Here's What the Higgs Boson Sounds Like

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Atom-smashing physicists have just turned data for a newly discovered particle, likely the Higgs boson, which is thought to give all other particles their mass, into music.

What does the possible Higgs boson sound like? The music created from the particle's data is beautiful, with one version having a marimba feel. And now, you can listen for yourself.

On July 4, researchers at the world's largest atom smasher, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), in Switzerland, announced they had seen a particle weighing roughly 125 to 126 times the mass of the proton that was consistent with the Higgs boson. The evidence came from two experiments at LHC, called ATLAS and CMS.

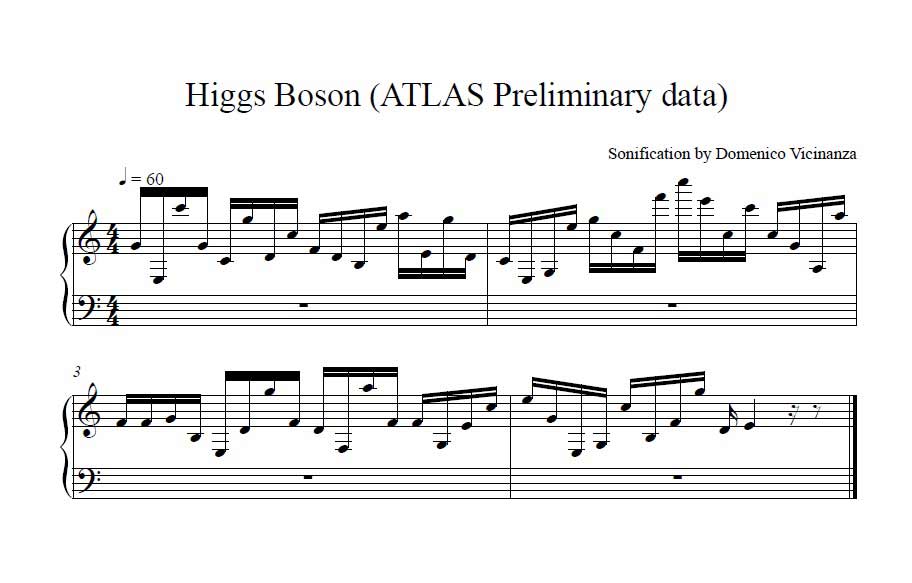

The researchers used so-called data sonification to transform data collected by the ATLAS experiment (one of the two experiments, CMS is the other, that found evidence for the likely Higgs particle) into sound. Essentially, they used a graph showing the ATLAS data and turned the energies of collisions shown on that graph into musical notes. Each data point, or energy number for a collision, was always given the same musical note, with the melody changes following exactly the same profile (the ups and downs) of the scientific data.

"It offers the same qualitative and quantitative information contained in the graph, only translated into notes," composer, physicist and engineer Domenico Vicinanza told LiveScience. [Gallery: Search for the Higgs Boson]

Vicinanza and colleagues created two versions of the "Higgs score," one a piano solo and the other a piano with added bass, percussion, marimba and xylophone. The spike in data around 126 gigaelectron volts (where one GeV is about the mass of a proton), the telltale sign of Higgs, can be heard about 3.5 seconds into these recordings.

The beats are not just music to the ears, as Vicinanza said the melody could be useful for many reasons. "For example, it would allow a blind researcher to understand exactly where the Higgs boson peak is and how big the evidence is," Vicinanza said. "At the same time, it could give a musician the opportunity to explore the fascinating world of the high-energy physics by playing its wonders," added Vicinanza, who is a network engineer at DANTE, which is part of the high-speed pan-European research and education network called GÉANT.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Also, Vicinanza added, using different algorithms for turning data into sound, researchers may be able to detect interesting phenomena just by listening to their data.

Vicinanza and two collaborators, Mariapaola Sorrentino and Giuseppe La Rocca, relied on GÉANT to convert the data into sound.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus