New Theory Explains What Makes YouTube Videos Go Viral

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

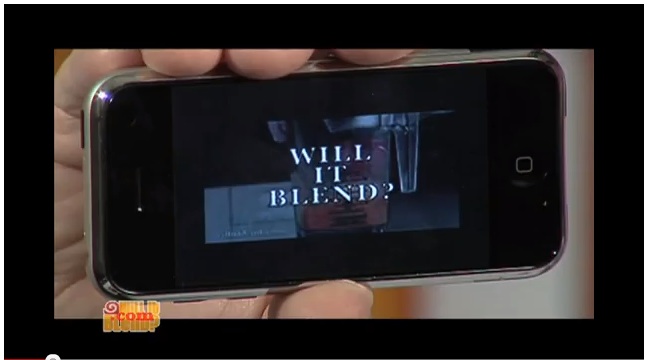

More than 10 million people have watched a YouTube video of an iPhone being pulverized in a blender. It's actually a commercial for Blendtec — a company most viewers had probably never heard of. But with the viral clip, Blendtec let social networking spread its name and message rather than paying for a mass advertising campaign. And it worked like a charm.

"Viral-produced movies" are the new holy grail of advertising, but they're tough to pull off. Only the fittest among them can overcome the slight annoyance people feel when they realize a video they enjoyed was actually an ad — and yet compel them to share it with friends anyway. As Brent Coker, a marketing professor at the University of Melbourne in Australia, says, "Ensuring the success of a viral-produced movie is still largely hit-and-miss … babies, pranks, and stunts seem to have great success on some occasions, but turn into catastrophic failures on others." [See video examples]

So what defines a great ad — one that a viewer will choose to post to Facebook?

Coker has come up with a recipe for success called the branded viral movie predictor algorithm. According to the algorithm, the four ingredients required for a video to go viral are congruency, emotive strength, network involvement, and something called "paired meme synergy."

First, the themes of a video must be congruent with people's pre-existing knowledge of the brand it is advertising. "For example, Harley Davidson for most people is associated with Freedom, Muscle, Tattoos, and Membership," Coker explained on his website. Videos that strengthen that association meet with approval, "but as soon as we witness associations with the brand that are inconsistent with our brand knowledge, we feel tension." In the latter case, few people will share the video, and it will quickly "go extinct."

Second, only viral-produced videos with strong emotional appeal make the cut, and the more extreme the emotions, the better. Happy and funny videos don't tend to fare as well as scary or disgusting ones, Coker said. [What Is the Most Disgusting Thing In the World?]

Third, videos must be relevant to a large network of people — college students or office workers, for example.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And last, Coker came up with 16 concepts — known on the Internet as "memes" — that viral-produced videos tend to have, and discovered that videos only go viral if they have the right pairings of these concepts. "When combined, some combinations appear to work better together than others," he told Life's Little Mysteries.

For example, the concept he calls Voyeur, which is when a video appears to be someone's mobile phone footage, works well when combined with Eyes Surprise — unexpectedness. These also work well in combination with Simulation Trigger, which is when "the viewer imagines themselves being friends [with the people in the video] and sharing the same ideals," he said.

According to Coker, one viral video that used all three of those memes — and exemplified the other BVMP strategies, too — was a 2007 ad by Quiksilver, the beach apparel company. The grainy footage showed surfers throwing dynamite in a river and surfing on the resulting waves. It quickly topped 1 million views.

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus