Fashion Forward: How Some Insects Grew Strange Helmets

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

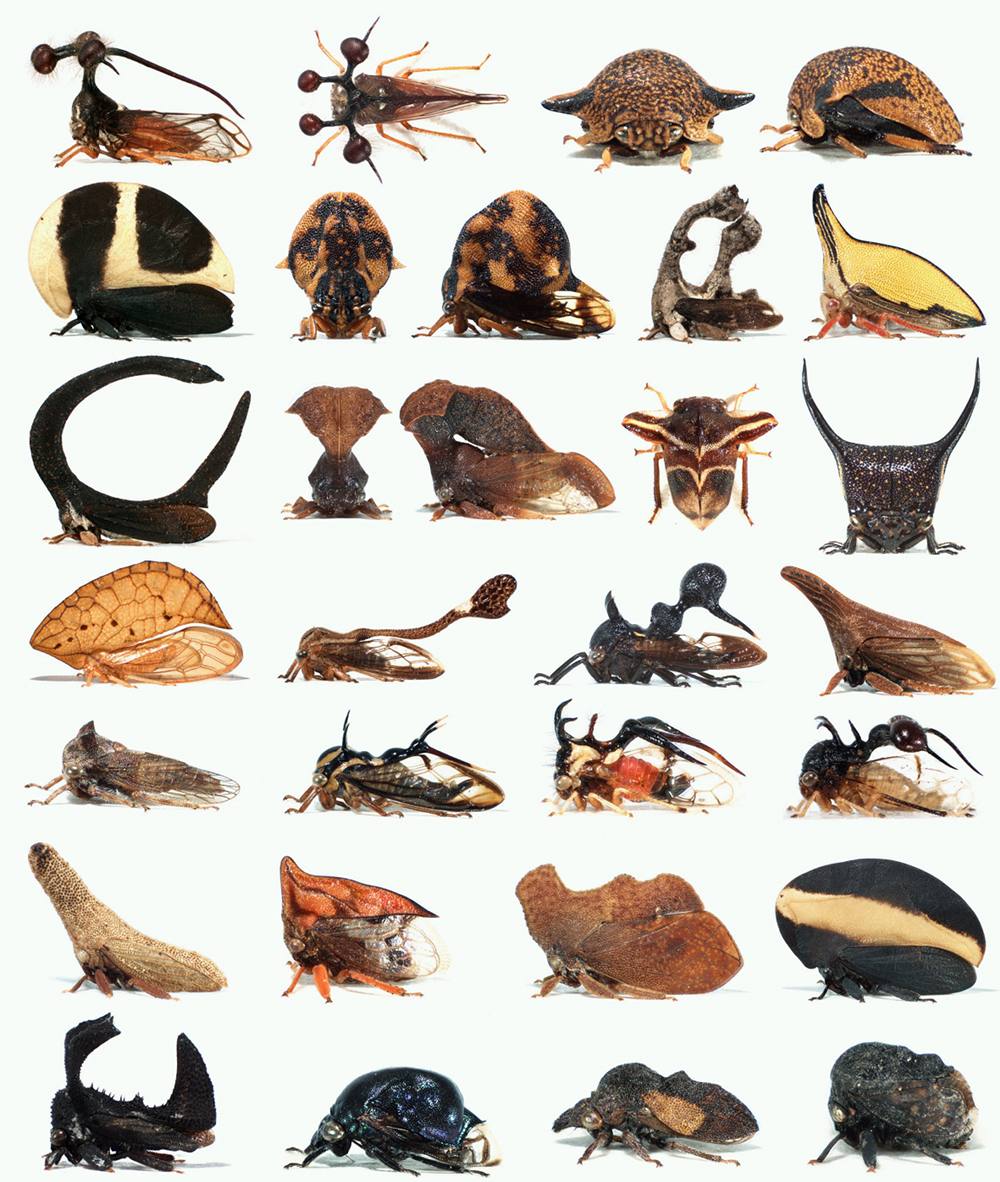

Tiny insects called treehoppers sport some very odd helmets. Now, researchers have found the insects developed this headgear by reactivating and repurposing their wing-making machinery.

"We think this is an example of how evolution can work at a morphological level, by recycling a genetic program by expressing it in a new location on the body," said study researcher Benjamin Prud'homme, of the Institut de Biologie du Développement de Marseille-Luminy, in France. "It was the raw material for evolution to play with, to evolve into new shapes." [Image of helmeted insects]

Researchers hypothesize that the treehoppers, which emerged on Earth about 40 million years ago, use their headgear for camouflage. Some of it resembles debris or animal droppings, and one species even dons headgear that looks like an aggressive ant.

"We don't know the function of the helmet," Prud'homme told LiveScience. "To human eyes, they look like they mimic the environment in which the animal lives."

Helmet head

The researchers studied the genes involved in the development of both wings and helmets, finding similarities. The same genes expressed in other thoracic segments during wing development are expressed during helmet development in the first thoracic segment (just behind the head).

"It is quite remarkable — the helmets look very different from wings," Prud'homme said. "In fact, they aren't wings per se; they aren't used in flight."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Genes are expressed in all insects that normally stop development of wings (and other winglike features, such as the treehopper's helmet) in the first thoracic segment. In the treehopper, these genes are still active and expressed, so some other part of the wing-formation pathway must be defective, allowing the treehoppers to grow their helmets.

Body-building

To fashion their helmets, the treehoppers had to first turn this wing-making machinery on in that body segment, after being unused for 250 million years. "It's a unique situation in winged insects," Prud'homme said.

Insect wings first appeared about 350 million years ago in primitive winged insects, which had wings on every segment. Over the next 100 million years, these wings were corralled into just the second and third thoracic segments and have stayed that way ever since.

Adding features to the insect body plan — the general blueprint of body parts on which all insects develop — is a very rare event. Gradually, some insects have lost wings all together, though losing features is much less complicated than adding them.

"We understand how things can be removed, but don't understand how novel features can be added," Prud'homme said. "This is much more gray area of our understanding."

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus