Unrequited Love? 16th-Century Erotic Poem Discovered

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

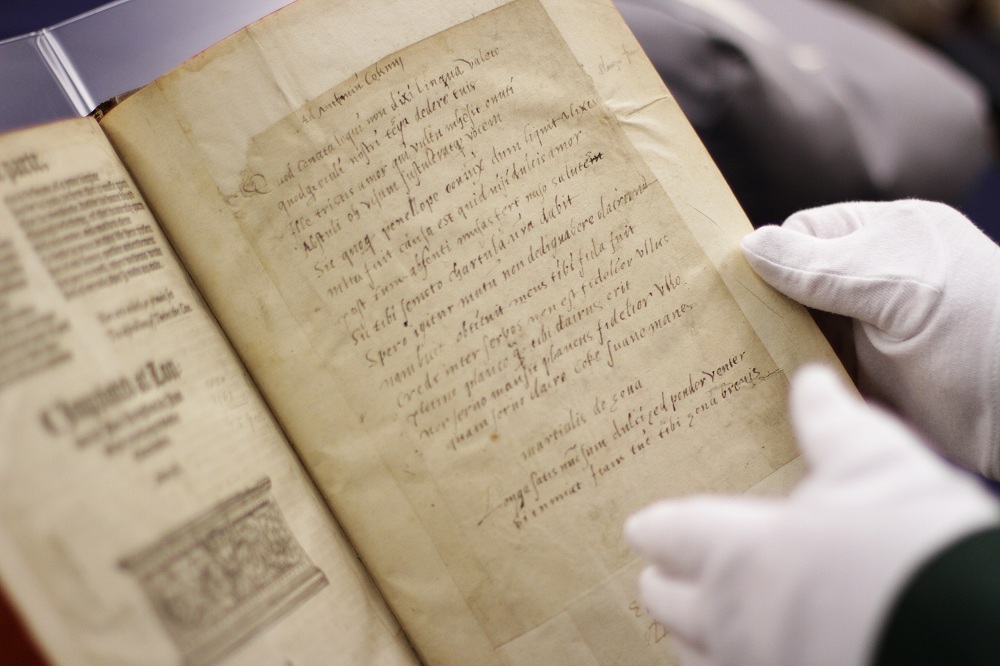

Nearly 450 years ago, when England was tearing itself apart over religion, a Catholic woman named Lady Elizabeth Dacre wrote an elegant but at times erotic Latin love poem to Sir Anthony Cooke, a Protestant and tutor to King Edward VI, the successor of Henry VIII.

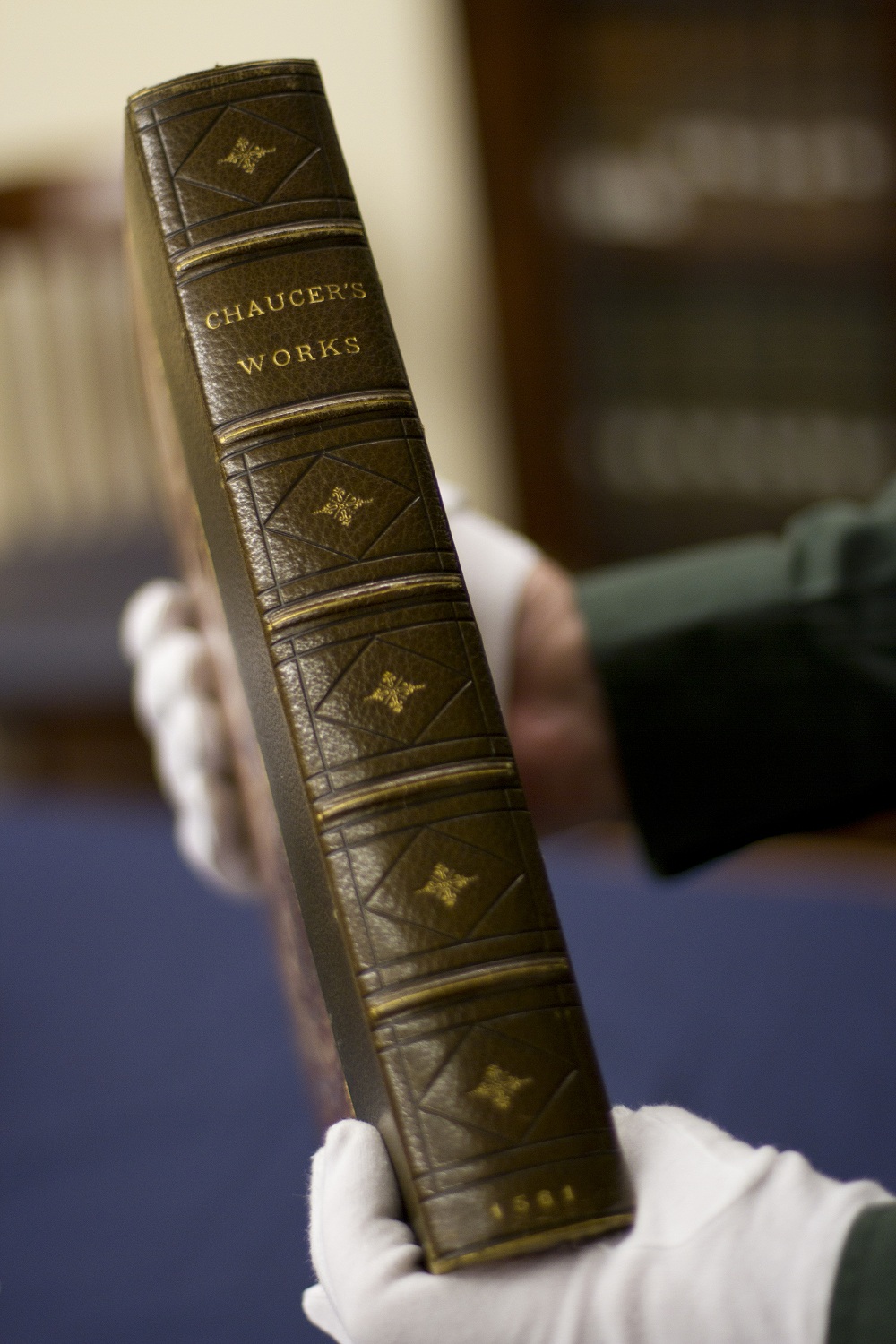

That poem was rediscovered recently in the West Virginia University library, inside a 1561 copy of Chaucer. It hints at a love affair that was not to be.

"It's a very beautiful piece and I think for her it was quite a prized possession, because it's been so very carefully copied out and looked after," Elaine Treharne, a professor at Florida State University, told LiveScience.

While a visiting professor at the university, Treharne discovered the love poem in the library's rare-book collection inside the cover of the Chaucer book. Working with colleagues she translated it from Latin and confirmed Elizabeth Dacre as its author. Her analysis, which will be detailed in an upcoming issue of the journal Renaissance Studies, also suggests Dacre wrote the poem in the 1550s or 1560s. [6 Most Tragic Love Stories in History]

Love translated

The first part of the poem, as translated by Treharne, seems to refer to a period in 1553 when Cooke, under the reign of Mary I, was sent to the Tower of London and then exiled. It reads:

"The goodbye I tried to speak but could not utter with my tongue by my eyes I delivered back to yours. That sad love that haunts the countenance in parting contained the voice that I concealed from display, just as Penelope, when her husband Ulysses was present, was speechless – the reason is that sweet love of a gaze ..."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The erotic ending of the poem quotes a Roman writer named Martial:

"Long enough am I now; but if your shape should swell under its grateful burden, then shall I become to you a narrow girdle."

While Cooke would almost certainly have seen the poem, Treharneisn't certain that there actually was a romance between the two.

"It might represent some kind of love affair, [or] it might be a more academic exercise, it's very difficult to determine," Treharne said. "If it was a rhetorical exercise I wonder why she kept it."

A love story behind the poem?

Dacre was born as Elizabeth Leybourne, in 1536, according to historical sources. And so at the time Cooke went into exile in 1553 she would have been 17 years old and he well into his 40s. Cooke's wife, Anne, died in that same year. It's possible that Cooke tutored the unmarried Elizabeth, Treharne said.

"If this affair occurred, it might have taken place, perhaps at court, around 1553, at which time Cooke left for the Continent for five years, his own wife Anne having died in that same year," Treharne writes in the journal article.

In 1555, while Cooke was in exile and Mary I was on the throne, Elizabeth married Thomas Dacre, an English baron. The fact that she refers to herself as a "Dacre" in the poem suggests that she composed it sometime after she was married.

A Tudor power couple

In November 1558, Queen Elizabeth I, a Protestant, ascended to the throne. Cooke returned from exile, a widower. At this point Dacre was married with children.

The only opportunity Elizabeth would have had to get together with Cooke, without divorcing Thomas, would have been in 1566 when the Baron died. However, this never happened and mere months after the Baron's death the widowed Dacre married Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk and a Protestant himself. [The Most Powerful Women Leaders]

"I think it was a political move, that that marriage was a very political undertaking," Treharne said. Dacre had a considerable amount of land, as did the Duke. "Marrying the Duke of Norfolk and consolidating all that land would have been the most judicious thing to do."

It was a union that made her powerful as well. "At one point she was probably the next-most-powerful woman in the kingdom, after the Queen," said Treharne.

But while she had power she may not have had love. She died while giving birth in 1567. A book published in 1857 by a latter Duke of Norfolk suggested that when she was dying she was not allowed to see a Catholic priest, something which Treharne calls an act of "cruelty."

"the Duchesse . . . desir’d to have been reconciled by a Priest, who for that end was conducted into the garden, yet could not have access unto her, either by reason of the Duke’s vigilance to hinder it, or at least of his continual presence in the chamber at that time." (From the book "The lives of Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel and of Anne Dacres, his Wife," published in 1857)

As for Sir Cooke, he never remarried, and died in 1576, at more-than-70 years of age. A statue was erected in his memory.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus