Are there any mythological creatures that haven't been debunked?

Bigfoot isn't the most credible bipedal-ape myth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

From modern hikers spotting tall apes sauntering through deep forests to medieval sailors spying menacing leviathans swirling beneath their ships, fantastical tales of unknown beasts have fascinated us for generations.

These ambiguous animals are often thought of as nothing more than stories, but are there any mythological creatures that haven't been debunked? The short answer is, yes, sort of.

For the purpose of this mystery, we looked at the real-life potential of undiscovered creatures from myths. That rules out some cryptids — creatures rumored to exist — that are known to science but have been declared extinct, such as Tasmanian tigers (Thylacinus cynocephalus).

Debunking isn't easy; you have to expose a falseness or sham, according to Merriam-Webster. Creatures of myth are not necessarily a sham just because they don't exist exactly as described, and proving with 100% certainty that any creature doesn't exist is almost impossible, because we can't look everywhere at once.

Related: Are ghosts real?

Mythological creatures are often said to be restricted to a specific location or range. For example, the Loch Ness Monster in Scotland is supposed to live in its namesake home, Loch Ness. This allows scientists to use what they know about the loch to make a reasonable assessment as to whether it's inhabited by a mythical beast.

Loch Ness is an oligotrophic loch, which means it's low in nutrients and unlikely to support a large unknown predator species at the top of the food chain, Charles Paxton, a statistical and aquatic ecologist at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, told Live Science. "If there's a Loch Ness Monster, there's very few of them," he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When Paxton researches the Loch Ness Monster and other legendary creatures, he focuses on the available evidence, rather than looking for the creatures themselves. Based on what he's seen, he doesn't think the Loch Ness Monster exists.

"The question then for me as a scientist is, what could explain the misreported phenomena?" Paxton said. "It could be explained by some aspect of human psychology, it could be explained by a misperception of known species or it could be explained by an unknown species."

Scientists haven't documented all the species on Earth, not by a long shot. A 2013 study published in the journal Science estimated that we've discovered about 1.5 million living species out of around 5 million, give or take 3 million. However, that could be considered a conservative estimate. A 2011 paper published in the journal PLOS Biology predicted that there are about 8.7 million species alive today, and a 2016 study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimated that there are more than a trillion microbial species alone.

As far as aquatic animals go, Paxton thinks we've exhausted big unknown animals close to the surface, apart from potentially some undiscovered beaked whales — scarcely seen deep-diving whale species that can hold their breath for over 3 hours. In other words, almost all of the large animals that humans could have seen in the water to inspire myths are known.

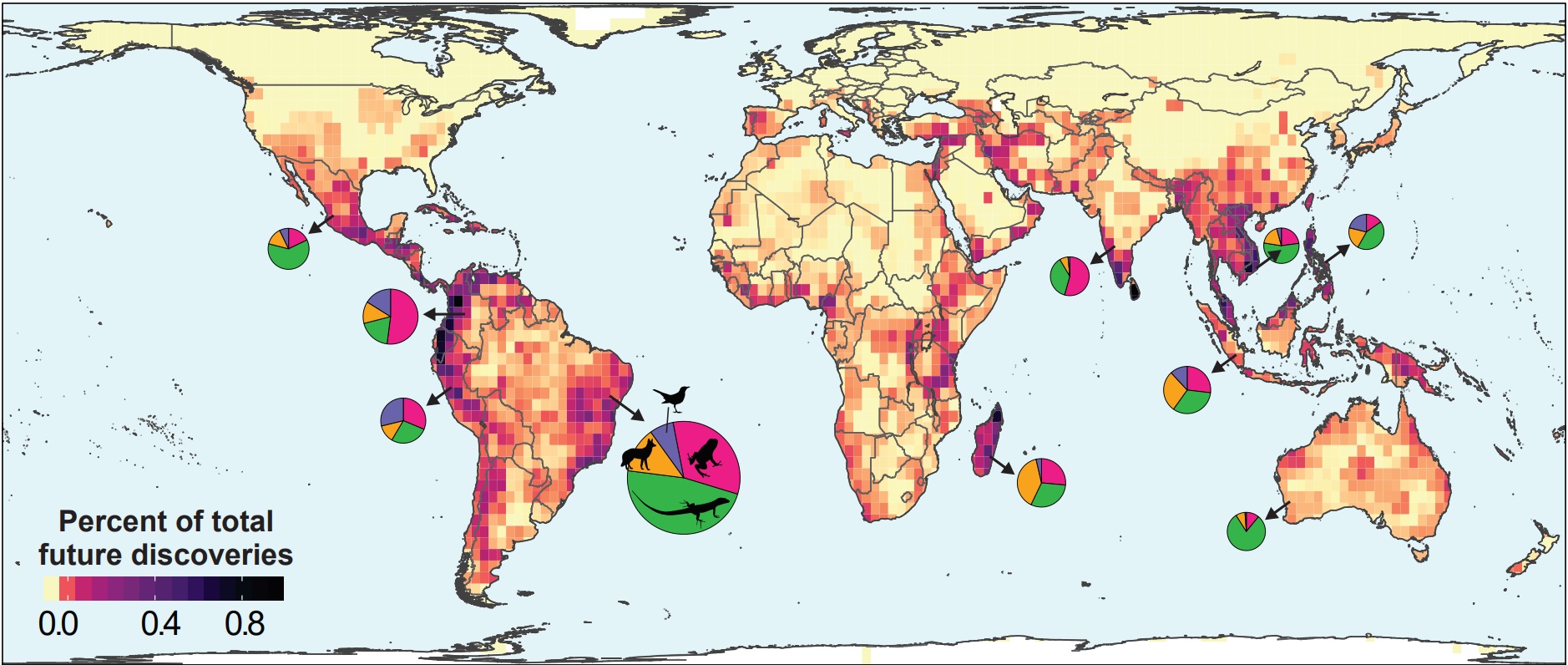

A 2021 study published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution investigated the potential for undiscovered animals on land. "The chances of being discovered and described, they are not equal among species," lead author Mario Moura, an ecology professor at the Federal University of Paraíba in Brazil, told Live Science.

Large animals living in or near areas populated by humans are far less likely to slip through the scientific net compared with smaller animals living in remote habitats that are difficult to access, such as tropical rainforests. According to the study, reptiles are the least-explored group of animals with the highest potential for new species to be discovered across the world.

Related: Are there any giant animals humans haven't discovered yet?

Dragons are the most famous mythological reptilians, but scholars link their legendary ability to breathe fire to medieval depictions of the mouth of hell, often presented as a monster's mouth, and there's scant physical evidence for real dragons.

Dragons, like many mythological creatures, do have parallels in nature. Fossil remains of dinosaurs and other extinct animals have helped bolster dragon stories. For example, the skull of the now-extinct woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) from the Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) was kept in the Austrian city of Klagenfurt as a skull of a "dragon," said to have been killed before the city was founded around 1250, according to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

The Map of Life website has an interactive map of Moura's 2021 study findings where you can search the globe for potential unknown animals. The map exposes the U.S. as largely a tapped well for new animals, having been extensively studied and having less species diversity than the tropics. However, eagle-eyed viewers may notice that two of the states with the best potential for undiscovered mammals are Washington and Oregon — prime Bigfoot country.

Bigfoot tales describe a giant, ape-like creature that is most often "sighted" in the Pacific Northwest. However, Moura noted that there's only a very small increased chance of mammals in this region; most likely, these alleged sightings are driven by the presence of something "hard to find," such as rodents, shrews or bats, and not a massive hairy ape.

While it doesn't look great for Bigfoot, that doesn't mean there aren't any undiscovered primates in the world. Moura said he thinks the best chances for large undiscovered animals are likely in the primate family, with species such as Plecturocebus parecis, a titi monkey from Brazil, discovered in recent decades.

The researchers identified four potential hotspots for undiscovered life: Brazil, Indonesia, Madagascar and Colombia. These countries are rich in species and have not been thoroughly studied by researchers yet. "The task is bigger, and the hands are fewer," Moura said.

There are many stories of large, mysterious primates in folklore, but perhaps the most promising is said to live in Indonesia. A legendary creature called Orang Pendek is a bipedal ape rumored to roam the Indonesian island of Sumatra, with sightings reported by local people, guides, settlers and Western researchers.

Orang Pendek, which means "short person" in Indonesian, has the best chance of discovery out of all the mystery primates, according to "The Field Guide to Bigfoot and Other Mystery Primates" (Anomalist Books, 2006). Co-author Loren Coleman, founder and director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Maine, told Live Science in an email that Orang Pendek "will be hard to find" but is the creature he would most like to search for if he had unlimited funds.

Related: Which animals have the longest arms?

Sumatra is already home to orangutans, a known group of great apes. These reddish primates live in trees, and their range in northern Sumatra doesn't appear to overlap with where Orang Pendek is supposed to live in central Sumatra.

"It seems where orangutans occur, there's virtually no stories about them [Orang Pendek]," Serge Wich, a professor of primate biology at Liverpool John Moores University in England who's surveyed orangutans in Sumatra, told Live Science. "It's only where they don't occur."

Wich suggested that maybe the Orang Pendek stories are about orangutans that used to live farther south before their range was restricted to the north. He said he finds it "remarkable" that nobody has found Orang Pendek if it exists, given the forests said to house them have been monitored with camera traps. "This, to me, indicates that they're probably not there," he said.

One person who's certain Orang Pendek is, or at least was, out there is Jeremy Holden, a freelance wildlife photographer. He claims to have seen the creature with his own eyes on Sumatra in October 1994.

Holden told Live Science his encounter took place just inside a forest within Kerinci Seblat National Park, where people had reported seeing Orang Pendek. "The animal passed probably about 7 meters [23 feet] from me," Holden said. "It was walking bipedally. Its head was turned away from me as if it was listening to probably my guide behind."

Holden said the "formidable creature" was about 5 feet (1.5 m) tall, powerfully built and covered in hair the yellowish color of "dead grass." While Holden had a camera around his neck, he said he didn't take a photo because he didn't want the creature to hear the camera click and see him.

"I kept quiet because there was a whole host of emotions going through my mind at the time, but one of them was actually fear," he said. The animal closest to what he saw is a gibbon, which can be the same color, but he said he certainly didn't confuse it with a gibbon, which are smaller.

Holden was a tourist during the 1994 encounter. In 1995, he began searching for evidence of Orang Pendek on a three-year research project funded by Fauna & Flora International (FFI), a U.K.-based conservation charity.

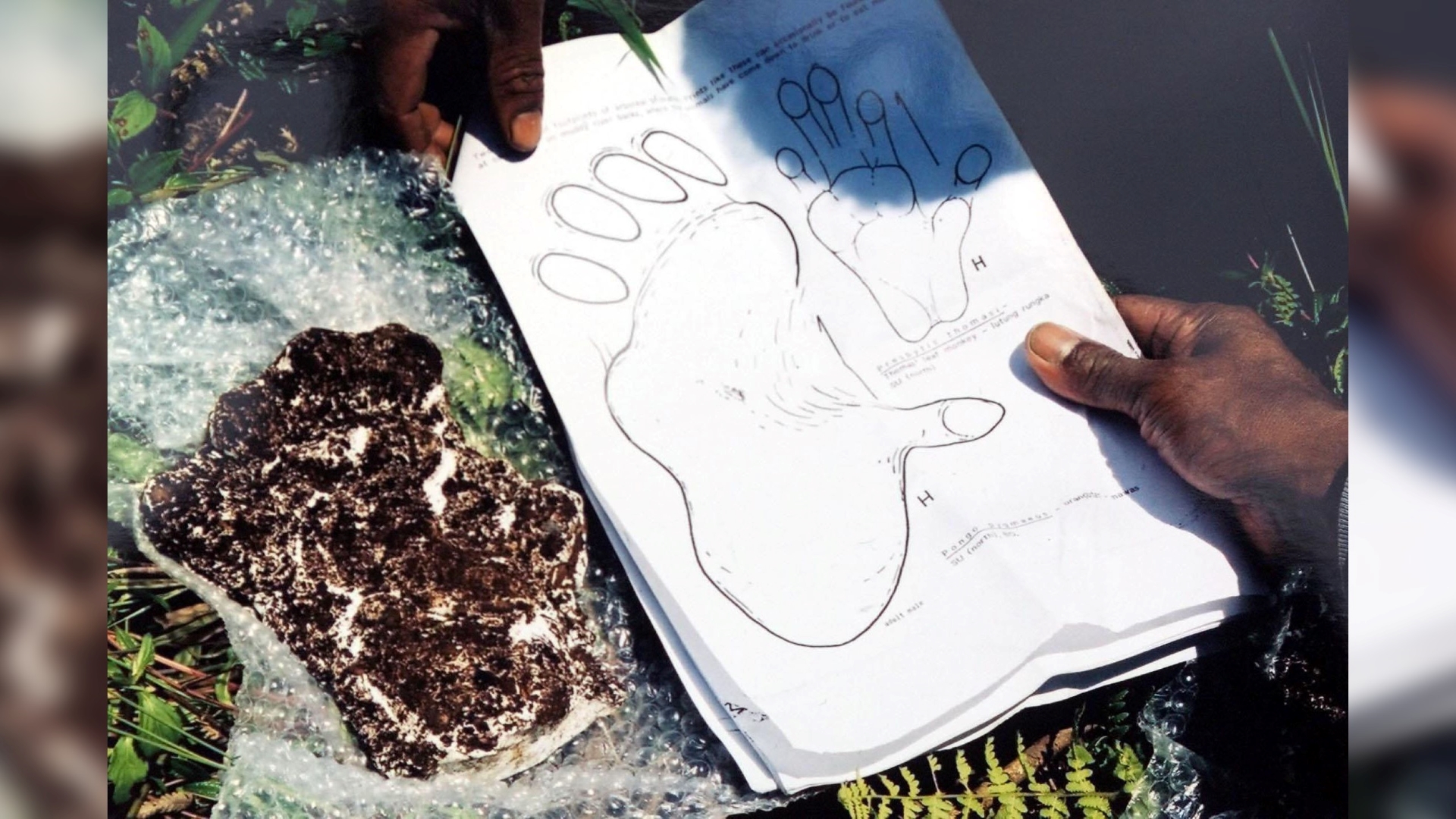

He teamed up with conservationist Deborah Martyr, who also claims to have seen Orang Pendek, to document eyewitness accounts and attempt to photograph the creature using camera traps. According to the book "With Honourable Intent: A Natural History of Fauna & Flora International" (William Collins, 2017), "The project failed to obtain conclusive proof other than several footprint casts that appear not to match any known primate species."

Related: What's the first species humans drove to extinction?

National Geographic funded a separate Orang Pendek project between 2005 and 2009. This project also used camera traps and didn't get a shot of the creature. Alex Schlegel, who worked on the project and is now an artificial intelligence researcher in the Bay Area, is unsure whether Orang Pendek exists.

"I would say that it's going to be as bizarre or more bizarre for it not to exist than for it to exist," Schlegel told the Strange Phenomenon podcast in 2020. "As hard as it might be to believe that something like this exists and lives still and has not been documented by Western science in the Sumatran rainforest, my experience has been that I would be as or more shocked if it ended up being nothing other than stories."

Holden said he has continued looking for Orang Pandek on and off since the FFI research project ended. Although he's failed to photograph Orang Pendek, he has found species that were previously unknown to science, including Nepenthes holdenii, a carnivorous plant in Cambodia that is named after him, according to FFI. He's also led camera trapping teams that photographed new species for the first time, including primates.

In fact, Holden has successfully snapped so many animals that aren't Orang Pendek that he thinks all of his work to find the creature can be viewed as proof that it doesn't exist, even though he still believes it does.

Holden pointed to the Sumatran ground cuckoo (Carpococcyx viridis) as his justification for why the Orang Pendek could have escaped documentation all these years. The critically endangered ground-dwelling cuckoo went more than 90 years without being seen until an individual was trapped in 1997, according to the Zoological Society of London's EDGE of Existence website.

"It took me from 1995 when I started camera trapping until 2015 to get my first photograph of a Sumatran ground cuckoo," Holden said. "So these things happen. But anybody that doesn't believe me, I can sympathize, because I've got nothing more to show than a story."

Originally published on Live Science.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus