New map of methane 'super-emitters' shows some of the largest methane clouds ever seen

A NASA instrument designed to study dust has revealed that some of the largest methane clouds ever seen are floating over the US, Iran and elsewhere.

Some of the largest clouds of heat-trapping methane gas ever detected are currently floating over New Mexico, Iran and several other "super-emitter" hot spots around the world, according to a new NASA report.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas that contributes to the warming of the atmosphere. Although it's less abundant than carbon dioxide (CO2), methane can trap 80 times more heat pound-for-pound than CO2, according to NASA. Human activities like the fossil fuel, natural gas, agriculture and waste industries contribute methane to the atmosphere, and understanding where the methane emission hot spots are can help scientists better understand humanity's impact on the warming climate.

NASA's Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation (EMIT), which was installed on the International Space Station in July to help scientists understand how dust affects climate change, managed to detect methane plumes as well.

EMIT detected more than 50 methane "super-emitters," or facilities and infrastructure that emit methane at high rates. These super-emitters occur all over the world, from the Southwest United States to Central Asia and the Middle East.

Related: There's so much methane in this Arctic lake that you can light the air on fire

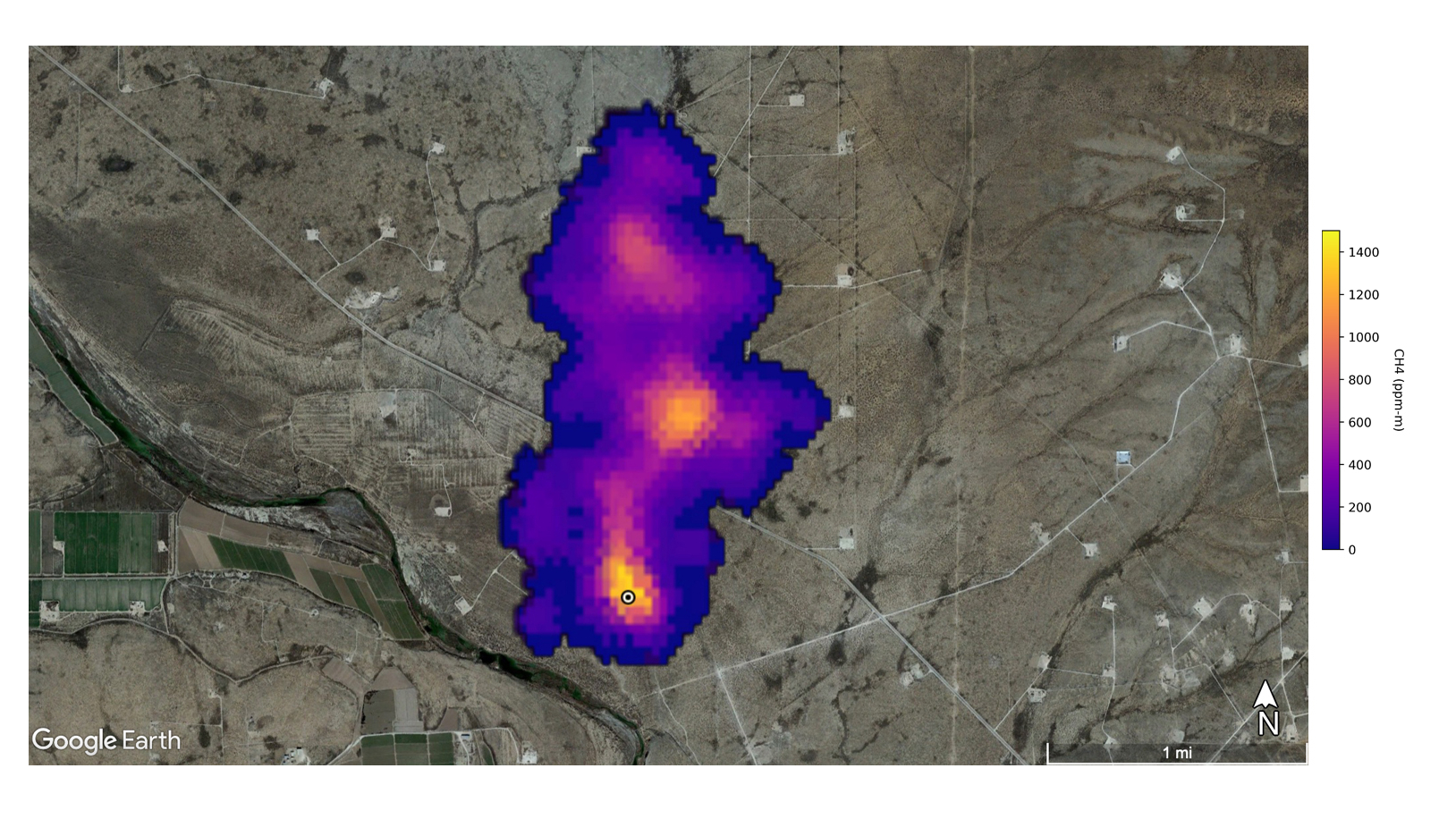

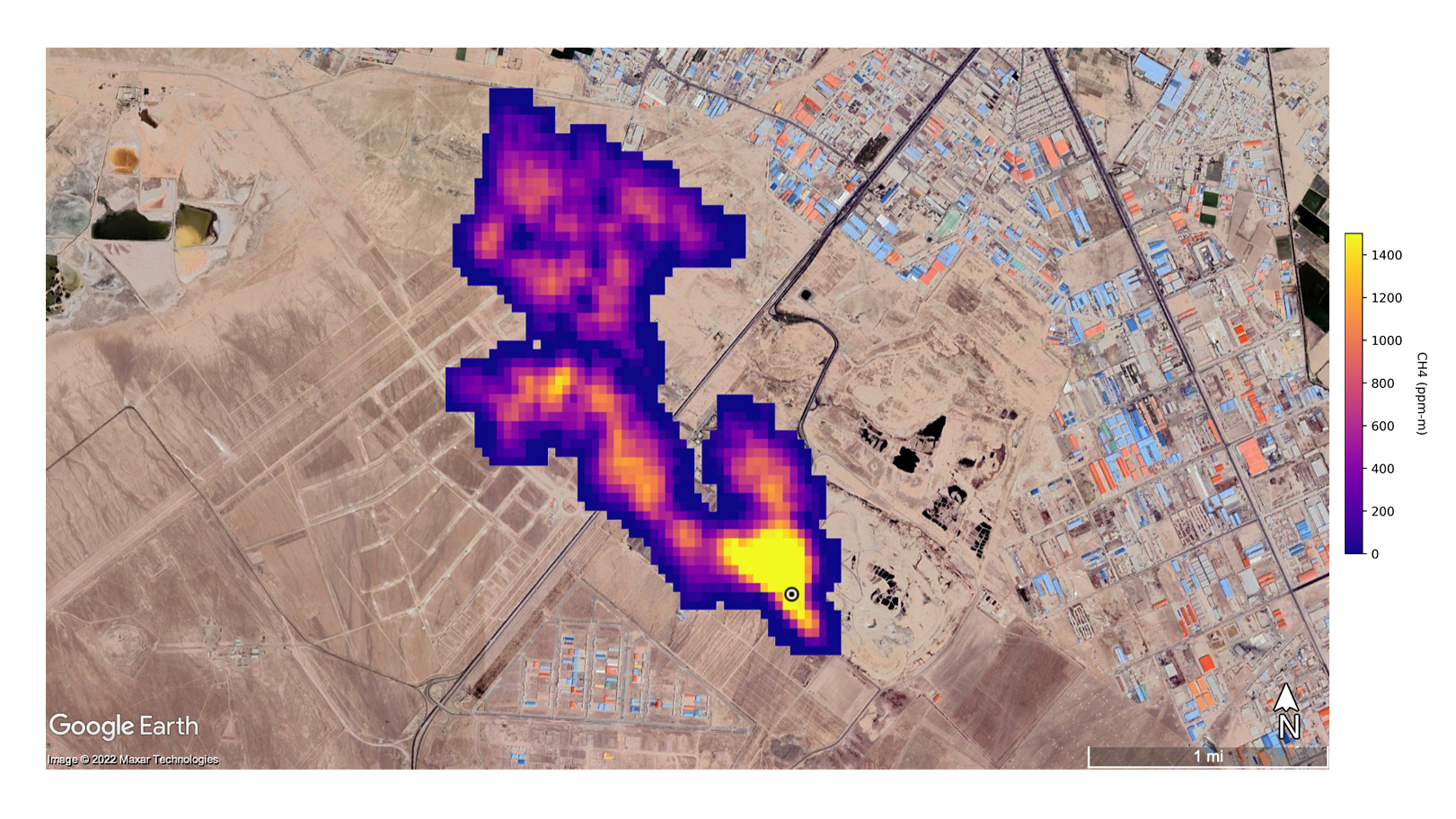

The super-emitters spotted by EMIT include an oil field in New Mexico, southeast of Carlsbad; oil and gas infrastructure in Turkmenistan east of the Caspian Sea port city of Hazar; and a waste processing complex south of Iran's capital Tehran.

Methane plumes from these sources ranged from 2 miles (3.3 kilometers) to 20 miles (32 km) wide, and researchers estimate that these three sources together emit around 170,000 pounds (77,110 kilograms) of methane per hour.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Some of the plumes EMIT detected are among the largest ever seen — unlike anything that has ever been observed from space," Andrew Thorpe, a scientist leading the EMIT methane research at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in a NASA statement. "What we've found in just a short time already exceeds our expectations."

EMIT was originally designed to help researchers understand another atmospheric phenomenon that affects climate — dust that is swept around the globe from Earth's largest deserts. The minerals that make up the dust can trap or reflect heat, depending on their chemical makeup, and until now, there wasn't an instrument capable of producing high-resolution data about these minerals.

EMIT identifies different minerals through spectroscopy, or analyzing the light that the minerals reflect. Each mineral reflects light in a slightly different way, allowing EMIT to identify each mineral like a fingerprint. Because methane also absorbs infrared light in a unique way, EMIT can detect it.

The team expects that the instrument could detect hundreds more methane hotspots around the world, allowing scientists to better understand where Earth's methane comes from. Methane doesn't last as long as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere — the heat-trapping gas lasts just decades versus CO2's centuries-long-lifetime — and climate experts say that reducing methane emissions could have a much more immediate effect (relatively) on slowing climate warming.

"We have been eager to see how EMIT's mineral data will improve climate modeling," Kate Calvin, NASA's chief scientist and senior climate advisor, said in the statement. "This additional methane-detecting capability offers a remarkable opportunity to measure and monitor greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change."

JoAnna Wendel is a freelance science writer living in Portland, Oregon. She mainly covers Earth and planetary science but also loves the ocean, invertebrates, lichen and moss. JoAnna's work has appeared in Eos, Smithsonian Magazine, Knowable Magazine, Popular Science and more. JoAnna is also a science cartoonist and has published comics with Gizmodo, NASA, Science News for Students and more. She graduated from the University of Oregon with a degree in general sciences because she couldn't decide on her favorite area of science. In her spare time, JoAnna likes to hike, read, paint, do crossword puzzles and hang out with her cat, Pancake.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus