Amazing Images Reveal the Art of Science

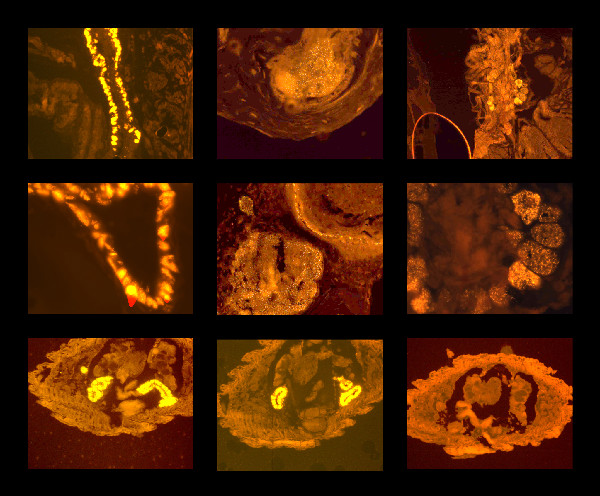

NEW YORK — Some species of bacteria live inside leeches, providing their hosts with nutrients. The relationship between these two creatures roused the artistic side of two scientists. Two American Museum of Natural History curators added fluorescent molecules to DNA designed to pair up with the bacterial DNA, and that allowed them to create pictures of bacteria inside adult and juvenile leeches. Some of the bacteria are visible as tiny gold specks.

Nine of the pictures are on display as part of a new, yearlong exhibit at the natural history museum that explores the artistry of scientific images. [See the amazing science images] “When you first look at it, it’s really quite abstract," said Mark Siddall, curator of invertebrate zoology at the museum, who with associate curator Susan Perkins created the leech with bacteria images. "I thought this might be something that other people might like to engage with."

The artistic side of science

The exhibit, "Picturing Science: Museum Scientists and Imaging Technologies," draws from a wide range of research currently under way at the museum. It includes: an Andy Warhol-style analysis of a meteorite's chemical composition, a bird's-eye view of the Messier 101 galaxy pieced together from images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, elegant black-and-white images of insect genitalia, and ritual objects stashed within a Tibetan wood figure. Color, form and spatial relationships are typically the domain of an artist, but scientists will use these characteristics to explore scientific questions, Siddall said. Their methods can be fairly low-tech. Three species of fish were still whole when images were made of their insides, but the bones and cartilage stand out sharply thanks to the use of dyes and chemicals to make the other tissues transparent. And an arachnologist needed only ultraviolet light to make ghostly images of scorpions. Highly sophisticated techniques are also represented. A mathematical simulation of how gas behaves after a star explodes as a supernova generated an image of the orange flames of interstellar gas. The colorful meteorite slices and the insect genitals were both created by bombarding the specimens with electrons (the negatively charged particles in atoms) under sophisticated microscopes. Looking inside a lizard

Edward Stanley, a doctoral candidate in comparative biology at the museum’s Richard Gilder Graduate School, uses computed tomography (CT) scans to look at evolutionary patterns within a family of lizards. His contribution to the exhibit shows the white skeleton of an Armadillo lizard, a native of southern Africa, which bites its tail and rolls into a ball to protect its soft belly while exposing its bony plates to predators. These plates appear as semi-transparent, leafy green scales covering the back of its body, limbs, head and tail. So why not just dissect the lizard or remove the rest of its tissue to look at these bones? "That's a destructive method, and the museum has a finite number of specimens," Stanley said. "This way we get all the information out without having to destroy the armor." Removing skin, muscle and other tissue would destroy the arrangement of the bony plates, an important part of Stanley's research on the evolutionary history of this species and its relatives. CT scans, also used in medicine, employ X-rays to create three-dimensional images. Because they can visualize the interior of an object, a CT scan makes it possible for scientists to avoid damaging a specimen, in this case a preserved lizard. CT scans have other advantages: They are quick, easy and provide additional data, like the volume of individual bones, Stanley explained. The exhibit is on display at the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan until next June.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.