History Vanishes with Melting Himalayan Glacier

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

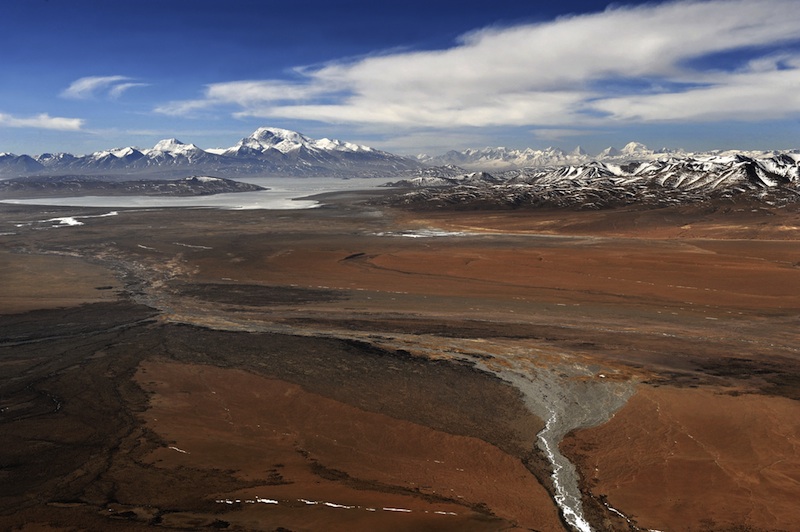

SAN FRANCISCO — A half-century record of history has melted away from the Naimona'nyi glacier in southwestern Tibet, highlighting the changes coming to glaciers across the Himalayas.

Ice cores from glaciers capture a detailed history of the atmosphere and climate from the time when the snow and ice fell. They record dust, ash and even minute amounts of nuclear fallout from atmospheric nuclear tests conducted in the 1950s. It can all be seen in ice around the globe, from the Himalayas to the poles to the Alps.

But at Naimona'nyi, that evidence has all but disappeared.

"At least the top 50 years of this record has been obliterated," Mary Davis, an ice-core researcher at Ohio State University, reported here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU). "We surmise that perhaps it is gone because of melting."

That melting is attributable to climate change, scientists say. According to Duncan Quincey, a glacier researcher at Aberystwyth University in the United Kingdom, eastern Himalayas glaciers are in an accelerating retreat, while a small number of western Himalayas glaciers are expanding, driven by different weather patterns in those areas.

By drilling tubular cores out of glaciers and ice caps around the world, glaciologists can track climate history and even pinpoint specific human events such as the 1950s and 1960s nuclear bomb tests in the South Pacific. [History's Greatest Explosions]

At Naimona'nyi glacier, that recent historical record has vanished, Davis said. Meanwhile, she said, the glacier is showing ominous signs of melt, including standing water in ponds on top of the glacier and small cylindrical melt-holes, called "cryoconites," in the ice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The glacier is losing mass from the top through melting, but it's also retreating," Davis said. "This retreat is accelerating."

Glacial retreat, which occurs as the ice melts along its edges and so "moves" landward, could cause water shortages among the people who depend on these rivers of ice as local sources of drinking water, Davis said. Retreating glaciers can also leave behind large glacial lakes, according to Quincey. These lakes are at risk of bursting from their earthen-dam walls, causing devastating flash floods in valleys below.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus