Mysterious 'magic' islands that come and go on Saturn's moon Titan finally have an explanation

Bright spots that appear and vanish on Saturn's moon Titan have a seemingly simple explanation — they're floating chunks of frozen organic material.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

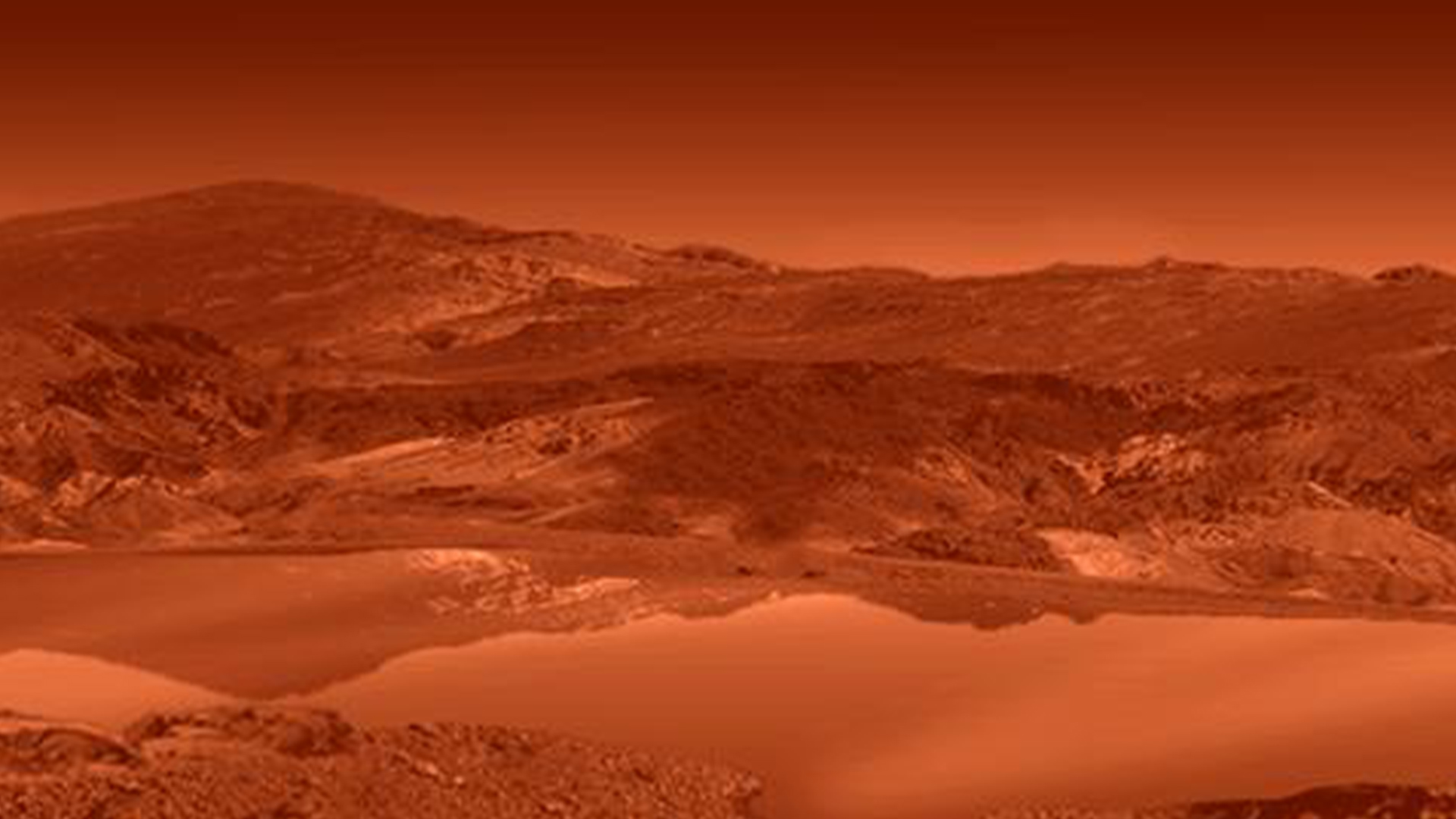

Saturn's moon Titan may be known for its methane lakes, but it also has "magic" islands — mysterious bright spots atop the lakes that come and go, with no known explanation. However, a new study, published Jan. 4 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, proposes a surprisingly simple explanation for the magic islands: They're floating chunks of frozen organic material.

"I wanted to investigate whether the magic islands could actually be organics floating on the surface, like pumice that can float on water here on Earth before finally sinking," study lead author Xinting Yu, a planetary scientist at the University of Texas at San Antonio, said in a statement.

Titan is a particularly strange place in the solar system, with a "methane cycle" somewhat analogous to the water cycle on Earth. Instead of liquid water oceans, it has placid liquid methane lakes, whose waves measure only a few millimeters. Instead of having an oxygen atmosphere, Titan is filled with hazy clouds of organic molecules.

Yu wondered what would happen if clumps of that atmospheric haze fell into the lakes. Would they float or sink — or perhaps even float for a while before eventually succumbing to the liquid, just like the magic islands?

"For us to see the magic islands, they can't just float for a second and then sink," Yu said. "They have to float for some time, but not for forever, either."

The researchers used physics and chemistry calculations to determine what happens to particles when they hit the lake, and, if they didn’t sink, how long they’d stay afloat. They found that the clumps of solids wouldn't dissolve in the lakes. But they would also be too heavy to float — that is, unless they were extremely porous, full of holes just like the pumice stones Yu imagined.

The researchers found that if the clumps were big enough and had enough holes, they would float until the methane slowly seeped in and dragged them down. These conditions replicated the behavior of the magic islands. To reach the critical mass needed to stay afloat, clumps might first form on the shoreline, with pieces breaking off and drifting to "sea" like glaciers on Earth, the team suggested.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It seems like the islands aren't so magical after all — just an unfamiliar version of the same planetary phenomena we know on our home world.

Briley Lewis (she/her) is a freelance science writer and Ph.D. Candidate/NSF Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles studying Astronomy & Astrophysics. Follow her on Twitter @briles_34 or visit her website www.briley-lewis.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus