Stars that brush past black holes live longer, stranger lives after their close encounters with death

A new study shows survivor stars can live billions of years longer than normal, carrying chemical fingerprints of their violent encounters with the Milky Way's black hole.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

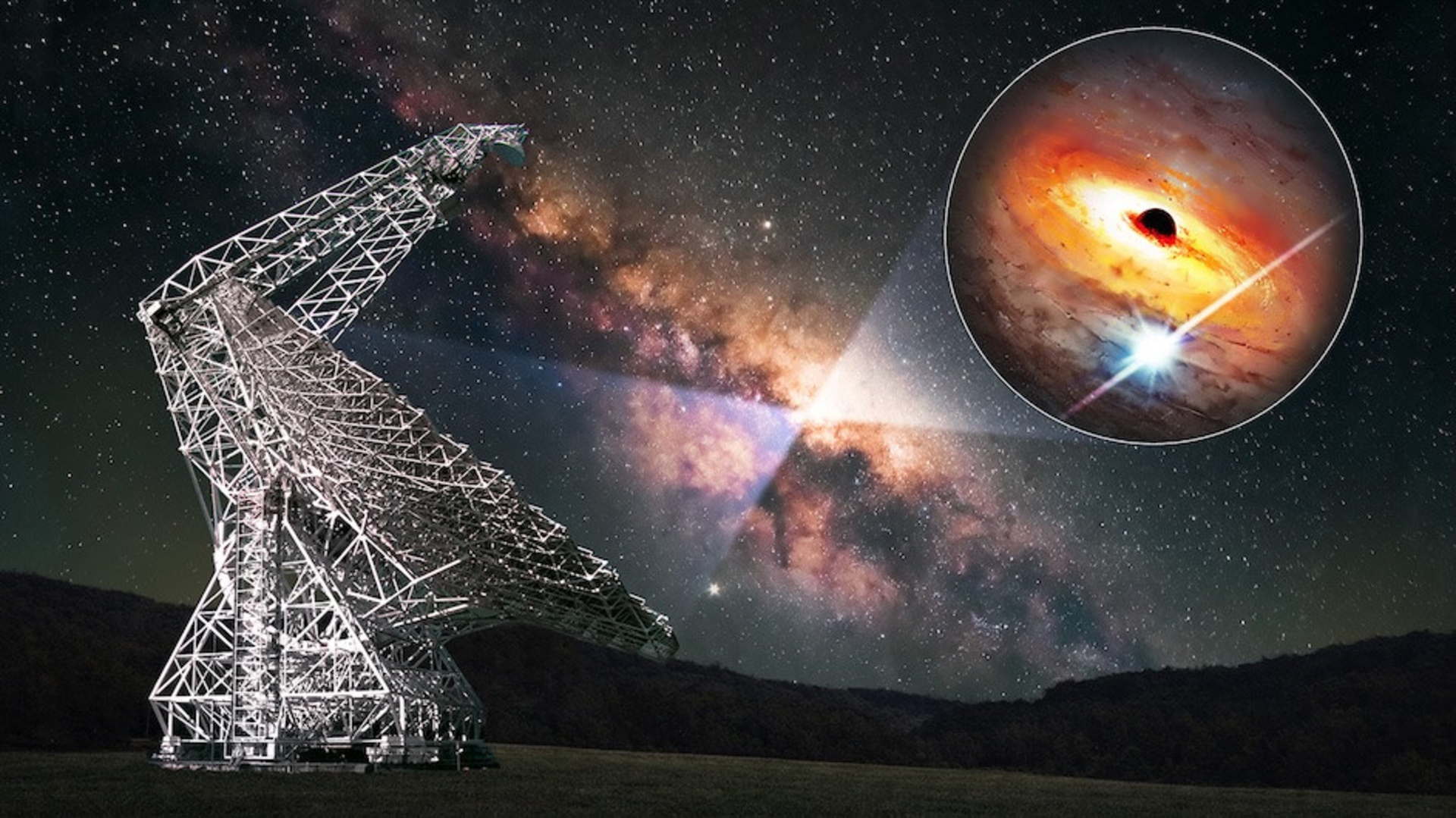

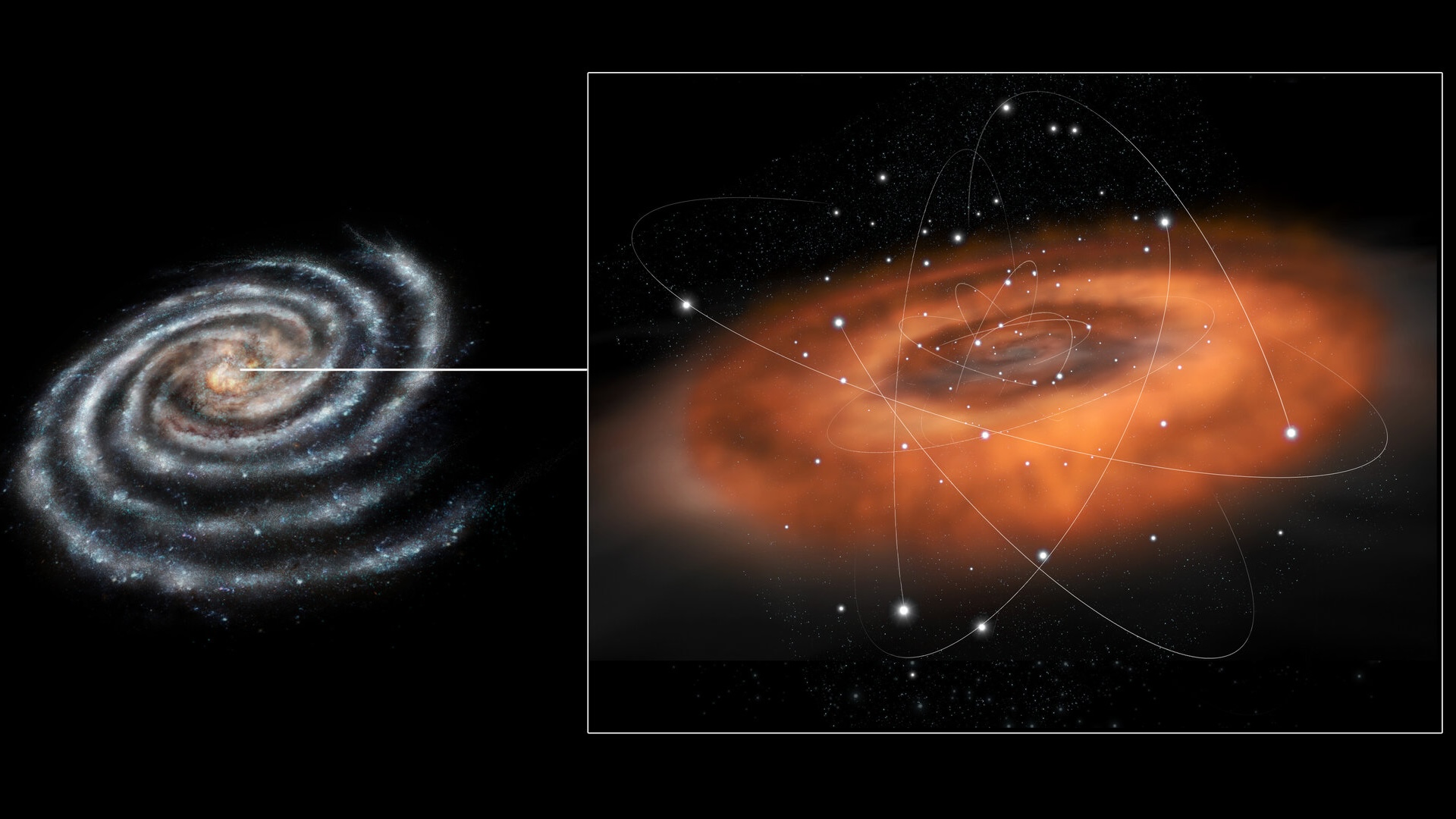

Black holes are often seen as cosmic monsters that swallow anything unlucky enough to stray too close. But new research suggests they do not always win — some stars can skim the Milky Way's central black hole, Sagittarius A*; lose mass; and stagger away. Scarred but alive, these survivors shine brighter than before, leaving clues that astronomers are only now learning to read.

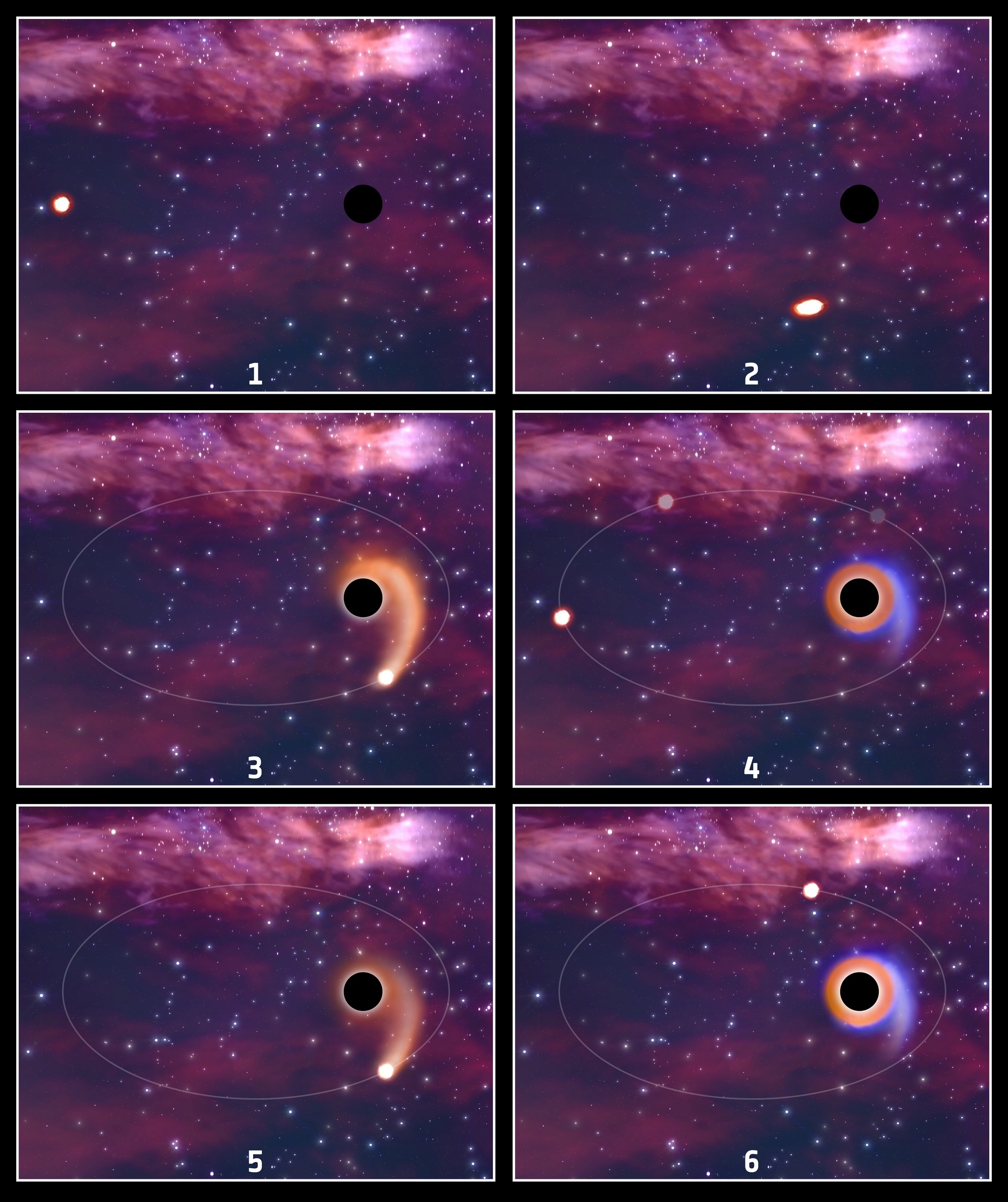

"Just as the moon pulls tides on Earth, a black hole tugs on a star with far greater force," Rewa Clark Bush, a doctoral candidate in astronomy at Yale University and lead author of the study, told Live Science in an email. Push too far, and the star unravels. Yet some withstand the strain. "One of the stars we modeled lost over 60 percent of its envelope but still retained enough core material that it survived and escaped," Bush said.

The authors think that by counting survivor stars, astronomers might measure how often Sagittarius A* feeds on nearby stars — and the number may help to explain how our galaxy's central black hole grew to 4 million times the mass of the sun.

"Black holes are like chickens in a coop that only eat what they are fed," Heino Falcke, a professor of astrophysics at Radboud University in the Netherlands, not involved in the study, told LiveScience in an email. "The study provides a new toolbox to find these marred stars and learn about the history of our galactic center black hole's feeding habits."

Brighter after the storm

The team used advanced 3D simulations to follow stars brushing past the Milky Way’s black hole and track their long-term evolution. The results, published Aug. 27 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, showed that a near miss — known as a partial tidal disruption — can trigger a brilliant transformation. A survivor star may throw off ribbons of plasma, swell to many times its original size, and glow up to 10 times brighter for thousands of years.

The show, however, does not last. Surviving stars gradually shrink and begin to masquerade as ordinary stars. Their only giveaway is chemical: The violence dredges up helium and nitrogen from the core to the surface.

"You would need to take spectroscopic data," Bush said — breaking starlight into its component colors — "to notice anomalies that reveal the trauma."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Giuseppe Lodato, an associate professor of astrophysics at the University of Milan, not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that although survivor stars are well known to astrophysicists, this study stands out for characterizing their brightness and chemical evolution over time.

A clue to the G objects

The study may also address a mystery that has lingered in the Milky Way's core for years. Astronomers have observed several fuzzy light sources known as G objects. These bodies move like stars yet look like diffuse clouds in infrared images. Survivor stars fit the description — they're swollen and wrapped in material blown off during disruption.

"It is very exciting how the authors make a link with the still mysterious and heavily debated G objects," Selma de Mink, scientific director at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Germany, not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

Spotting these stars is not an easy task. Sjoert van Velzen, an assistant professor at the Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that even the most ambitious new surveys, such as those undertaken by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, will reveal thousands of bright flares from complete tidal disruptions in distant galaxies, not the faint remnants that slip away.

"The galactic center is crowded, with stardust blocking most optical light," de Mink said. Infrared instruments such as GRAVITY, which she likened to thermal cameras piercing smoke, are better suited to identifying swollen stars that may hide among the puzzling G objects.

Anirban Mukhopadhyay is an independent science journalist. He holds a PhD in genetics and a master’s in computational biology and drug design. He regularly writes for The Hindu and has contributed to The Wire Science, where he conveys complex biomedical research to the public in accessible language. Beyond science writing, he enjoys creating and reading fiction that blends myth, memory, and melancholy into surreal tales exploring grief, identity, and the quiet magic of self-discovery. In his free time, he loves long walks with his dog and motorcycling across The Himalayas.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus