The 10 Weirdest Science Studies of 2019

Oh, the things we do for science!

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Curiouser and curiouser

What do the Loch Ness monster, frozen poop and shape-shifting goo have in common? Scientists delved into the nitty-gritty science behind these oddities and came up with some pretty zany experiments. Other research took a peek into the bizarre lives of vampire trees, snobby mosquitoes and plants that eat amphibians. Sometimes, science is just plain strange — and that's what we love about it! Read on to learn about 10 of the weirdest studies we read this year.

A hunt for Loch Ness monster DNA

According to popular lore, the legendary Loch Ness monster has supposedly lived in a deep Scottish lake for more than 1,000 years. But according to a study conducted this year, Loch Ness seems to be devoid of any signs of "monster DNA." Geneticists drew more than 250 water samples from the vast lake and examined the bits of DNA floating within each. The survey uncovered genetic traces of more than 3,000 species living in and around Loch Ness, including fish, deer, pigs, bacteria and humans. But the team found no evidence of giant reptiles or aquatic dinosaurs, or even massive sturgeons or catfish that could be mistaken for a mysterious lake monster. However, they did uncover an abundance of eels, so it may be possible (though highly improbable) that "Nessie" was actually an overgrown eel.

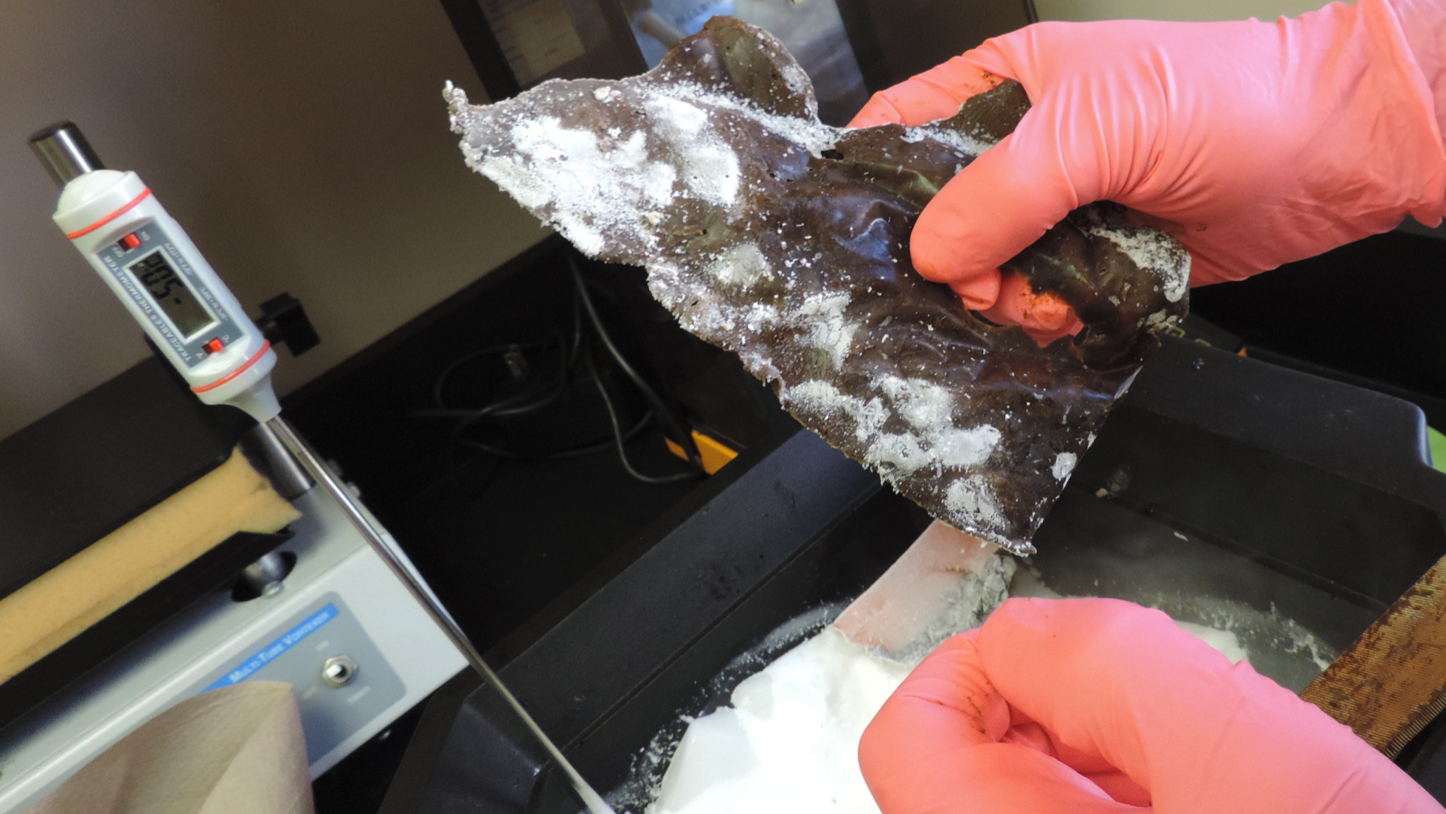

A knife made from … poop?

Many scholars are familiar with the strange story of an Inuit man who, upon being stranded during a storm, fashioned a knife from his own frozen poop and used it to butcher a dog. Although the tale is famous among anthropologists, none have attempted to craft their own blade from frozen fecal matter — until this year, that is, when a team of researchers took a hack at crafting their own poop knives. The lead study author, Metin Eren, adopted an "Arctic diet" for eight days to supply the needed raw materials, which the team then froze and shaped into blades with metal files. But when the team attempted to carve up a pig hide with their new knives, the blades only left brown streaks along the meat. "This idea that a person made a knife out of their own frozen feces — experimentally, it is not supported," Eren told Live Science.

Article continues belowPlants that eat salamanders

The carnivorous northern pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea) traps unwary insects in its goblet-shaped leaves and digests the bugs for their nutrients. But earlier this year, scientists were shocked to find pitcher plants chowing down on salamanders as well. A team of researchers sampled several hundred pitcher plants in Ontario's Algonquin Provincial Park and found that about 20% of the plants contained at least one juvenile salamander, while many plants captured several of the amphibians at once. The salamanders drowned, starved or were cooked to death in the acidic pitcher fluid and, once dead, decomposed in about 10 days. The ravenous plants may gobble up as much as 5% of the bog's juvenile salamander population each year, the team estimated.

Your tongue can smell like a nose can

No, this doesn't mean you should stop and lick the flowers — but our senses of taste and smell may be even more entangled than we once thought. In a study published in April, scientists exposed lab-grown human taste cells to odor molecules and found that the cells reacted to scents in the same way that the smell-sensing cells in our nasal passages do. When an odor molecule touched down on one of the taste cells, the chemical plugged into a receptor on the cell's surface. In the body, the interaction between the odor and receptor would normally trigger a chain reaction inside the cell, causing it to shoot off a message to the brain.

Vampire tree leaches nutrients from its neighbors

Deep in a New Zealand forest, an unassuming tree stump clings to the roots of nearby conifers, sucking up their hard-earned water and nutrients. Scientists stumbled upon this botanical vampire while hiking in West Auckland, New Zealand, as they were surrounded by hundreds of kauri trees — a species of conifer that can grow up to 165 feet (50 meters) tall. During the day, the towering trees shuttled water from their roots into their leaves. By night, the squat stump pumped leftover water and nutrients from its neighbors' roots into its own. "Possibly we are not really dealing with trees as individuals, but with the forest as a superorganism," study co-author Sebastian Leuzinger, an associate professor at the Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand, said in a statement.

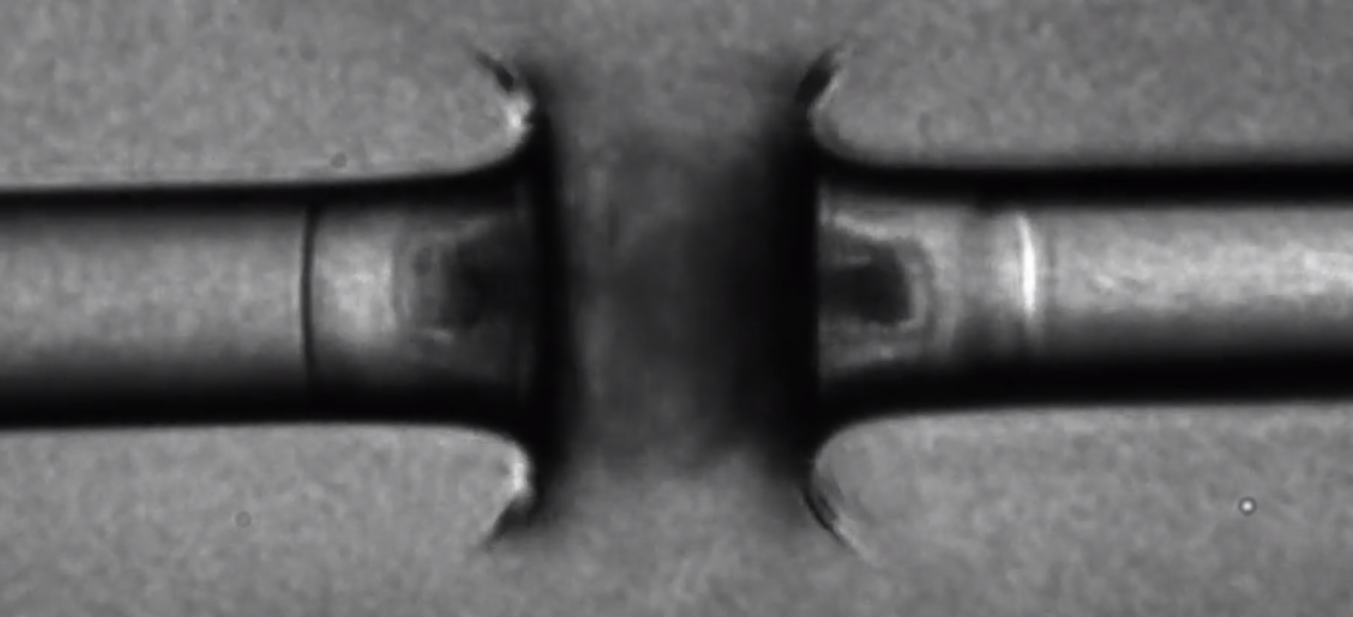

A sound so loud it vaporizes water

If scientists shoot tiny X-ray lasers at a stream of water, does it make a sound? Oh, yes it does. This year, researchers created what may be the loudest possible underwater sound, using just this setup. Contained within a vacuum chamber, pulsing beams from an X-ray laser collided with a razor-thin water jet, instantly splitting the jet in two and vaporizing the fluid on each side. Pressure waves rippled out from the point of contact and released a 270-decibel sound that would make NASA's loudest-ever rocket launch sound hushed by comparison. If the sound were any louder, it might have boiled the very liquid it was traveling through.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Can black holes evaporate?

Famed theoretical physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking once predicted that black holes not only suck celestial objects into their depths but also emit particles into space. He theorized that these particles slowly strip black holes of their mass and energy, until eventually, the black hole disappears — but physicists never thought they could prove it.

This year, however, a team of researchers finally spotted this elusive Hawking radiation in laboratory experiments. The team created a "waterfall" from a stream of extremely cold gas to model the event horizon of a black hole, the invisible boundary beyond which nothing can escape. Quantum sound waves fed into the gas could flow away from the waterfall if inserted into the "stream" nearby, but sound waves in the waterfall itself became trapped by the relentless current. The escaped sound waves can be seen as analogous to particles of light escaping the pull of a black hole, suggesting that Hawking's theory was right.

Mosquitoes don't like Skrillex

In case anyone was wondering, research suggests that female mosquitoes don't care for the musical stylings of Skrillex. A study published in March found that the pests suck less blood and have less sex after listening to the song "Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites" in 10-minute spurts, at least compared with mosquitoes left in silence. But why did a team of insect researchers subject the bugs to Skrillex in the first place? Well, they wondered whether loud music could be used to manipulate mosquito behavior as an "environmentally friendly" alternative to insecticides. The loud music may have distracted the mosquitoes, preventing them from homing in on a nearby food source and potential mates, the team suggested.

A particle that isn't a particle

This year, physicists may have finally spotted an odderon — a particle that really isn't. Particles such as electrons and protons stick around for extended periods, while odderons, a kind of "quasiparticle," blink in and out of existence. Scientists first predicted the existence of odderons in the 1970s, thinking that the particles might materialize when an odd number of teeny particles called quarks get released during the violent collision of protons and antiprotons. Researchers resurrected the decades-old idea when they sent particles crashing into each other at the world’s largest atom smasher, the Large Hadron Collider. The team spotted some strange differences in the way protons collide with other protons as compared to antiprotons, and the existence of odderons may explain why that discrepancy exists.

Oobleck unmasked

Oobleck is a delightful goop that runs like a liquid but snaps into a solid state when you smack it. You can mix up your own oobleck by stirring up a slurry of cornstarch and water, and with the help of a new computer model, you can predict how the bizarre substance will react to various forces. Scientists used the model to simulate how oobleck would behave if it were pressed between two plates, were hit by an airborne projectile or were run over by a virtual wheel. They hope to find innovative uses for the goo, like temporarily filling dangerous potholes on major roads.

- 14 Most Bizarre Scientific Discoveries of 2018

- 10 Times Earth Revealed Its Weirdness in 2017

- Weird and Funny Science Gifts That Are Sure to Make You Laugh

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus