs of mange, in January 2007, but they recovered from the disease by March 2011. Meanwhile, another group, called the Druid pack — once one of the park's most stable new packs — was decimated by the end of winter 2010 after showing signs of mange just half a year earlier, the researchers said.

"It was in a very short amount of time that the majority of the animals [in Druid] became severely infected," Almberg said in a statement. "The majority of their hair was missing from their bodies and it hit them right in the middle of winter. The summer before it got really bad, we saw that many of the pups had mange."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Penn State researchers found that distance made a difference in the spread of the disease. For every six miles between a pack of mangy wolves and an uninfected pack, there was a 66 percent drop in risk of disease for the healthy pack, the researchers said. Thus the high wolf densities afforded by protection within Yellowstone may come at the cost of some population stability, the researchers wrote in their paper in the current issue of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

Mange was introduced into the Yellowstone ecosystem in 1905 in an attempt to accelerate wolf eradication during an era when wildlife officials tried to cut down predator populations. When the wolves were gone, the disease likely persisted among regional carnivores, like coyotes and foxes, the researchers said.

"Many invasive species flourish because they lack their native predators and pathogens, but in Yellowstone we restored a native predator to an ecosystem that had other canids (animals in the dog family) present that were capable of sustaining a lot of infections in their absence," said Almberg. "It's not terribly surprising that we were able to witness and confirm that there was a relatively short window in which the reintroduced wolves stayed disease-free."

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus