Global 'time signals' subtly shifted as the total solar eclipse reshaped Earth's upper atmosphere, new data shows

During the historic April 8 total solar eclipse, a government radio station in Colorado started sending out slightly shifted "time signals" to millions of people across the globe as the moon's shadow altered the upper layers of our atmosphere. However, these altered signals did not actually change the time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

As millions of people looked up to the sky to see the moon temporarily (and completely) block out the sun during the April 8 total solar eclipse, the extraordinary cosmic event also shifted invisible "time signals" being beamed from the U.S. across the globe, new data shows. But don't worry, these altered signals did not result in any changes to the time we observed during or after the event.

The shifted time signals came from the WWV radio station — a National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) facility located in Fort Collins, Colorado, that monitors and broadcasts high-frequency radio waves.

WWV, which is jointly operated by NASA's Ham Radio Citizen Science Investigation (HamSCI), constantly broadcasts a special signal embedded with "digital time codes" to millions of receivers around the world. Devices that pick up this signal interpret the digital codes embedded within the transmission and use them to stay in sync with NIST's atomic clocks, which serve as the gold standard for all U.S. timekeeping.

Article continues belowRelated: 6 strange things observed during the April 8 solar eclipse: From doomed comets to 'diamond rings'

However, in order to do this, the signal must be bounced off the ionosphere — the upper part of the atmosphere between 50 and 370 miles (80 and 600 kilometers) above the Earth's surface, where gases are turned into plasma, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And during the eclipse, the ionosphere was slightly altered as the moon's shadow raced across the U.S. at more than 1,500 mph (2,400 km/h).

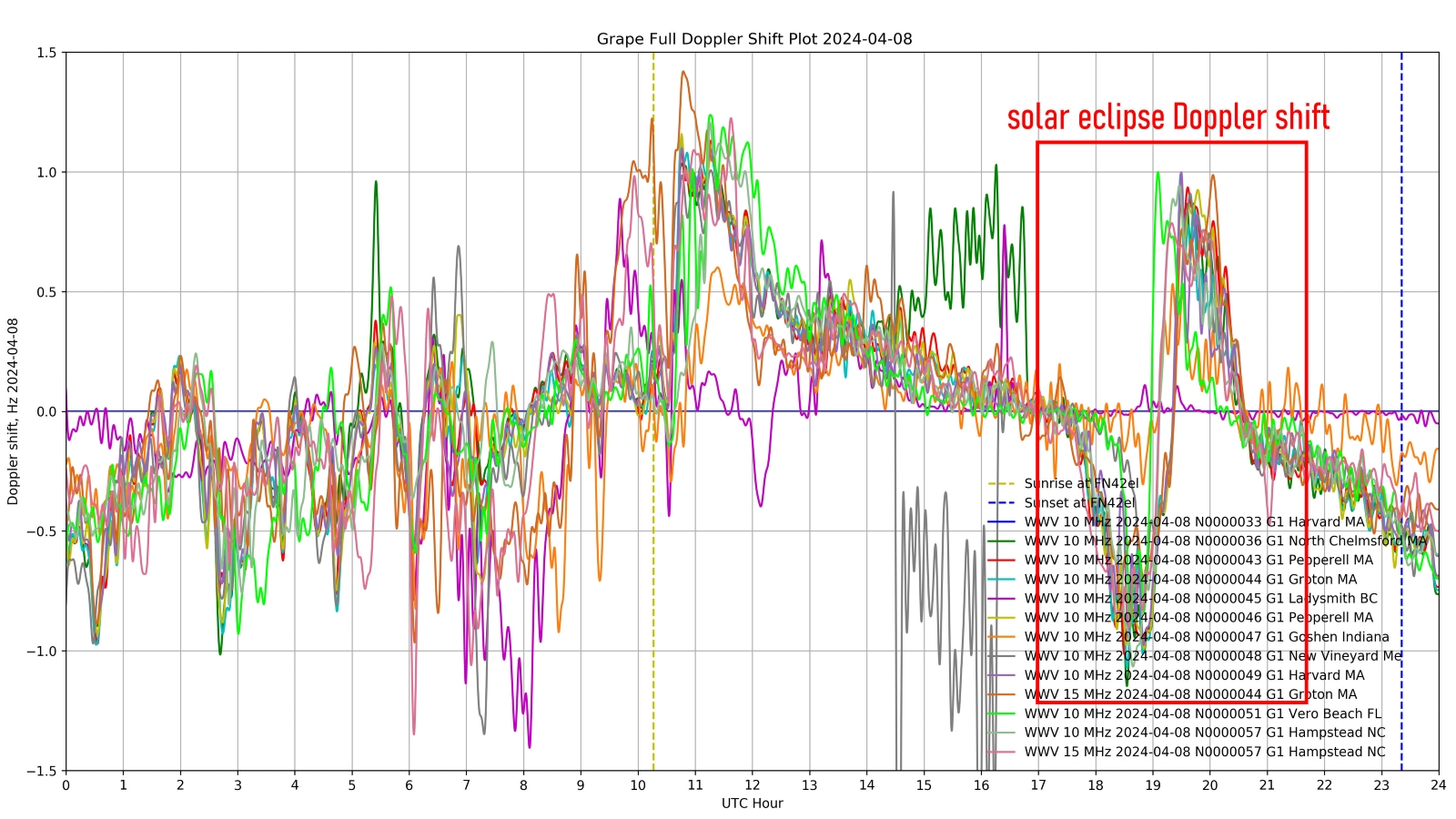

As a result, the frequency of the signal being bounced off this part of the atmosphere was shifted slightly, Spaceweather.com initially reported. Similar frequency shifts were also seen in other radio signals sent or received by amateur radio operators across the country, HamSci reported.

Luckily, the change to the WWV signal's frequency was so small that the digital time codes transmitted by the radio waves were unaltered, meaning devices that rely on the signal to keep time were unaffected, according to Spaceweather.com.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Radio waves from other major time signal stations across the world, including WWV's sister station WWVH in Hawaii, were unaffected by the eclipse.

A 'quick flip to darkness'

The shift to the WWV signal is known as a Doppler shift, which happens when the distance a signal must travel either increases or decreases. These changes can either stretch or truncate the waves, which in turn alters the frequency and wavelength of the waves.

Similar Doppler shifts happen naturally at least twice every 24 hours as the sun rises and sets, Kristina Collins (radio callsign KD8OXT), a researcher at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado, told Live Science in an email. "Every day, light from the sun causes photoionization in the ionosphere, causing ionospheric layers to move, combine or separate."

From sunrise onward, this causes the ionosphere to expand, which means radio waves do not travel as far before bouncing off this invisible barrier, Collins said. But when the sun sets, the ionosphere contracts, allowing signals to travel farther before being bounced back to the surface, she added. As a result, radio signals have to travel farther at night, which slightly increases their wavelengths.

The same thing happened during the "quick flip to darkness" of the eclipse, Collins said. "Essentially, it's like a day/night cycle in miniature."

Similar, less extreme Doppler shifts can also be caused by changes in solar activity, including large gusts of solar wind, explosive solar flares and coronal mass ejections, which can all alter Earth's ionosphere when they bombard our planet, Collins added.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus