Van Gogh's Sunflowers Are Mutants

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

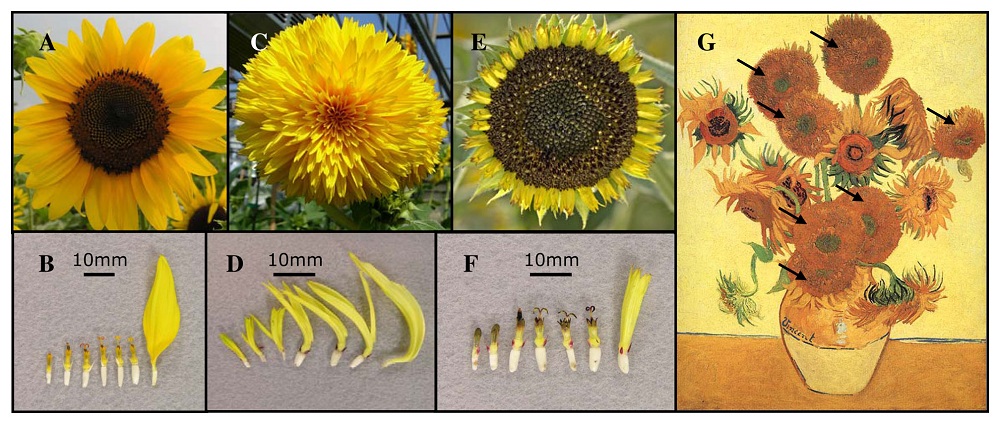

The whimsical appearance of some of the sunflowers in Vincent van Gogh's paintings isn't the result of the painter's alleged mental illness. Researchers have found that overly-bushy sunflowers are actually the result of a genetic mutation in some strains of the flowers.

The typical sunflower has a brown, seed-filled middle and a ring of yellow petals, but some seem overgrown with petals in "double rows" — like one variety called the "Teddy Bear" — and others have scrawny petals and seeds extending nearly to the edge of the flower. The researchers discovered that a genetic mutation is to blame for these differences.

"In addition to being of interest from a historical perspective, this finding gives us insight into the molecular basis of an economically important trait," study researcher John Burke, at the University of Georgia, said in a statement. "You often see ornamental varieties similar to the ones Van Gogh painted growing in people's gardens or used for cut flowers, and there is a major market for them."

Sunflower heads — actually multiple small flowers called florets — have a very specific symmetry. The "seeds" are laid out in a special geometric pattern. In a normal sunflower, the outer florets sprout into petals and the inner ones mature into seeds. [See more images of sunflower varieties]

To double-check their results, they sequenced this gene and looked for it in several commercially available types of sunflowers. They never saw the mutation in flowers that had the traditional sunflower appearance, but always saw it in the fluffy varieties.

The newly discovered mutation changes how the plant regulates where the line between "petals" and "seeds" is drawn. When mutated, the gene can move this boundary either closer to the center of the flower head or farther away from it and closer to the outer layers of florets.

If the boundary line moves toward the center, the flower loses the traditional "sunflower" appearance and looks more like the "Teddy Bear" sunflower. If it moves outward, the flower has more seeds and a dinky layer of petals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"All of this evidence tells us that the mutation we've identified is the same one that Van Gogh captured in the 1800s," Burke said.

The study was published today (March 29) in the journal PLoS Genetics.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus