Yosemite's glaciers have survived 20,000 years — but we could be the first people to see Sierra Nevada ice-free

New research finds the disappearance of glaciers in the Sierra Nevada will be unprecedented in the human history of North America.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The mountain glaciers of Yosemite National Park are projected to melt away in 75 years or less. Now, new research finds that their loss will be the first time humans have ever seen the Sierra Nevada mountains without ice.

According to a new study, published Wednesday (Oct. 1) in the journal Science Advances, the Sierra Nevada's glaciers have not disappeared since the last ice age. Because they reached their maximum extent during the ice age about 30,000 years ago, and because humans aren't thought to have arrived in North America until after 30,000 years ago, that means people have never witnessed an ice-free Sierra Nevada, according to the study.

"Anthropogenic climate change is therefore likely creating a no-analog scenario in the western United States within the current interglacial," the researchers wrote in the new paper.

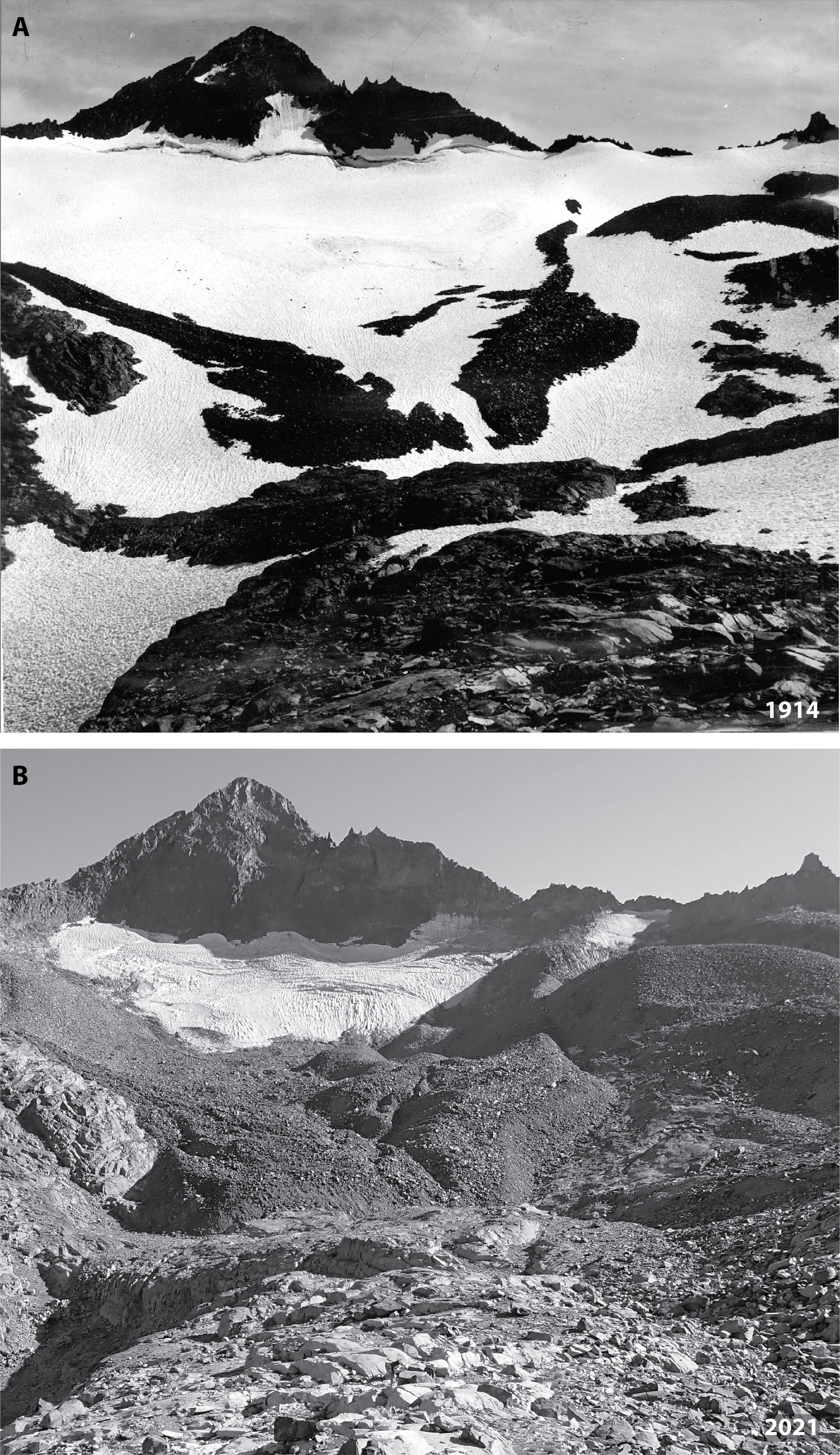

Geoscientists have long known that the extent of the mountain glaciers in what is now the western U.S. shrank and grew over the last 11,700 years, a timeframe known as the Holocene. In the warm early Holocene, the Sierra glaciers got smaller before expanding again in the mid-to-late Holocene. They've since shrunk in the last century, contracting from formidable ice walls hanging above steep slopes into small snowfields barely clinging to existence.

What was unclear was whether these glaciers ever fully disappeared. Some studies of glacial sediments in lakes below the ice suggest they may have vanished in the early Holocene, only to reform 3,000 years ago.

To get a clearer picture, the researchers tested samples of boulders and recently-exposed bedrock from near four retreating glaciers in and near Yosemite National Park: Conness, Maclure, Lyell and Palisade. They were looking for particular variations of carbon and the element beryllium that are formed only when cosmic rays from the sun hit the rock.

Since these variations don't form when the rocks are buried and sheltered from the sun, their presence can reveal when the rock was exposed. And because the variations decay away at known rates, they also provide a "clock" that gives a date for that exposure.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The results suggest that the rocks beneath these long-lasting glaciers have been exposed for between less than 100 to several thousand years, and that none of the glaciers have ever fully disappeared — though the eastern section of the Lyell glacier may have been even smaller than it was today during the early Holocene. This tracks with the current warming trends, the study authors wrote: California's recent summer warming of 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) over pre-industrial temperatures is comparable to or larger than the climate 11,000 years ago.

Prior to the Holocene, during the ice age — scientifically known as the Last Glacial Period — the Sierra Nevada glaciers would have been beefier, peaking around 30,000 years ago. Humans are confirmed to have been living in North America as early as 23,000 years ago. Some controversial archaeological evidence puts people in northwestern New Mexico around 30,000 years ago. Either way, it's unlikely that humans ever set eyes on an ice-free Sierra Nevada.

"[Our] reconstructed glacial history indicates that a future glacier-free Sierra Nevada is unprecedented in human history," the authors wrote.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus