Earth's highest, coldest, rarest clouds are back. How to see the eerie 'noctilucent clouds' this summer.

Look North as the stars appear in June and July to have a chance of seeing rare noctilucent (or 'night-shining') clouds with the naked eye.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Look up an hour or two after sunset and before sunrise over the next few months and you may see ethereal blue, silver or golden streaks in the Northern Hemisphere's northern skies.

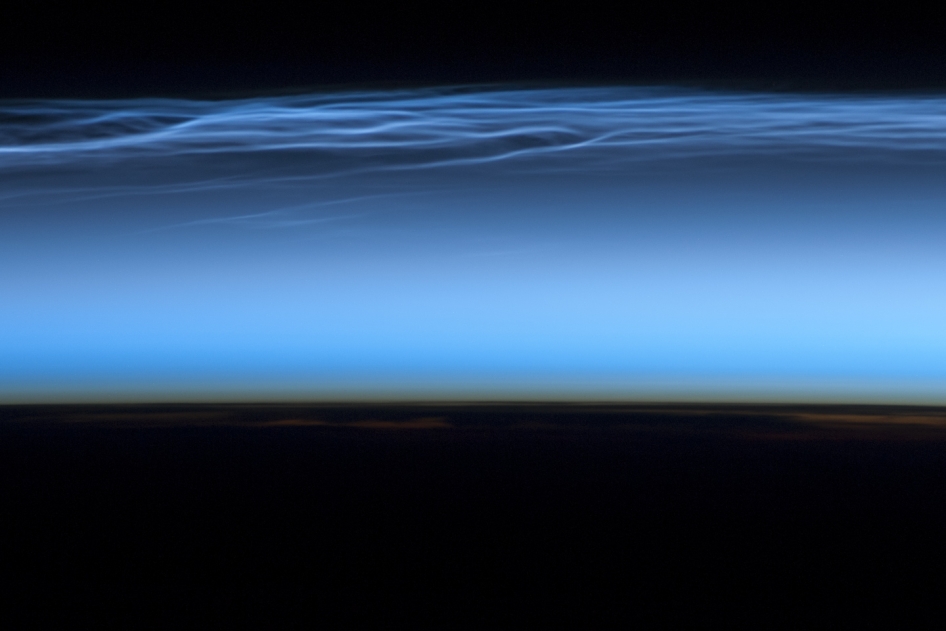

Called noctilucent clouds (meaning "night-shining" clouds in Latin) or NLCs, these strange-looking patterns in the sky are the highest, driest, coldest and rarest clouds on Earth, according to a 2018 study of the phenomenon.

These shimmering, night-shining clouds appear in the mesosphere — a layer of Earth's atmosphere above the stratosphere and below the thermosphere, about 47 to 53 miles (76 to 85 kilometers) above Earth's surface. Sometimes dubbed "space clouds," NLCs form just below the invisible boundary where Earth's atmosphere ends and outer space begins, roughly 62 miles (100 km) above the planet's surface, according to NASA.

Related: How much does a cloud weigh?

NLCs occur when water vapor freezes into ice crystals that cling to dust and particles left by falling meteors high in the atmosphere, which reflect sunlight. The peak season for observing NLCs from the Northern Hemisphere is around the summer solstice in late June through the end of July, when they're most easily visible from about 50 to 70 degrees north latitude, according to Windy. However, some NLCs have already been spotted this month in colder, northern regions like Denmark, according to Spaceweather.com.

NLC sightings were at a 15-year high last summer, according to the Washington Post. Sightings have become more frequent in recent years and at lower latitudes, possibly because climate change generates more water vapor in the atmosphere as a result of increased atmospheric methane, according to NOAA.

For the best chance to see some NLCs in the evening, you'll need a good view low to the northern horizon as the stars begin to shine in late twilight. It's typical to see displays in the bottom 20 to 25 degrees of the northern sky, according to Sky & Telescope. Naked eye viewing is the best way to find noctilucent clouds, but with a pair of the best binoculars for stargazing, you'll get a fabulous close-up of the structure of one of the summer's most elusive and impressive sky sights.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jamie Carter is a Cardiff, U.K.-based freelance science journalist and a regular contributor to Live Science. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and co-author of The Eclipse Effect, and leads international stargazing and eclipse-chasing tours. His work appears regularly in Space.com, Forbes, New Scientist, BBC Sky at Night, Sky & Telescope, and other major science and astronomy publications. He is also the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus