Bizarre, primeval sharklike fish is unlike any vertebrate ever discovered

It is one of several new finds that could rewrite how scientists understand fish evolution.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

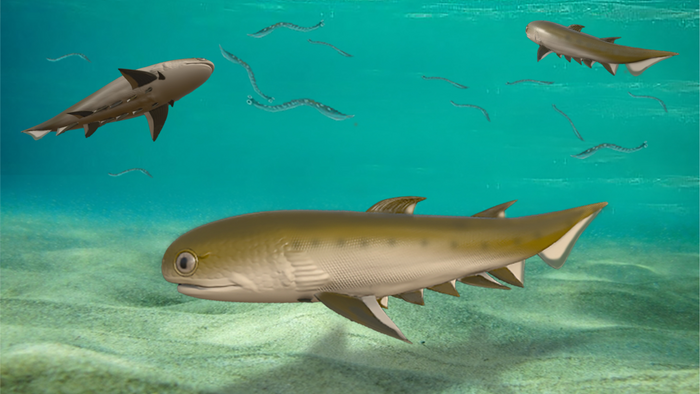

Researchers in China have uncovered the remains of a 439 million-year-old shark-like fish with unusual features that "set it apart from any known vertebrate," or animal with a backbone. The bizarre creature, which is covered in spines and "bony armor," is the oldest undisputed jawed vertebrate ever discovered, a new study reports.

Scientists discovered the remains of the newly identified, extinct species at the Rongxi Formation, a renowned fossil site in Guizhou province, in southern China. The researchers named the species Fanjingshania renovata, after a nearby mountain known as Fanjingshan.

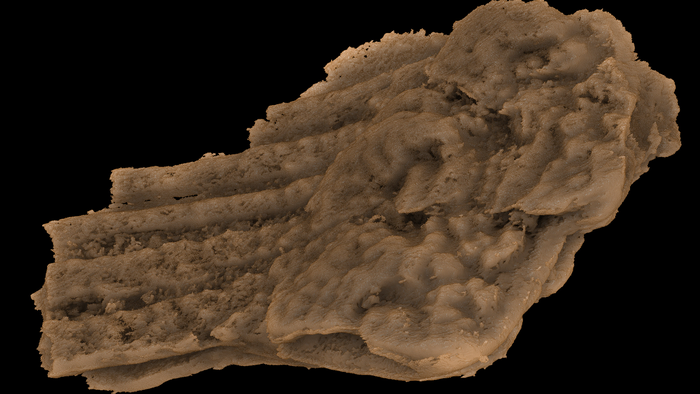

The team collected thousands of fossilized skeletal fragments, scales and teeth from the site and then painstakingly recreated what the ancient fish might have looked like. Their findings were published online Sept. 28 in the journal Nature.

F. renovata belongs to an extinct group of shark-like creatures known as acanthodians, also called "spiny sharks," which have spiny fins and bony plates surrounding their shoulder areas. On the fish family tree, acanthodians lie somewhere between chondrichthyans, which include modern sharks and rays, and osteichthyans, or bony fish. Acanthodians have shark-like body plans, but their bony skin plates and skeletons are similar to those of bony fish. Researchers suspect that F. renovata may be a close relative of the undiscovered common ancestor of the two groups.

Related: Great white-shark-sized ancient fish discovered by accident from fossilized lung

The newfound species dates back to the Silurian period, between 443.8 million and 419.2 million years ago, and is around 15 million years older than the oldest known jawed fish, making it the oldest jawed vertebrate to date, researchers said in a statement.

Scientists are especially interested in the emergence of jawed fish because their evolution was a major point in the diversification of vertebrates. The discovery will help researchers "gain much-needed information about the evolutionary steps leading to the origin of important vertebrate adaptations, such as jaws, sensory systems, and paired appendages," study co-author Min Zhu, a paleontologist with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said in the statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A unique specimen

Although F. renovata does share multiple characteristics with other acanthodians, the researchers said it also had features that set it apart from others in the group.

One of the main differences is in the fish's shoulder armor, which covers a greater area than the armor of other acanthodians and is fused to multiple spines, the researchers wrote.

The creature's spiny fins were also covered in unusual teeth-like scales that the team suspects would fall out in clumps and regrow. Similar scales are seen in modern sharks, but they do not get replaced in this way, according to the statement.

The fossilized bones of F. renovata also show evidence of a process known as resorption,when parts of bones or teeth break down and are later replaced, often during the organism's development.

"This level of hard tissue modification is unprecedented in chondrichthyans," lead study author Plamen Andreev, a paleontologist at Qujing Normal University in China, said in the statement. It shows a "greater than currently understood plasticity" of how early mineralized skeletons developed and points to the evolutionary origins of modern skeletons, including those in humans, he added.

Redefining fish evolution

F. renovata is just one of several fossils that the researchers uncovered at the Rongxi Formation site.

In a separate study, also published Sept. 28 in the journal Nature, the researchers revealed another new species of extinct jawed fish, Qianodus duplicis. This species also dates to around 439 million years ago; however, it was described only from fossilized teeth and scales, which means researchers are more uncertain about exactly which group it may have belonged to.

The same team also described three more extinct fish species from fossils unearthed at the site, reporting them in additional papers published on the same day. Xiushanosteus mirabilis was an armored fish in a group known as placoderms; Shenacanthus vermiforis might have been a placoderm but also has similarities with some jawless fish; and Tujiaaspis vividus belongs to a jawless group of fish called galeaspids, which are known for having helmet-like shields on their heads, according to the Chinese Academy of Sciences. None of these specimens was quite as old as F. renovata or Q. duplicis, but X. mirabilis and S. vermiforis are still older than any other known species of early jawed fish.

Together, these newly described species completely change what scientists know about the evolution of jawed fishes. Past discoveries had suggested that the emergence and diversification of jawed fishes didn't really start until around 420 million years ago, according to the study. But the new fossils show that a variety of jawed fish were already swimming Earth's seas around 20 million years before that.

Related: Sharks are older than the dinosaurs. What's the secret to their success?

"Until this point, we've picked up hints from fossil scales that the evolution of jawed fish occurred much earlier in the fossil record, but have not uncovered anything definite," study co-author Ivan Sansom, a vertebrate paleobiologist at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., said in a statement. "These are the first creatures that we would recognize today as fish-like."

What's more, the researchers suspect that jawed fish actually originated even earlier.

Based on the similarities between F. renovata and modern sharks, rays and bony fish, the team estimated that a hypothetical common ancestor — also a jawed fish — of chondrichthyans and osteichthyans could date back to around 455 million years ago.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus