Climate change: Facts, news, features and articles about our warming planet

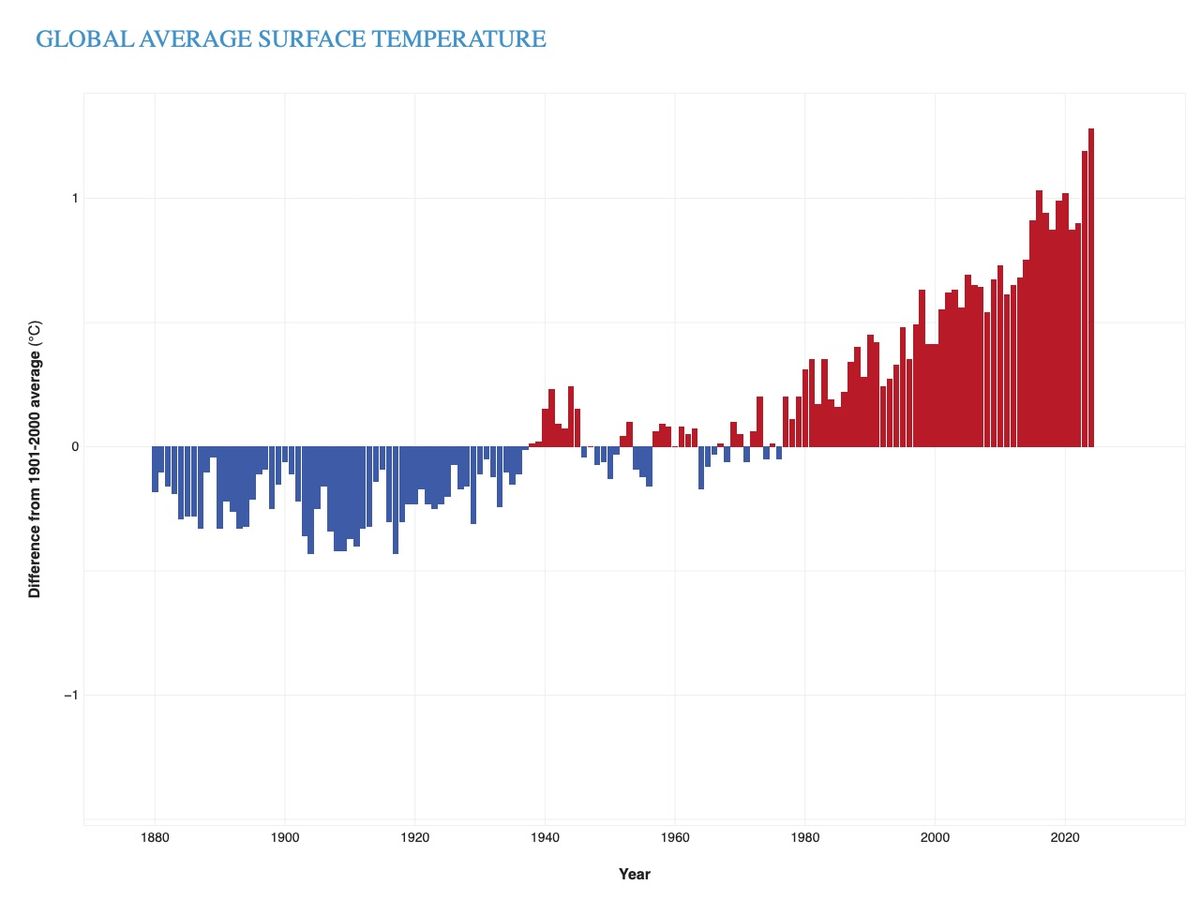

How much Earth has warmed since 1850: about 2 degrees Fahrenheit (1.1 degrees Celsius)

What causes climate change: Gases trapping heat in the atmosphere

The effects of a warming planet: Increased heat waves, flooding, wildfires, hurricanes and more

Climate change is any long-term shift in average weather patterns. Climate change has occurred many times in Earth's history, and for many different reasons. The changes in global temperature and weather patterns seen today, however, are caused by things humans do, like driving cars or burning coal. And today's climate change is happening much faster than natural climate variations that occurred in the past.

Scientists have many ways to track the climate over time. These methods have made it clear that today's climate change is linked to the emission of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane.

On average, greenhouse gases increase global temperatures. This is why climate change is sometimes called global warming. However, most researchers today prefer the term "climate change" because weather and climate vary around the globe, so even if the world is hotter overall, some regions may actually get colder. For example, warming global average temperatures might alter the flow of the jet stream, the major air current that affects the weather in North America. This could lead to periods of extreme cold in some areas.

5 fast facts about climate change

- Since 1982, Earth has warmed 0.36 F (0.20 C) every decade.

- About 3.6 billion people live in areas that make them highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

- Climate change could cost the world between $1.7 trillion and $3.1 trillion per year by 2050.

- Scientists say that if Earth warms by more than 3.6 F (2 C), there will be disastrous outcomes.

- Developing and low-income countries will be hit the hardest by climate change.

Everything you need to know about climate change

Is climate change real?

Scientists agree that climate change is real and caused by human activity. We can measure the effects of global warming because the climate of the past is recorded in ice, sediments, cave formations, coral reefs and even tree rings. Researchers can look at chemical signals — such as the CO2 trapped inside glaciers — to determine what atmospheric conditions were like in the past. They can study microscopic fossilized pollen to learn what vegetation used to thrive in any given area. Scientists can also measure tree rings to get a season-by-season record of temperature and moisture. Sediments in the ocean can even provide a window into what the climate was like millions of years ago.

Humans started keeping their own detailed records of the climate during the industrial revolution, a period of rapid technological advancement beginning in the late 18th century. Measures of things like land temperature began to improve in the late 1800s, and ship captains started keeping a wealth of ocean-based weather data in their logs. The development of satellite technology in the 1970s provided an explosion of data, including how much ice there is at the poles, the temperatures at the ocean's surface, and cloud coverage.

All in all, these records show that Earth's global average temperature has increased by about 1.8 F (1 C) since the industrial revolution. Climate change has sped up in the past few decades, with the planet warming about 0.36 F (0.2 C) every 10 years.

What causes climate change?

Climate change is caused by greenhouse gases trapping heat in Earth's atmosphere. Greenhouse gases include CO2, methane and nitrous oxide. They are called greenhouse gases because they trap heat from the sun's rays near Earth's surface, much like the glass walls of a greenhouse keep heat inside. Small changes in the amounts of greenhouse gases in the air can add up to major changes on a global scale.

The burning of fossil fuels — such as coal, oil and natural gas — is the biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions. Livestock, like cows and sheep, are also a source of greenhouse gases. Plants help scrub greenhouse gases from the air, so when people cut down trees across a large area, greenhouse gas emissions rise.

Before the industrial revolution, there were about 280 CO2 molecules for every million molecules in the atmosphere, or 280 parts per million (ppm). As of 2021, the global average level of CO2 was 419 ppm — more than 100 ppm higher than the level has been in the past 800,000 years. Carbon is also building up in the atmosphere faster than in the past. The heat-trapping ability of all that extra carbon has translated to rising global average temperatures. And the world is getting hotter, faster: Two-thirds of the warming that's taken place since 1880 has occurred since 1975.

What are the effects of climate change?

Climate change is creating a warmer world with rising sea levels and more dangerous weather. It is also messing up ecosystems around the world.

Some of the most dramatic changes can be seen in the Arctic, where sea ice is melting. Even the oldest sea ice, which usually sticks around year after year, is getting thinner. Global sea ice levels hit a low in 2025, and scientists now think we could see the first summer with no ice in the Arctic sometime between 2040 and 2060.

Melting ice has already caused seas to rise. The global average sea level has risen by 8 to 9 inches (21 to 24 centimeters) since 1880. For coastal areas of the U.S., this sea level rise has resulted in three to nine times more flooding when tides are high.

Climate change is affecting the oceans, too. Ocean water absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere, which creates a chemical reaction that causes ocean acidification. Ocean surface waters have become 30% more acidic since the beginning of the industrial revolution. When water is too acidic, corals can't build their carbonate skeletons, and shelled animals — such as clams and some types of plankton — can die.

Climate change is even affecting when spring weather appears. Spring is arriving earlier in the United States. Climate models now suggest that early springs could be the norm by 2050. But late freezes will likely still occur, creating conditions in which plants could sprout leaves early in the season and then be damaged by cold temperatures.

Droughts and wildfires will also likely become more common. Extreme wildfires have more than doubled worldwide, and fire seasons are getting longer and more intense. Climate models predict that droughts will become more frequent and last longer.

Can we stop climate change?

Humans have already triggered major changes to Earth's climate, but it's still possible to avoid some of the worst effects of climate change. To do that, we would need to slash greenhouse gas emissions.

If all human greenhouse gas emissions stopped immediately, Earth would likely continue to warm, because CO2 remains in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. Some scientists have proposed a system called carbon capture and storage — a method that removes CO2 from the atmosphere — to fix this issue. Carbon capture and storage may be possible, but it's so expensive that it's currently unlikely to happen.

Even if we could remove the carbon that's already in the atmosphere, preventing future warming requires humans to stop spewing greenhouse gases now. Slowing climate change is a collective effort that will require collaboration among countries, states and cities, as well as major adjustments to the way the world operates. The most ambitious effort to stop global warming so far is the Paris Agreement. This international treaty between 195 countries aims to keep warming below 3.6 F (2 C). So far, however, most countries are not meeting the goals they set for themselves. The U.S. withdrew from the Paris Agreement in 2025, when Donald Trump began his second term as president.

Climate change pictures

Wildfires

Climate change is causing wildfire season to become longer and more intense.

Melting glaciers

Glaciers, such as this one in Iceland, are melting, which is contributing to sea level rise.

Rising sea levels

Rising sea levels, a major consequence of climate change, are already affecting Tierra Bomba Island, Colombia.

Extreme weather

Climate change is making extreme weather events such as hurricanes, flooding and heat waves more common.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Marilyn Perkins is the former content manager at Live Science. She is a science writer and illustrator based in Los Angeles, California. She received her master’s degree in science writing from Johns Hopkins and her bachelor's degree in neuroscience from Pomona College. Her work has been featured in publications including New Scientist, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health magazine and Penn Today, and she was the recipient of the 2024 National Association of Science Writers Excellence in Institutional Writing Award, short-form category.

Discover more about climate change

A cold blob of water in the North Atlantic is an ominous sign that a system of currents that regulate the planet's climate could be weakening.

From shrinking goats to a dimmer Earth, here are some of the lesser-known impacts of rising global temperatures.

Climate change will fundamentally challenge the world's urban centers. Three cities — San Diego, Milan and Jakarta — offer lessons for how to adapt to a warming planet.

Latest about Climate change

California's wildfire season is shifting, with more blazes after the traditional high-risk window, study finds

By Stephanie Pappas published

New research finds that climate-driven shifts in wildfire seasons in North America are different depending on the ecosystem.

'The warming trend nearly doubled after 2014': The rate of global warming has accelerated more in the past decade than ever before

By Pragathi Ravi published

A new analysis finds that global warming has significantly accelerated since 2015, but not everyone agrees.

Planting trees in the sea could act as a huge carbon sink and save millions of dollars in storm damage every year. What is stopping us from doing it?

By Sarah Wild published

A new study reveals restoring mangroves could save $800 million in storm damage, protect 140,000 people from flooding, and remove almost triple the amount of CO2 produced by cars in the U.S. every year.

'Humans can't be considered to be separate from the environment': Award-winning scientist Meha Jain on using satellites and real world experiences to help farmers in India facing a precarious future

By Pragathi Ravi published

INTERVIEW Agriculture in India is under threat from extreme weather events linked to climate change. We speak to Meha Jain, an associate professor of geospatial data sciences, food systems at the University of Michigan, who has spent nearly 20 years working with farmers in India to understand the threats they are facing and how they are adapting.

Trump is bringing car pollution and other greenhouse gases back to America's skies. Here are the health risks we all face from climate change.

By Jonathan Levy, Howard Frumkin, Jonathan Patz, Vijay Limaye published

Four researchers dive into the health risks associated with climate change, and why the recent decision by the Trump administration to rescind key environmental policies could lead to serious harm.

'It's telling us there's something big going on': Unprecedented spike in atmospheric methane during the COVID-19 pandemic has a troubling explanation

By Victoria Atkinson published

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the atmosphere temporarily lost its ability to break down methane, leading to a huge spike in the greenhouse gas.

China's emissions are flatlining — and may be falling — in critical turning point for biggest emitter, report says

By Ben Turner published

The carbon emissions of the world's biggest greenhouse gas emitter have plateaued for nearly two years.

Californians have been using far less water than suppliers estimated — what does this mean for the state?

By Chris Simms published

Flawed assumptions about water demand mean suppliers in California overestimated future demand by an average of 74% over 20 years — positive news for the drought-embattled state.

'The scientific cost would be severe': A Trump Greenland takeover would put climate research at risk

By Martin Siegert published

Trump's calls for a takeover of Greenland puts open scientific collaboration that is helping our understanding of the threat of global sea-level rise at risk.

Amazon rainforest is transitioning to a 'hypertropical' climate — and trees won't survive that for long

By Sascha Pare published

The Amazon rainforest currently has a few days or weeks of hot drought conditions per year, but researchers say this could increase to 150 days per year by 2100.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus