New Test Reveals Good vs. Bad Sperm

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A simple laboratory test can separate healthy, functional sperm cells from sperm with damaged DNA with 99-percent accuracy, according to new research.

The test uses a chemical found in the membrane of human egg cells to sort functional from non-functional sperm. It has already been approved for use in in-vitro fertilization by the Food and Drug Administration and can raise the chances of a successful pregnancy by 20 to 30 percent, according to lead developer Gabor Huszar, a senior researcher in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at Yale Medical School.

Traditional male fertility tests focus on sperm count (how many sperm are present) and how mobile they are. In natural fertilization, Huszar said, both the sperm and egg develop structures on their surfaces called receptors that are necessary for successful bonding.

"The sperm and the egg choose each other," he said.

But in some new IVF methods, doctors choose the sperm, injecting a single sperm cell into an egg under a microscope. Simply looking at sperm count and average motility can't tell doctors which individual sperm have undamaged DNA and have a good chance of fertilizing an egg. Inadvertently injecting low-quality sperm could lead to failed fertilization. Even if fertilization is successful, the genetic problems carried by the sperm could lead to developmental problems and miscarriage.

To sort the wheat from the chaff, Huszar and his team use a compound called hyaluronic acid. The acid is an important component of the membrane surrounding human egg cells, and sperm are drawn to bind with it, though not all are successful.

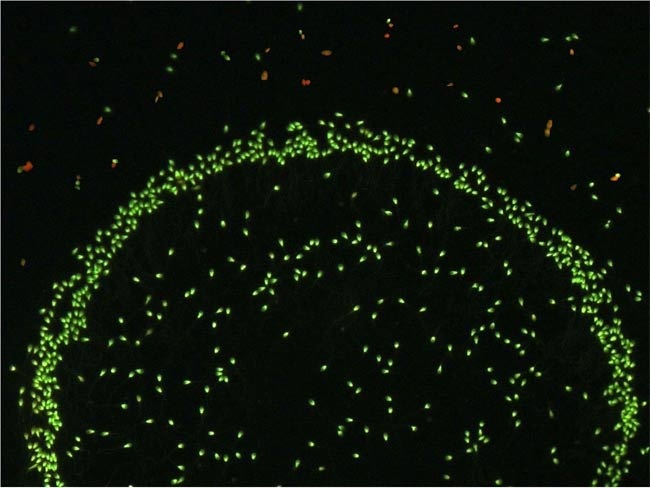

To find out if the strong-binding sperm were also the most genetically fit, the researchers treated sperm samples from 50 men with hyaluronic acid and stained the sperm cells with a solution that turns intact DNA green and damaged DNA red.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After 15 minutes, the researchers gently separated the bound sperm from the unbound. The results were striking: More than 99 percent of the sperm that had bonded with egg cells were stained green, compared with just half of the unbound sperm.

That means the sperm that bound to the hyaluronic acid were high-quality - as high-quality as the sperm selected by human egg cells during natural fertilization, Huszar said.

"This tells us that this device, which we developed for sperm selection, works excellently," he said.

The method is already used in some fertility clinics to choose sperm for IVF treatments, said embryologist Zsolt Nagy, the lab and scientific director at Reproductive Biology Associates in Atlanta, who was not involved in the study. Hyaluronic acid testing can also be used to diagnose infertility by checking how many of a man's sperm are capable of binding and fertilization.

"It is a technology that I would expect to spread out in most IVF centers," Nagy said.

The study is published in the June/July issue of the Journal of Andrology.

- 10 Surprising Sex Statistics

- 5 Myths About Women's Bodies

- The Future of Baby-Making

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus