Scientists Eye Benefits of Spinach

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In the wake of the E. coli outbreak in which dozens of Americans were poisoned by tainted spinach, consumers might be weighing the vegetable's benefits against the risks of contamination.

Spinach is known for its high fiber content and its abundance of antioxidants and vitamins that studies have shown might decrease the risk of stroke and developing cataracts. The leafy green that gave Popeye his fictional super-strength might also promote super-sharp eyesight in the real world.

Green vegetables like spinach, kale and broccoli are particularly rich in two antioxidants called lutein and zeaxanthin that produce a substance which scientists think helps protect the eyes against age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the leading cause of irreversible blindness in Western societies. Researchers at the University of Manchester announced today that they are now using a new device to investigate whether the substance can help people who already suffer from the disease.

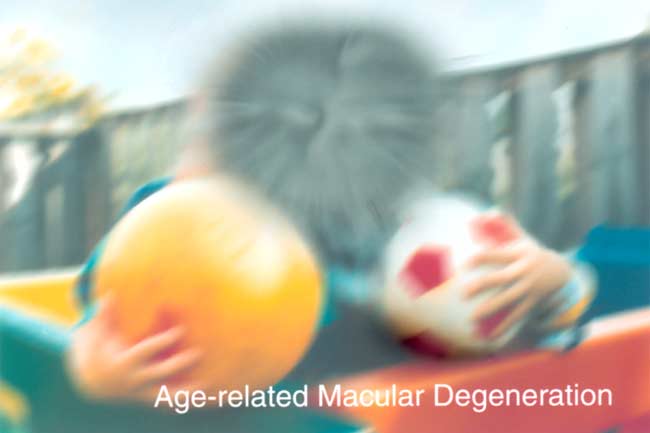

AMD primarily affects elderly people, and sufferers slowly lose their central vision, which makes day-to-day activities difficult. [Example: Good vision / AMD-impaired]

When lutein and zeaxanthin (found in high concentrations in spinach) combine, they form a yellow oil, called a macular pigment. The pigment coats the macula, a small area of the retina that is responsible for distinguishing details and colors in central vision, and is thought to prevent the destruction of retinal cells by excess light and oxidation.

"Our work has already found strong evidence to suggest that macular pigment provides some protection against AMD, but we want to discover whether eating vegetables rich in these chemicals will have a direct impact on the disease," said Ian Murray, the lead researcher of the new study.

The researchers have built a device to measure the levels of macular pigment in people with early stages of the disease. If they are found to have low levels, they can then be advised to eat more spinach and other vegetables rich in the antioxidants.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Having their macular pigment measured and learning about the health of their eyes might be the first step to a change in lifestyle for many people," Murray said.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus