25 things found frozen in Europe's mountain ice

Europe's glaciers and ice patches are an enormous deep freezer for artifacts. Here is a countdown of 25 of the most fascinating objects revealed by Europe's melting ice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Europe's glaciers and ice patches are a treasure-trove of ancient artifacts that show how civilizations and technology have changed over thousands of years.

"The archaeological finds from the ice are a tiny silver lining to global warming," archaeologist Lars Pilø, who heads the Secrets of the Ice project in the mountainous Oppland region of central Norway, told Live Science. 'The retreating ice has revealed itself to be an enormous deep freezer."

Here are 25 of the most fascinating objects revealed by Europe's melting ice.

1. Iron Age sandal

The discovery of a humble sandal, preserved in a mountain pass in central Norway, suggests that the area where it was found was a route for travelers about 1,700 years ago. This likely means that at the time the footwear was worn, there was less snow and ice there than there is now. Radiocarbon dating shows the sandal was made in about A.D. 300, and its style is similar to Roman sandals from that time.

2. Viking sword

This iron sword was found by hunters on a mountain slope in Norway, at more than 5,250 feet (1,600 meters) above sea level. There's no sign of a burial nearby and there’s seemingly no reason to have swords in such a location, so archaeologists think that its owner may have gotten lost.

3. Viking Age mitten

This left-handed mitten was found in the Lendbreen pass over the Lomseggen mountain ridge near the village of Lom in central Norway, which has been the site of many important finds. It was made from patches of several different textiles in about A.D. 900, during the Viking Age.

4. Medieval horseshoe

This horseshoe was also found at the Lendbreen pass and dates from about the 12th or 13th century. Researchers think it came from a packhorse, as horse dung and horse bones were discovered nearby. The date of the find, hundreds of years later than the sandal or mitten, suggests Lendbreen was used by travelers for hundreds of years. But the remote pass is almost never used today.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

5. Giant slingshots?

What seemed to be giant slingshots started melting out of the ice in 2011. Radiocarbon dating shows this one was made in about A.D. 400; it is over 3 feet (1 m) long, and has cuts made by a knife. Some are even larger. Archaeologists were bewildered by these objects until one of their team recognized them as “tång” or “pliers” for strapping down the load on sledges when transporting hay or leaves for animal fodder. Hay-sledges with tång were still in use in the area until the 1950s, when tractors became common.

6. Wooden peg

A few remote buildings once existed near Lendbreen, but none survive. This finely carved wooden peg was found in the timbers of an old farmhouse, possibly from the 19th century, but its purpose wasn't known until recently. "It is easy to think that our high mountains were remote and isolated regions in the past," Pilø said. "However, our finds show the ancient mountain people were well connected to the outside world. They sold products such as reindeer antler and pelts and imported commodities that they could not access locally, such as salt and grain."

7. Another wooden peg

Archaeologists later found another wooden peg of almost exactly the same design that had melted out of the Lendbreen ice patch. The purpose of these pegs was unknown, and this one was exhibited at a local museum, where an elderly woman finally solved the mystery: they were bits for kid goats or lambs to stop them suckling their mothers so that people could use the milk. She said she had used them in the 1930s; this one dates from the 11th century.

8. Medieval candle box

This wooden box sealed with a lid was found on the surface of the Lendbreen ice patch near the top of the pass. It was filled with a mysterious substance that turned out to be beeswax, and archaeologists think it once held a large candle. Candle boxes like these were used until recently in Norway to transport candles between summer and winter farm buildings. Radiocarbon dating shows this one is at least 500 years old.

9. Toy arrow

This 10-inch (26 centimeters) toy wooden arrow from about A.D. 600 offers a tantalizing glimpse into childhood at the time. "Was it lost in the snow during practice shooting? The unhappy child probably thought that it was lost forever," he said. But the ice preserved it for 1,400 years. Despite being a child's toy, it had a serious purpose, as hunting was a major source of food. "Mastering bow and arrow could be of life-or-death importance, not least during the time of this little arrow," Pilø said.

10. Real arrows

Reindeer were the main prey of hunters in the icy Norwegian mountains, and iron arrowheads like this one were found near the peak of the Sandgrovskaret mountain, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) northeast of Lendbreen. Archaeologists have seen an uptick in artifacts from the Late Antique Little Ice Age — a period from A.D. 536 to 660 when volcanic eruptions and dust clouds led to cooling global temperatures. "Our finds from the ice actually increase in number during this cold spell, probably because reindeer hunting became more important as agriculture struggled," Pilø said.

11. Iron Age hunting hide

These five arrowheads were found in a rock-built hunting shelter high on the Sandgrovskaret mountain, which was intended to make these Iron Age hunters "invisible" to their prey. Pilø said such hides were important because the primitive arrows were only deadly from about 66 feet (20 m) away, and reindeer are typically very shy of people.

12. Bronze Age bows, arrows and a lunchbox

The remains of two bows, arrows, and what seems to be a lunchbox from the Bronze Age were found in an Alpine pass in Switzerland. The artifacts were discovered at an altitude of almost 2,700 feet (8,800 m) beneath a rock shelter beside a glacier. They were likely left there by hunters or herders about 4,000 years ago. The ancient "lunchbox" is made from wood and once contained a roughly ground flour made from wheat, rye, barley and spelt.

13. Otzi the Iceman

One of the most famous discoveries that melted from Europe's mountain ice is the body and kit of Ötzi the Iceman, who died 5,300 years ago in an Alpine pass between modern-day Italy and Austria. Near Ötzi's remains, archaeologists found the remains of an ax with a copper blade, an unfinished bow, plant fiber, animal hides and pieces of leather. A severe wound from an arrowhead lodged in Ötzi's shoulder and a deep cut in his hand — thought to be a defensive injury — suggest he may have been ambushed.

14. Mummified couple

Ötzi is one of the oldest finds in the Alps, but relatively modern remains are also preserved in the ice. In 2017, the mummified bodies of a Swiss couple were found by a ski-lift technician near the Tsanfleuron glacier in the western Bernese Alps, after they'd been missing for 75 years. In August 1942, Marcelin and Francine Dumoulin had left their house in the mountain village of Chandolin to feed their cattle in a nearby pasture,but were never seen alive again. It's thought they fell into a crevasse on the glacier during bad weather.

15. WWII-era airplane

Glaciers can also preserve relatively modern objects — such as this aircraft from just after World War II, which was found by hikers in 2012. Archaeologists determined the wreck is a C-53 Skytrooper Dakota, an American military transport plane that crashed in bad weather in the Swiss Alps in 1946 after taking off from Vienna in Austria, bound for Pisa in Italy.

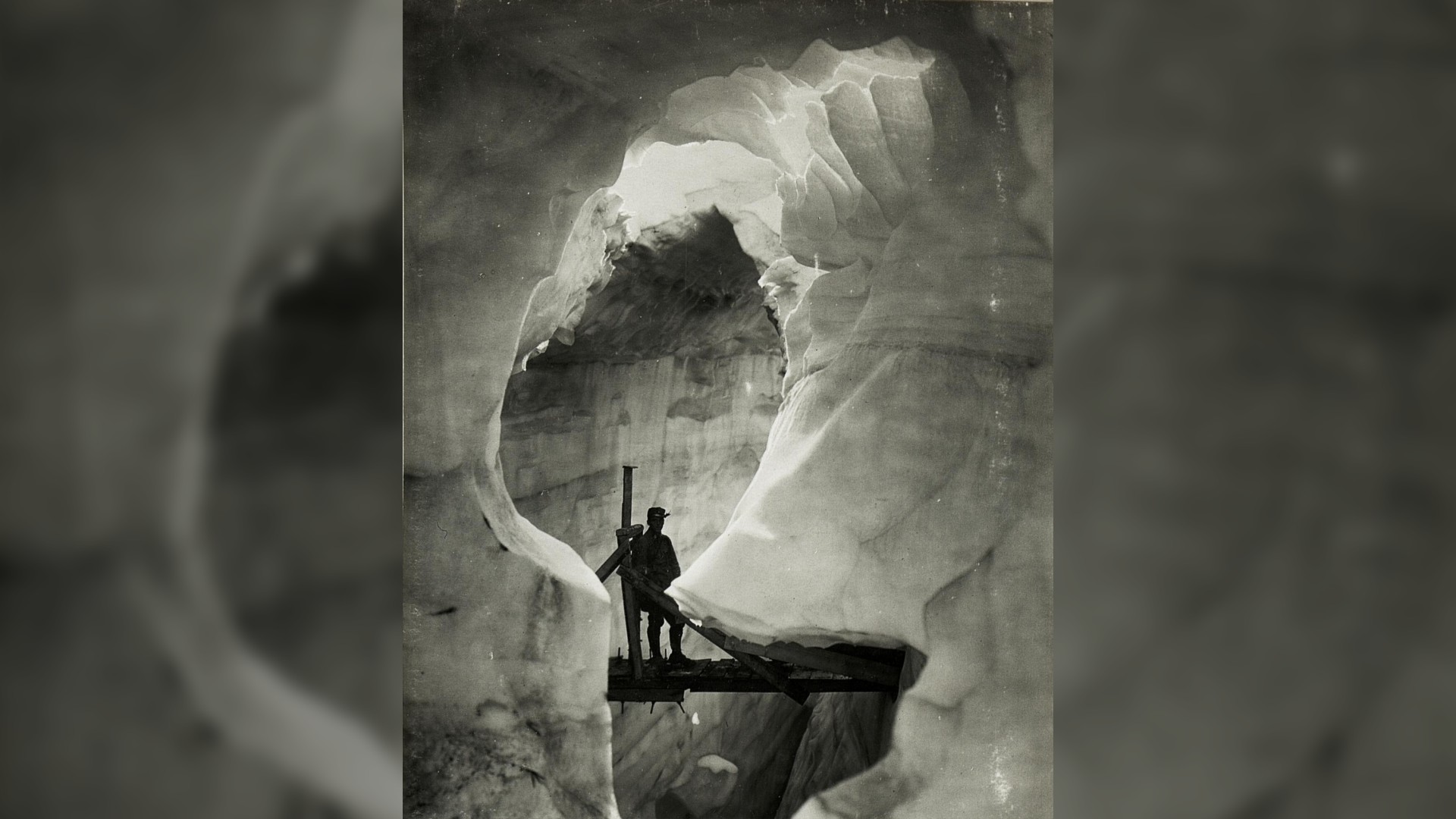

16. WWI battlefield

Relics of the earlier war litter the Alps between Italy and Austria where the Guerra Bianca — the "White War" — was fought between 1915 and 1918. The border between the Kingdom of Italy and the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time was high in the mountains, and combatants had to contend with freezing temperatures, ice and heavy snow. The remains of those killed in the fighting are still melting out of the glaciers in the region, along with artifacts like rifles, gas masks and glasses.

17. Bronze Age shell arrowheads

"With ice melting from anthropogenic climate change, these objects awaken from a long sleep and so does the history they carry," Pilø said. But the clock starts ticking once the artifacts are out in the open: "Exposure breaks down the artifacts and the sooner we can find them, the better it is," he said. These 3,500 year-old arrows have arrowheads made from the shells of freshwater mussels, probably from Norway's lowlands — something not seen anywhere else in the world. The Secrets of the Ice team have found three such arrows in ice in central Norway, and others from the same time period have also been found.

18. Pair of Iron Age skis

In 2014, the Secrets of the Ice team found a single Iron Age ski at the Digervarden ice patch in southern Norway's Reinheimen National Park — and they then found the other one a few meters away, but seven years later. They're made of wood, and both are remarkably well preserved, including the bindings that used to secure them to the skier's feet. "The new ski is even better preserved than the first one!" Pilø wrote in a blog post. "It is an unbelievable find."

19. Iron Age horse snowshoe

This snowshoe for a horse was found on Norway's Lendbreen ice patch in 2019. Its stunning preservation makes it seem as if it was lost recently, but radiocarbon dating shows it was made in the third century A.D. Archaeologists say this must have been at the beginning of the use of the Lendbreen Pass by travelers, and so the unlucky packhorse that lost its shoe was probably one of the first animals to cross the ice patch.

20. Norse sledge

The remains of a wooden sledge were found not far from the site where archaeologists uncovered the two Iron Age skis. It, too, likely dates from the late Iron Age, about 1300 years ago. "Finds of skis and sleds show that people traversed the high mountains even in the wintertime, with all the risks this involved," Pilø said.

21. Bronze Age bootie

"One of the most important lessons we have learned from the artifacts melting out of the ice is that humans used the high mountains much more intensively than previously thought," Pilø told Live Science. Dated to around 1100 B.C., this 3,000-year-old bootie is the oldest shoe ever found in Norway and one of the prized finds by the Secrets of the Ice team. The bootie is made from leather and probably belonged to a woman or a young man.

22. Iron Age tunic

This woven woolen tunic dates from about A.D. 300, during the late Iron Age and is the oldest complete piece of clothing ever found in Norway. It was discovered crumpled in a ball near the upper edge of the Lendbreen ice patch in 2011. It was heavily worn; patches show it was repaired several times, and the person who left it behind may not have been its first owner. The archaeologists at Secrets of the Ice think it was worn by a reindeer hunter who may have combined it with a waterproof outer layer.

23. Medieval walking stick

This 1,000-year-old walking stick found at Lendbreen is inscribed with runes that read "Owned by Joar," who hopefully made his way across the pass without it. "Glacial archaeological fieldwork can be quite challenging — it is very different from archaeology in the lowlands,' Pilø said. "There are a lot of logistics that need to be solved, such as tents, packhorses and food." What's more, the "weather can put a stop to all activities on short notice."

24. Viking spear

This iron spearhead and its wooden shaft were found on the Lendbreen ice patch in 1974; although the shaft had separated from the spearhead, the wood was so well preserved that the finder carried it down by hand. Analysis shows it dates from between A.D. 825 and 950, during the Viking Age. The wooden shaft was bent by the pressure of the snow when it was found, but the entire spear once measured over 7 feet (230 cm). The type of spearhead and the build-quality of the spear suggests it was a weapon for combat, rather than for hunting, and so it may have been lost in the pass by a Viking warrior on his travels; but archaeologists think it may also have been lost by a reindeer hunter.

25. Viking Age distaff

One of the most recent finds at Lendbreen is this ornately carved distaff — a device for holding wool while spinning it from fibers. It dates from the Viking Age, which was roughly from A.D. 800 until 1066. Household items like this are treasures for archaeologists, who can use them to reconstruct everyday lives and understand more about regional economies. But the artifacts are threatened. "Most of the ice in the high mountains in Scandinavia and the Alps is going to melt away this century, even with a rapid decline in greenhouse gas emissions," Pilø said. "The melt is already locked in. This is something that is hard to process, both intellectually and emotionally."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus