This 'ancient' monster fish may live for 100 years

These fish may be part of the centenarian club.

Coelacanths, a group of human-size fish once thought to be extinct, may live as long as 100 years — five times longer than previous estimates suggested, a new study finds.

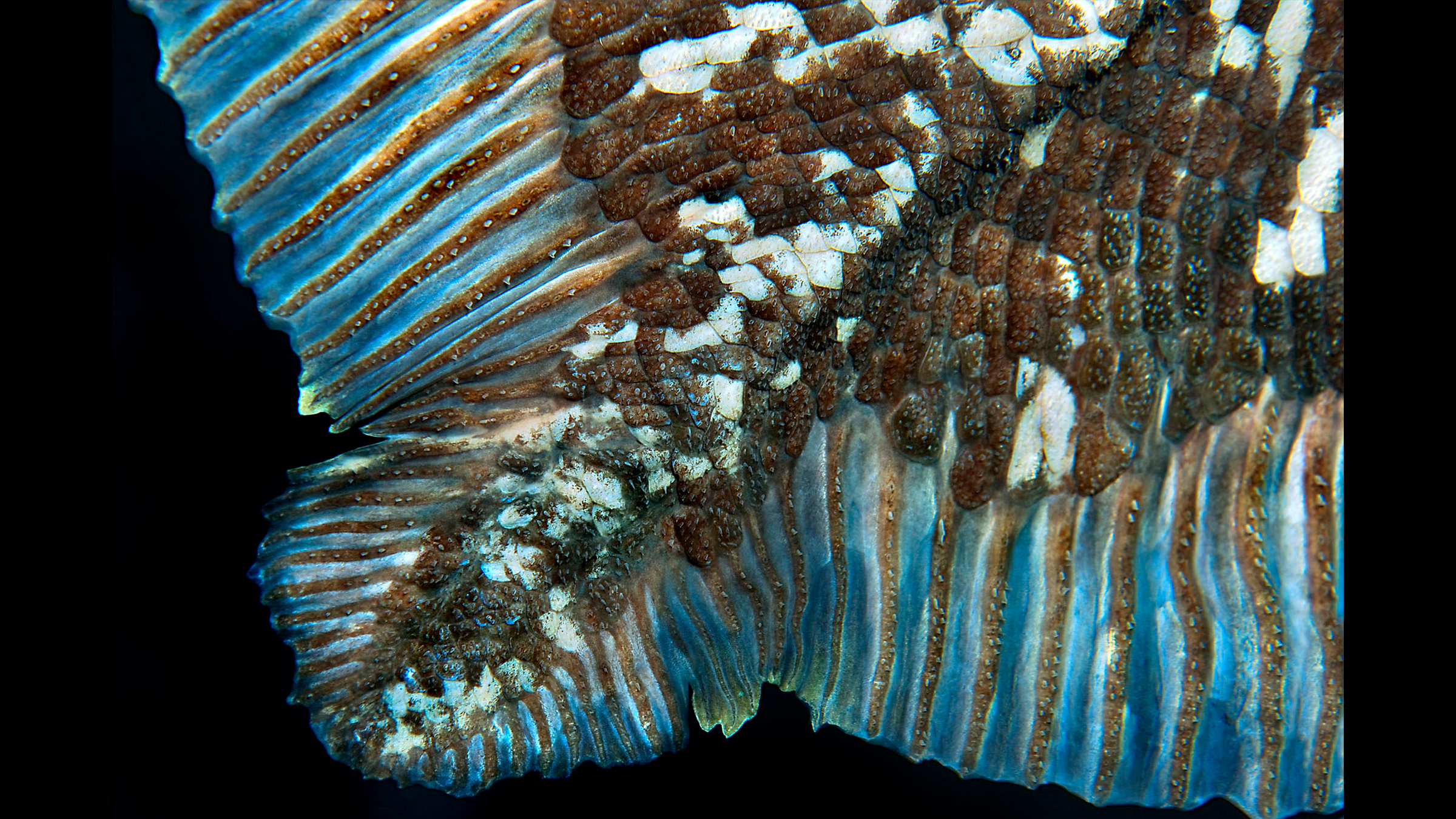

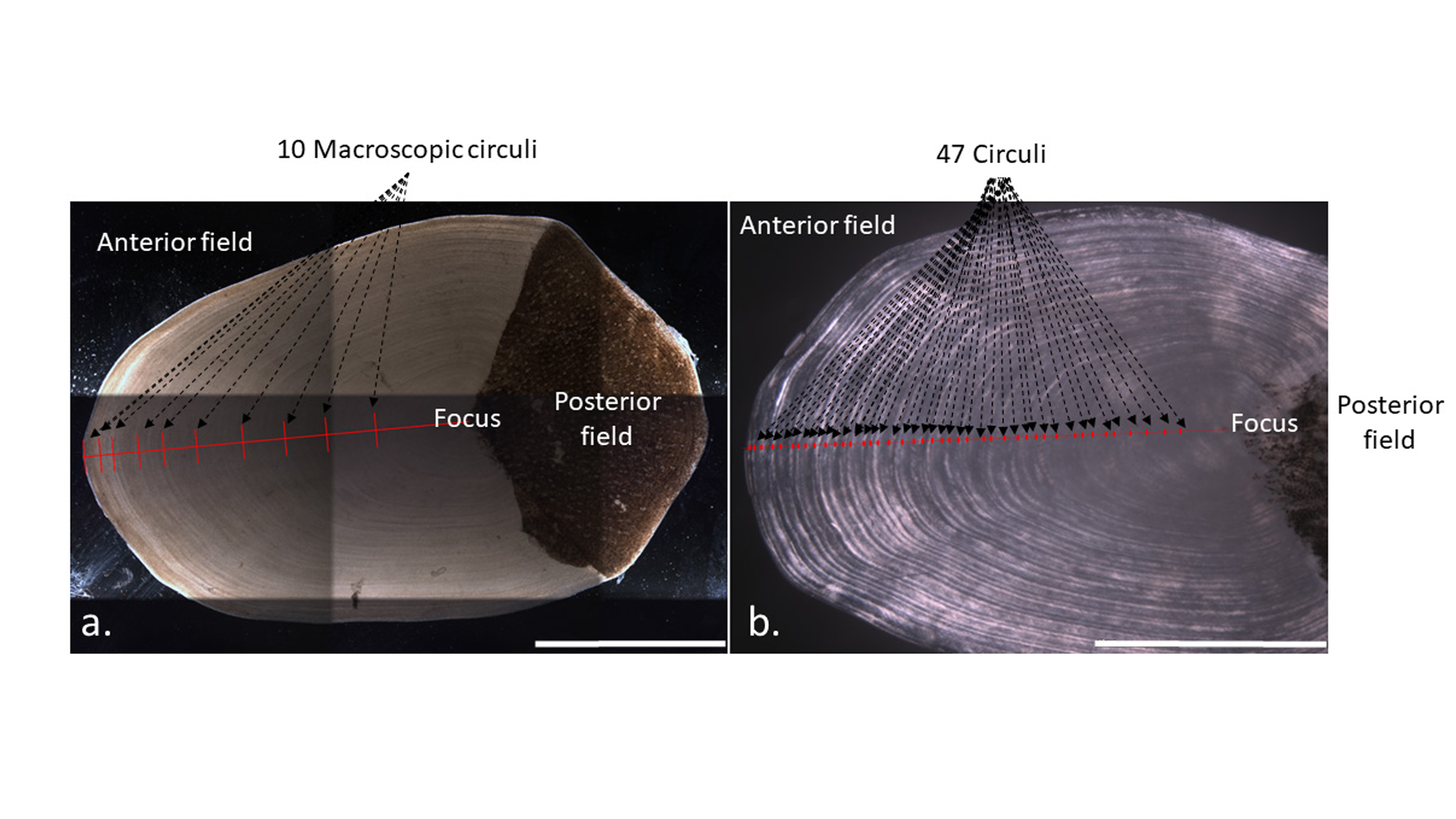

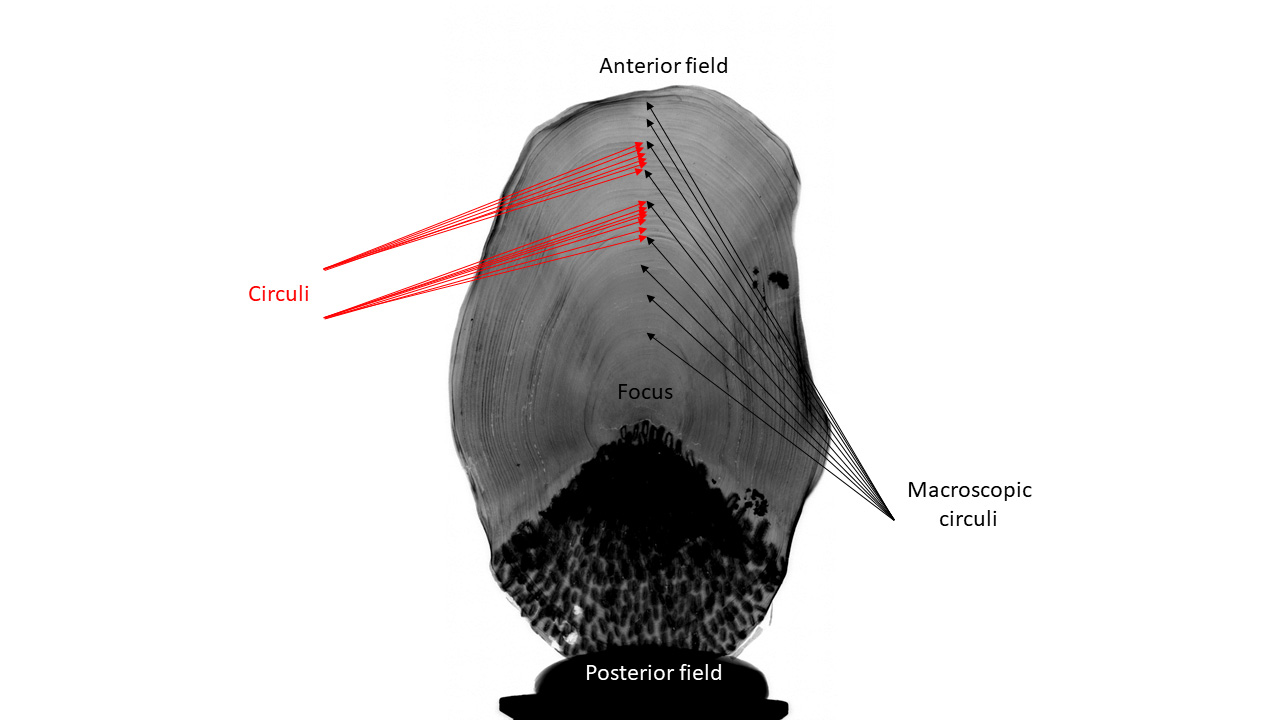

Researchers made the discovery by analyzing calcified growth structures, known as circuli, on the coelacanths' scales. Like tree rings, circuli act as a record of the fish's age. The circuli analysis also showed that coelacanths likely don't reach sexual maturity until age 55 and then gestate their offspring for a remarkably long time — five years in total.

"All told, the work reveals that the coelacanth is one of the slowest-growing and slowest-reproducing animals in the world," study lead researcher Kélig Mahé, of the Channel and North Sea Fisheries Research Unit at the National Institute for Ocean Science (IFREMER) in Boulogne-sur-mer, France, told Live Science in an email.

Related: See images of modern and fossil coelacanths

Lobe-finned coelacanths have been around since the Devonian period, about 400 million years ago. But researchers, who began finding coelacanth fossils in the 19th century, thought this ancient lineage had gone extinct about 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period, when an asteroid struck Earth and killed the nonavian dinosaurs. That perception changed in 1938, when an angler caught a living coelacanth off the coast of South Africa.

But these deep-sea fish have remained something of a mystery to scientists. For instance, the African coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) can grow to be 6.5 feet (2 meters) long and weigh up to 231 pounds (105 kilograms). Strangely, previous studies suggested that these fish grew to their huge sizes in just 20 years — a growth rate that placed coelacanths among the fastest-growing marine fish, comparable to tunas, the new study's researchers said. But coelacanths have a low metabolism and low fecundity, two factors usually not seen in species with fast growth rates, the researchers said.

Moreover, the two earlier studies had included the same 12 coelacanth specimens. In the new study, the researchers more than doubled that count, looking at 27 coelacanths captured near the Comoros, a group of islands roughly between Mozambique and Madagascar. These fish — which included 13 females, 11 males, one juvenile and two embryos — were captured between 1953 and 1991, and are now part of a collection at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While the previous studies relied on regular microscopes to look at circuli on the coelacanths' scales, the new team used polarized-light microscopes that "made it much easier to see contrast," Mahé said. "The technique revealed calcified structures on the scales so thin that they were very nearly imperceptible."

This method revealed that, of the 27 coelacanths, six were in their 60s and one was 84 years old. Contrary to the previous claims that these fish grew quickly, "all looked to have been growing very slowly," Mahé said.

To validate their numbers, the researchers double-checked that the circuli were laid down annually, and found that was the case, Mahé said. The team did this by documenting the last incremental circuli growth on each individual and comparing that with the month each fish was captured. By observing the monthly fluctuations of incremental growth throughout the year, they found that there was "only one scale growth peak during the year, which validates an annual periodicity," Mahé said.

Next, the researchers looked at the scales on the two embryos. Coelacanths are ovoviviparous, meaning their offspring develop inside eggs within the mother and then hatch as live young. Both embryos were 5 years old, the team found. This age jibes with the nearly 14-inch (35 centimeters) length of newly hatched coelacanths, suggesting that the fish gestate their young for half a decade, "contrary to the one to two years [of gestation] suggested by earlier studies," the researchers wrote in the study.

This finding makes the coelacanth one of the longest-gestating vertebrates — even longer than the deep-sea frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus), which has a three-year gestation, the researchers said.

Based on the known length of coelacanths at sexual maturity, the researchers "estimated the age of sexual maturity around 55 years old," Mahé added.

The team's growth model, as well as the discovery of the 84-year-old individual, suggests that these fish can hit the century mark, Mahé said.

The study was published online Thursday (June 17) in the journal Current Biology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus