Stem Cells Carry 'Suicide Pills' for Instant Death

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Embryonic stem cells — those revered cells that give rise to every cell type in the body — will swiftly fall on their metaphorical swords for the greater good if they are injured, new research suggests.

Embryonic stem cells are special because they can give rise to any tissue in the body. Learning more about these cells could help researchers make specific cell types. Specifically, the lab is studying how to grow neurons to treat Parkinson's.

Most research on embryonic stem cells has focused on how to grow them into different cell types in the lab, with studies of the cells themselves lacking, the researchers said. Limitations on government funding of human embryonic stem cell labs have also hampered work in this area.

Deshmukh and colleagues treated human embryonic stem cells with DNA-damaging drugs to see what happened. Almost all of the cells committed suicide within five hours, suggesting these types of cells are more sensitive to damage than other cell types, which usually take 24 hours to die once they get damaged.

"Mutations that develop in these cells could be catastrophic for the developing organism, so it would make sense for these cells to be rapidly eliminated," Deshmukh said. This quick-draw death switch is only present for a few days in a stem cell's life, though. Once the cells start down paths to become specific body parts, they deactivate their instant-suicide pathway.

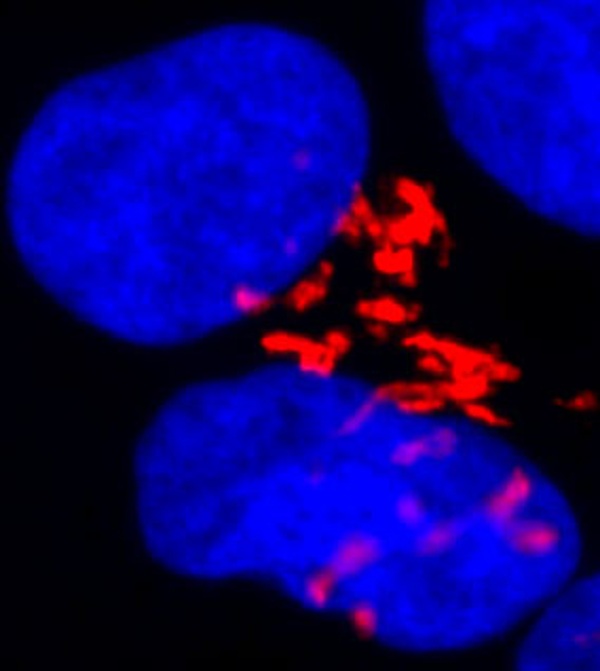

The embryonic cells keep this molecular kill switch, called Bax waiting, around for this very purpose, the researchers found. Instead of activating Bax at the end of a long chain reaction, the embryonic stem cells have it ready and waiting in case of DNA damage.

"What these cells do is very clever," said Deshmukh. "They have activated Bax, but they've also parked it in a safe little compartment." When released, Bax shuts down the cell's power plant, the mitochondria, effectively choking off the cell's energy source.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This cell suicide is critical not only for development (without it, we wouldn't have normal fingers and toes), but also to help stop the spread of disease. "Injured" cells with damaged DNA can lead to mutations that could kill an organism. In this way, a damaged cell is dangerous to its fellow embryonic cells. If the organism dies, so do all of its cells.

The study was published today (May 3) in the journal Molecular Cell.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter, on Google+ or on Facebook. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus