Rare Byzantine swords found in medieval stronghold

Experts are calling them hybrid Byzantine ring pommeled swords.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Archaeologists in Turkey have discovered two "rare and unique" swords in a heavily fortified city from the Byzantine Empire, a new study finds. One of the swords, unearthed in a church, may have been placed there as an offering.

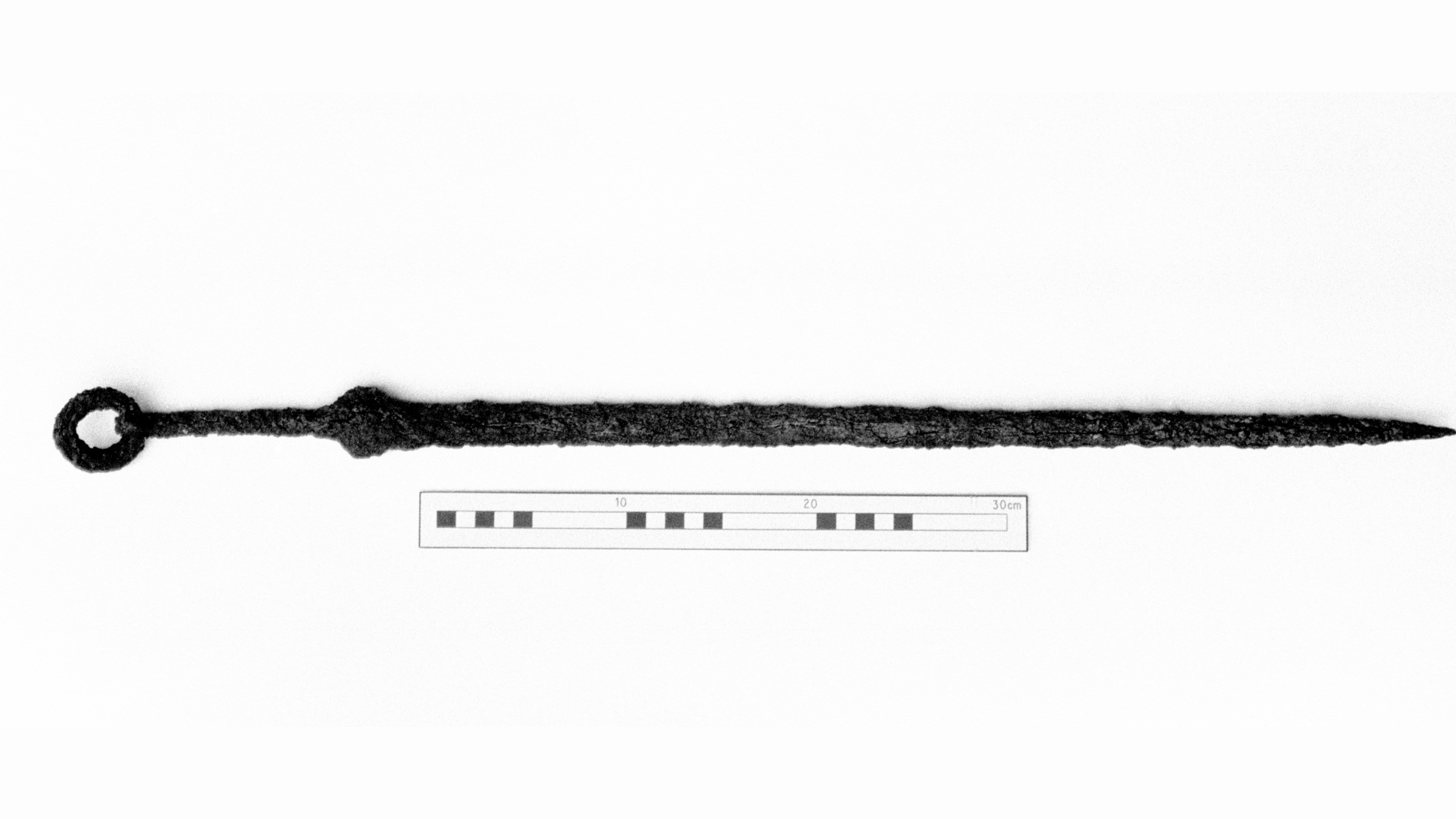

Both iron weapons are ring pommeled swords, meaning that the pommel — a rounded knob at the end of the handle — is shaped like a ring. Ring pommeled swords were a rarity in the Byzantine, but these blades are also unique for another reason: Intriguing features on the swords distinguish "them from the ring pommeled swords of the nearby civilizations," the researchers wrote in the study.

The swords are so unique, it's difficult to determine what ethnicity or mercenary group wielded them about 1,000 years ago, the researchers said.

Related: In photos: The last century of Samurai swordsmen

Archaeologists discovered the swords in Amorium, a Byzantine city that was an important crossroad between Constantinople, the empire's capital, and other major cities, such as Nicaea and Ancyra (modern-day Ankara). Amorium was also, temporarily, a military hotspot and became a stronghold that served as the region's first defense line against the Arab invasions, including the Arab conquest of Amorium in A.D. 838, the researchers said.

Researchers have done systematic excavations in Amorium since 1988, leading them to find the two ring pommeled swords: They unearthed the first, a fragmentary and corroded sword, in the atrium of a church in 1993, while they found the second sword in 2001 in the lower part of the city. Both swords date to the 10th and 11th centuries, during the middle Byzantine period (A.D. 843 to 1204).

The discovery of a sword in a church may be "considered bizarre," as it was custom at that time to lay down weapons in holy places, said study lead researcher Errikos Maniotis, an independent researcher who has a master's degree in Byzantine archaeology from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in Greece.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's possible that the sword wasn't brought into the church with the intention of violence, however, but as a votive offering — a special object purposefully left for god(s), religious leaders or establishments. "It is known from the [historic] sources that weapons have been deposited as votive offerings in churches," Maniotis told Live Science in an email.

For instance, Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos, the Byzantine emperor from A.D. 913 to 959, wrote that St. Theodore Teron's shield was hung as a relic under the dome of a Byzantine church honoring him, Maniotis said. Weapons placed in churches are "usually associated with holy relics connected with the warrior saints," he noted. "Moreover, we have the deposit of armament in Mount Athos monasteries [in Greece], such as a chainmail shirt that is stored in Iveron Monastery. So, this sword could have a votive character, offered by its owner to the church along with other objects, perhaps."

The second sword, found in the lower city, has a 5.5-inch-long (14 centimeters) handle and a double-edged blade that was at least 24 inches (61 centimeters) long, Maniotis and study co-researcher Zeliha Demirel-Gökalp wrote in the study. Demirel-Gökalp is the director of the excavations at Amorium and a professor in the Department of Art History, with an expertise in Byzantine art, at Anadolu University in Turkey.

Related: The coolest ancient weapons discovered in 2020

The dimensions of this sword suggest that a soldier in the Byzantine army may have used it as a secondary, optional sword during battle, the researchers said.

Though rare in the Byzantine Empire, ring pommeled swords are known from other cultures. The earliest known ring-shaped pommel can be traced back to the Chinese Han Dynasty (206 BC. to A.D. 220), and the practice spread to the nomadic Scythians and Huns, the researchers said. Ring pommeled swords are also seen in other cultures, including the Sarmatians, who lived in Central Asia, and the Romans, who may have adopted the practice from Sarmatian mercenaries.

However, unlike previously discovered swords, the sword found in the church has a structure that looks like a cross-guard — a piece of metal that sits perpendicular to the blade at the end of the handle. Cross-guards are often used to identify old swords, and this one resembles a "sleeved cross-guard," the researchers said. This feature, as well as others, have never been seen on ring pommeled swords before, "which is a fact that makes this specimen unique," the researchers wrote in the study.

The swords are so unusual, the researchers proposed giving their design a new name: hybrid Byzantine ring pommeled swords. Given that they were found near each other in Amorium, perhaps "there was a specific armory in the city that manufactured this certain type of ring pommeled swords," the researchers said in the study. "Or, it is just maybe a coincidence."

The Amorium excavations are supported by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Turkey, the Turkish Historical Society and Anadolu University. The study was published in December 2021 in the Journal of Art History.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus