Cosmic Art Glows With Fluorescent Bacteria

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

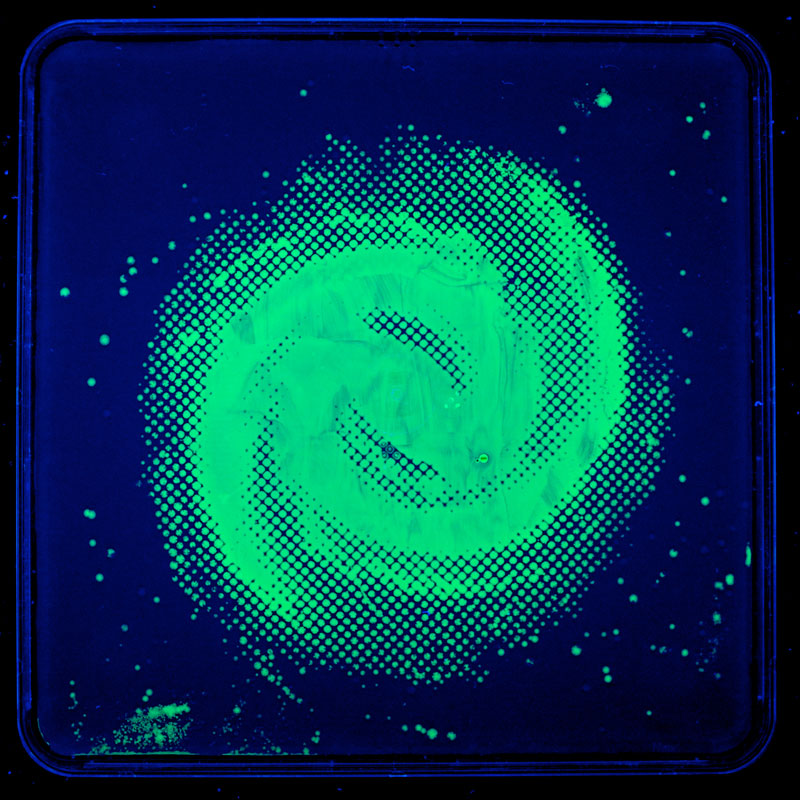

At an upcoming art exhibit, glowing images of heavenly objects — stars, galaxies, nebulae and remnants of supernovae — will have unusual frames: the clear rims of Petri dishes, the sort typically used to grow microbes.

There's no coincidence here. The images of these astronomical structures have been created from the bacterium E. coli, a more typical resident of the cell culture dishes.

The artist behind these new images, Zachary Copfer, a graduate student at the University of Cincinnati, knew he wanted to create something that reflected the concept of "star stuff." Introduced by writer and astronomist Carl Sagan, "star stuff" refers to the concept that living things, including humans, are made up of atoms created in stars.

"I realized when I looked through the microscope, it looks pretty similar to when I look through the telescope," Copfer told LiveScience.

His work, made as part of his master's of fine arts degree, is scheduled to go on display at the Sycamore Street Gallery in downtown Cincinnati, along with work by other students on June 8 through 12. [Gallery: Microbes Make Galaxies]

Small meets large

To bring the very large and the very small together, Copfer, a former microbiologist, developed a new photographic printing technique he calls bacteriography.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

First, he genetically alters his medium, the bacteria, by giving them a sequence of genes, originally found in jellyfish, that code for a fluorescent protein (called GFP for green fluorescent protein). Under ultraviolet light (also called a black light), this protein emits light at a longer wavelength that is visible to the human eye.

He then spreads the genetically modified microbes within a Petri dish and exposes them to short-wavelength ultraviolet radiation. This treatment is not intended to make them glow; it kills off the microbes living in certain patches. Later, these patches will become the dark spots of the image. He then gives the bacteria some time to grow and spread, until he is satisfied with the image. To stop the growth where it is, he refrigerates the dish, gives it another radiation treatment and covers the bacteria up with a layer of acrylic. Then the image is ready to be displayed.

"It's totally in its infancy as far as I am concerned," he said. "This is literally the first step of making work using this method and exploring a new medium."

Art and science

Copfer has also used a variation on this technique to use red-colored bacterium Serratia marcescens to create portraits of artists and scientists who have inspired him. He plays with the relationship between the two fields by labeling scientists Albert Einstein and Charles Darwin as his favorite artists, and artists like Pablo Picasso and Leonardo da Vinci as his favorite scientists.

"Picasso and Einstein were working with the same idea, looking at three-dimensional space from different perspectives, Einstein from the Theory of Relativity and Picasso with cubism," Copfer said.

In future work, he hopes to explore the fraught relationship people have with bacteria, which becomes evident when they look at his work.

"People love to get in close to look at it, and when I tell them what it is, they step back, like, 'oh my God, I shouldn't be near this," he said.

The gallery is located in the Sycamore Place Lofts at 634 Sycamore St., Cincinnati.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus