Clutter Increases Stereotyping and Discrimination

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This article was updated at 10:20 AM ET on Nov. 2, 2011.

Editor's Note: Due to an ongoing investigation into the credibility of Diederik Stapel's research conducted at Tilburg University, the University of Groningen and the University of Amsterdam, the journal Science has issued an "Editorial Expression of Concern" about the validity of the work detailed in this article and its conclusions. Stapel has been suspended after admitting to University officials that some of his papers contain falsified data.

A messy or chaotic environment causes people to stereotype others, probably out of a need to control and organize the situation around them, new research suggests.

"We are very dependent on the physical environment much more so than we think we are," said study researcher Siegwart Lindenberg, of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. "Imagine people have to live their whole lives in neighborhoods in this condition; they have a much more difficult time not to stereotype."

Stereotyping is much simpler than reality, allowing us to place people into clear-cut categories. In this way, stereotyping is a way to cope with chaos, acting as a mental cleaning device in the face of disorder. And while ordering thoughts isn't problematic, Lindenberg has shown that this thought process actually manifests itself in discriminatory behavior.

Previous studies by Lindenberg's team have found that this kind of physical disorder, such as broken windows in abandoned houses, graffiti and litter, can lead people to ignore social norms and increase theft, littering and trespassing.

Disordered norms

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers tested how white participants in messy and disordered situations reacted when presented with the opportunity for stereotyping. In the first tests, volunteers in a train station filled out the survey on a bench with another person sitting nearby. Half of the tests were done when the station was clean and the other half when it was dirty, during a cleaner's strike.

When the station was dirty, participants sat about a chair's distance farther from a black participant than from a white one, and they chose more stereotypical answers in the survey. "In the station, people filled in questionnaires about Muslims, homosexuals and the Dutch, and yet their behavior was directed toward blacks," Lindenberg said. "Their way of processing information in general turns toward simplicity, toward black and white."

Similar results were seen in an area of an affluent neighborhood, where the street was either clean or featured a tipped-over bicycle next to a ripped-up sidewalk and a car parked on the curb. Passers-by filled out the questionnaire and got 5 euros (about $7) in small change as payment. When asked to donate to a minority-improvement fund, people on the disorderly street donated about 65 eurocents (or $1) less than those on the orderly street.

Messy manifestations

The researchers then took their testing into the lab. They showed participants pictures of messy or ordered bookcases and rooms, or neutral images, then asked them questions about their underlying need for order, and gave them the survey on stereotypes. People who indicated a higher need for order also stereotyped more in response to the disordered pictures.

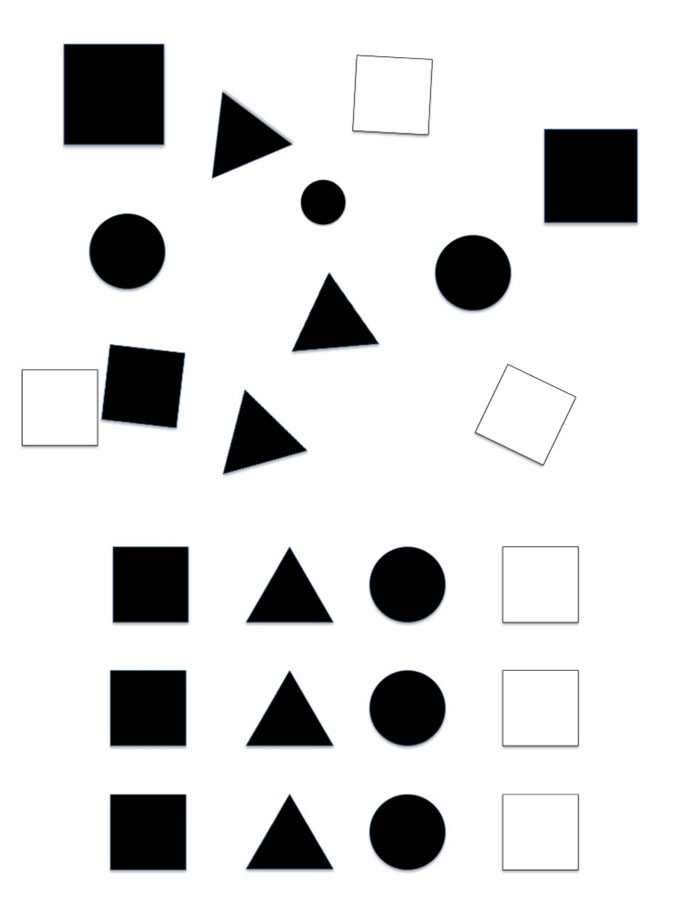

If this need for order is what caused the stereotyping, the research team reasoned, then giving the participants a way to vent that stereotyping should reduce their need for control. After observing an ordered or disordered picture of abstract shapes (circles and triangles), participants were given the stereotyping questionnaire or an unrelated task.

"Even though circles and triangles don't mean anything in daily life, it still had that effect," Lindenberg said, suggesting it was the presence of disorder, and not some other factor, that caused the stereotyping.

And the participants who had stereotyped after seeing the disordered pictures also demonstrated a lower need for structure than those who had completed the filler task, suggesting that stereotype behavior was a way to bring order to their world.

"One way to fight unwanted stereotyping and discrimination is to diagnose environmental disorder early and to intervene immediately," Lindenberg and co-author Diederik Stapel conclude in the paper, published today (April 7) in the journal Science. "Signs of disorder such as broken windows, graffiti, and scattered litter will not only increase antisocial behavior, they will also automatically lead to stereotyping and discrimination."

"The most important use of the information is of course for communities, for authorities in communities, to clean up," Lindenberg told LiveScience.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus