Could Blasts from Cosmic Collisions Destroy Life on Earth?

The persistence of life on Earth may depend on massive explosions on the other side of the galaxy, according to a new theory that suggests powerful bursts of space radiation could have played a part in some of our planet's major extinction events.

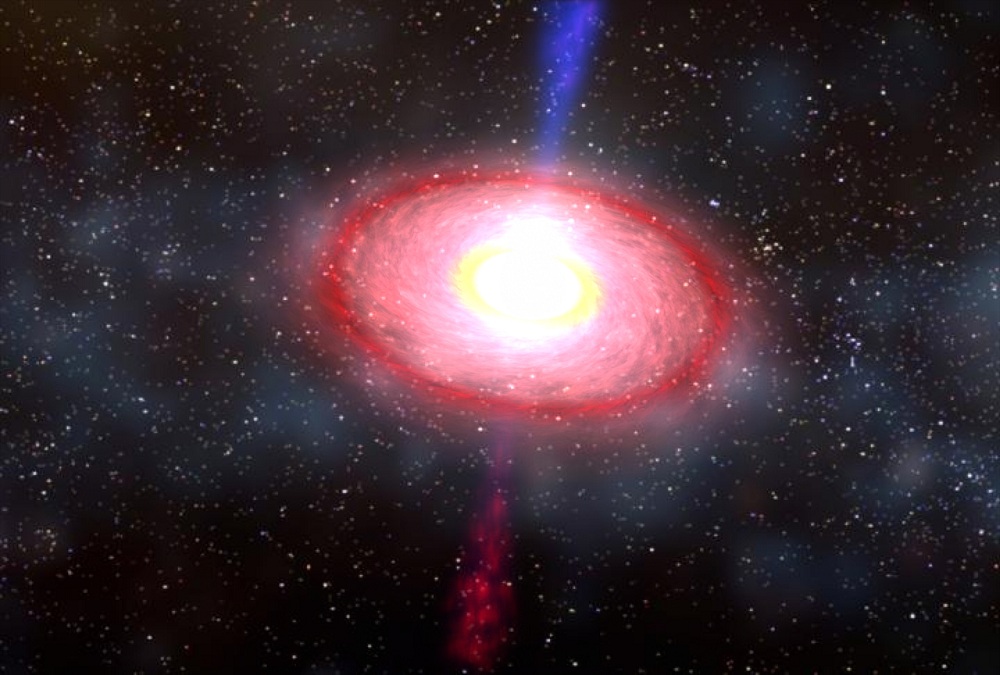

The explosions — gamma-ray bursts thought to occur when two stars collide — can release tons of high-energy gamma-ray radiation into space. The researchers found that such blasts could be contributing to the depletion of the Earth's ozone layer. Disruption of the ozone layer lets ultraviolet light filter down to the surface of the Earth, where it can change organisms by mutating their genes.

Now, researchers are beginning to connect the timing of these gamma-ray bursts to extinctions on Earth that can be dated through the fossil record.

"We find that a kind of gamma-ray burst — a short gamma-ray burst — is probably more significant than a longer gamma-ray burst," study researcher Brian Thomas of Washburn University, in Topeka, Kansas, said in a statement. "The duration is not as important as the amount of radiation." [Top 10 Strangest Things in Space]

The research will be presented Sunday (Oct. 9) at the Geological Society of America's annual meeting in Minneapolis.

Bursting out

Gamma-ray bursts come in two flavors: a longer, brighter burst and a "short-hard" burst, which lasts less than a second but seems to give off more radiation than a longer burst.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If such a burst were to happen inside the Milky Way, its effects on Earth would be much longer lasting. These bursts of radiation reach the Earth's atmosphere and cause free oxygen and nitrogen atoms to bang together, and some recombine into ozone-destroying compounds called nitrous oxides. Nitrous oxides in the atmosphere are long-lived; they keep destroying ozone until they fall out of the sky in rain drops.

The short bursts may be caused by fender-benders between stars, such as dense neutron stars or black holes colliding. The researchers were able to estimate that such stellar collisions probably happen about once every 100 million years in any given galaxy. At this rate, Earth would have been hit by several of these short-hard events over the course of its 4.5-billion-year history.

Life on Earth

Destruction of the ozone layer can have many effects on life on our planet. Radiation blasts on the world's plants and animals could wreak havoc on Earth's food webs and possibly lead to planetwide extinction events.

Improved and accumulated data collected by NASA's SWIFT satellite, which catches gamma-ray bursts in action in other galaxies, is providing a better case for the power and threat of the short bursts to life on Earth. Researchers are also looking for evidence of past bursts, including special elements that are created only during radiation events hitting Earth, such as a heavy version of iron.

Thomas is now working with paleontologists to correlate levels of this heavy iron with evidence of extinction events in the fossil records.

"I work with some paleontologists, and we try to look for correlations with extinctions, but they are skeptical," Thomas said. "So if you go and give a talk to paleontologists, they are not quite into it. But to astrophysicists, it seems pretty plausible."

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.